Just look around.

Sit-ins and occupations. Marches, rallies, and protests. People demanding the release of video showing an unarmed teen being killed by a police officer. A national #StudentBlackOut on hundreds of campuses presenting administrators with student-created racial equality demands. On Harvard's campus, portraits of black law professors were vandalized. Politicians and public leaders have been accused of secret Ku Kux Klan membership. And a nationally televised benefit concert brought celebrities together to fight the epidemic of racism, commit to peace, and stand with the communities that have been devastated by hate crimes, mass shootings, and police brutality.

And all of that was just in the past two weeks.

Photo by Christopher Polk/Getty Images for A+E Networks.

What's happening all around us doesn't just sound like a movement. It actually sounds kind of ... like a movie.

You've probably seen this type of movie before and know it well: the classic "fight the power" tale. One where a charismatic leader or group of downtrodden but strong and brave "everyday people" rise up to take a stand against the powers that be. "Norma Rae." "Selma." "Mandela." "The Shawshank Redemption." "Les Misérables." Even "The Hunger Games." We all have our fave.

And when we watch those films, most of us pick sides, standing and cheering in solidarity with the "good guys."

Image from "Les Misérables" by movieCax/Flickr.

So, why does it seem like so many people — people who love those movies — can't see that we're all living in an epic blockbuster resistance movie right now?

Why isn't everyone tingling with excitement, cheering the slogans, joining organizations, and loudly standing on the "right side" of history?

Why doesn't everyone see that from University of Missouri's campus to Yale's, from the protests in Ferguson and Baltimore to the "die-ins" in Miami and Chicago, there is a real-life history-making movement happening, demanding equality, justice, and an end to every -ism that remains hidden in plain sight?

Why do some people refuse to recognize that today's Black Lives Matter movement and all of its connected struggles — the DREAMers working on immigration reform and the Fight-for-15ers fighting for a living wage — are the civil rights movement of today?

Why don't they recognize that today's Kendrick Lamars and John Legends are yesterday's Aretha Franklins and Marvin Gayes, creating a bold, unapologetic soundtrack for change?

And why don't they see the leaders of today, brilliant activists and strategists like Patrisse Cullors, Linda Sarsour, Carmen Perez, DeRay McKesson, Tiq Milan, Tamika Mallory, Rashad Robinson, Alida Garcia, and Nettaa, in all their femaleness and malesness and queerness and multi-faithness and multi-racialness, as the Dr. Kings and John Lewises and Ella Bakers that they really are?

Photo of Linda Sarsour, Carmen Perez, and Tamika Mallory. Used with permission from NYJusticeLeague.

The simple answer is, of course, because life is a bit more complicated than the average movie.

See, in the movies, the story is straightforward. It's easy to tell up from down and right from wrong. Thanks to adept writers and our position in the audience as external observers, we are able to see all parties and perspectives clearly.

We know who The Leader is. It's our main character, our underdog. And the supporters are The Good Guys.

We know who The Villain is. He's probably embodied by one individual, and that person is nothing like us. The villain is a caricature whose values are so despicable that any respectable person today would outright reject them.

We know the story formula too. We know the turning points in the plot, when the breakthroughs happen. We know that the heroes will hit their lowest moment and everything will seem lost, but the crescendo of music followed by a dramatic speech signals the confrontation. These things tell us that this is aMoment to Remember, after which nothing will ever be the same. And goodness will win.

If only real life were so simple.

Scene from "Selma" via BagoGames/Flickr.

In real life, the characters don't have good guy/bad guy labels. Roles aren't clearly defined. Villains can be complicated abstract systems of power rather than scowling individuals, while heroes don't announce their presence with sweeping shots of the city and a helpful title card.

Most importantly, in real life, there is no audience with an external gaze. We cannot step outside of our lives to see the part of the long arc toward justice we're living in. We can only see where we are in the moment. Standing here in present day, it's hard to see the future history books as history is being made all around us.

In the movies, we have the luxury of hindsight. We know exactly what the demands were. A writer can look back at the tangled messiness that was a 10-15-year movement and simplify its far-reaching, ever-evolving goals and demands. They will be conveniently uttered by one character in a pivotal moment. A montage would probably flash across the screen with a simple unifying goal around which the entire plot revolves.

In real life, there are numerous goals and multiple strategies. There is give and take and dissent. Movements are multi-organismic, with many parts and strains. Just because you cannot always google "tell me what today's civil rights movement wants" does not mean that there aren't brilliant, politically savvy people all over the country organizing and fighting for clear outcomes at every level — county, city, state, and federal.

But perhaps the deepest, most intimate reason we don't always recognize revolution in real time is that in the movies, social upheaval confronts, challenges, and breaks up a world that is usually foreign to us as an audience, one that we can distance ourselves from (think Panem in "The Hunger Games"). We see the contours of a harsh, immoral, unjust system clearly because we do not see it as our system. It is a system of the past (or a faraway future) and we have no tangible attachment to it. As a result, it's disruption costs us nothing.

Photo by Kevork Djansezian/Getty Images.

In real life, on the other hand, revolution disrupts the world we live in right now — a world that, while not perfect, many have learned to navigate and build a life in.

The imperfect systems that exist are the systems that many good people have found a way to survive in and, in some cases, benefit from. And those same people who might cheer for the factory to be shut down, or the police chief fired, or the king overthrown, while watching a movie, might not want to pay the inconvenient cost of disruption when it happens at their child's school or to their brother-in-law the officer or on the streets outside their door.

There are, of course, those who denigrate today's movement because they are desperately clinging to values of hatred and fear. Those may really think and behave like villains.

Others, though, embrace willful obliviousness simply because it is too scary to challenge the system that pays their bills or keeps them employed or makes them feel some semblance of safety and security, even when it clearly doesn't for so many others.

But there is one more group: Those who just don't believe that what they are seeing today, with its tweets and hoodies, is as serious as the movements of yesteryear.

To them I offer this simple truth:

Revolution never looks like what we think it will.

Not only does it not look like the movement that came before it, the kicker is that oftentimes what you might think radical change should look like — a new president, perhaps — with all of its pomp and circumstance, doesn't even come close to the type of revolution that movies are made of.

What does, though, is the kind of uncomfortable, unapologetic, persistentaction and organizing in the three years since Trayvon Martin was killed, led by everyone from kids in hoodies, to athletes, to gay men and trans women, to bold young writers like Darnelle Moore and Dr. Brittany Cooper, to students drowning in debt, to people who shut down highways and who shout down presidential candidates to get their voices heard.

Photo by Jessica McGowan/Getty Images.

Just like in the movies, people really are being killed while corrupt leaders get richer and more powerful. People are putting their lives on the line and making themselves vulnerable while hate speech still flourishes and is defended in the name of "free speech."

And just like in the movies, young people, black, brown, white, gay, and straight, descendants of slaves and immigrants and hippies alike, are working together to create a new, more just reality for themselves and future generations.

In the words of activist Shaun King:

"If you EVER wondered who you would be or what you would do if you lived during the Civil Rights Movement, stop. You are living in that time, RIGHT NOW."

Photo by Jessica McGowan/Getty Images.

So here's my question to you: When the movie based on this moment in history gets made decades from now, what character will you be?

The character passing a bowl of potatoes over dinner, shaking your head at the "unruly activists" as peaceful protesters march outside your door?

The one sitting in a high-rise corner office drinking a latte, bemoaning the youth's "lack of strategy and smarts" as victories are being won day-by-day on campuses and in state houses?

Or maybe the one in the pew on Sunday morning praying for peace and order while holy righteous battles are being won in the streets outside the church's doors?

Not me.

I want to be on the right side of history. I want to be on the side of messy disruption wherever it may be found.

I want to show the movie to my future kids 20 years from now and proudly point and say, "That was mommy, my love. And she was one of the good guys."

Christopher Plummer and Julie Andrews on location in Salzburg, 1964

Christopher Plummer and Julie Andrews on location in Salzburg, 1964 Car Drifting GIF

Car Drifting GIF Bed Bugs Belarus GIF

Bed Bugs Belarus GIF Bed bugs are about the size of an apple seed.

Bed bugs are about the size of an apple seed. bug GIF

bug GIF Checking mattresses for signs of bed bugs at a hotel can help you avoid bringing them home.

Checking mattresses for signs of bed bugs at a hotel can help you avoid bringing them home.

A person holds a plate with bulletsImages via Canva

A person holds a plate with bulletsImages via Canva A horse making a funny faceImage via Canva

A horse making a funny faceImage via Canva A baby with glasses sleeping on a moon pillowImage via Canva

A baby with glasses sleeping on a moon pillowImage via Canva Ocean Seafood GIF by Lorraine Nam

Ocean Seafood GIF by Lorraine Nam Giga Pudding Snack GIF

Giga Pudding Snack GIF

A young boy blows a whistle Image via Canva

A young boy blows a whistle Image via Canva Two women laugh looking at a laptop screenImage via Canva

Two women laugh looking at a laptop screenImage via Canva

Two women at a gym push an oversized envelopeImages via Canva

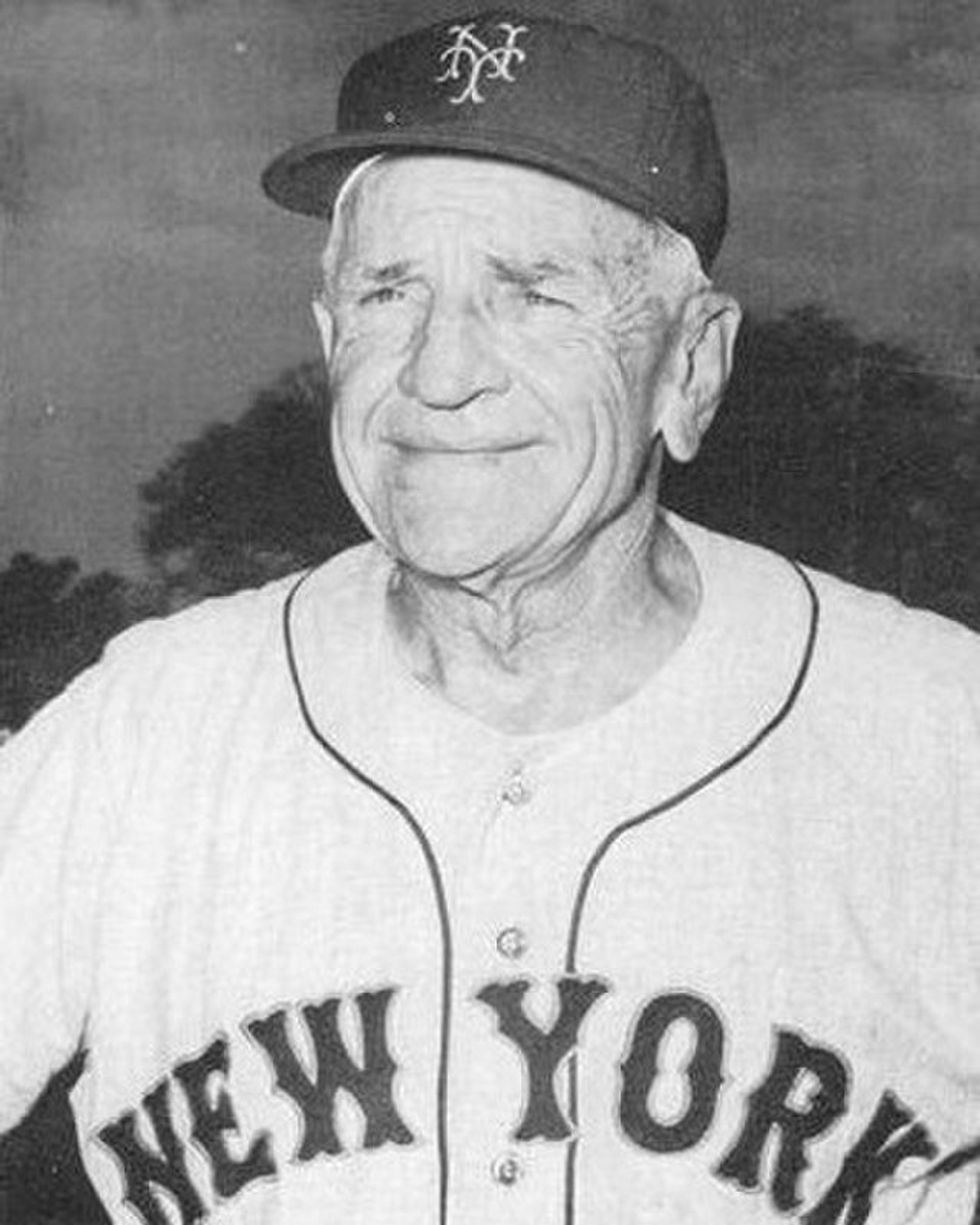

Two women at a gym push an oversized envelopeImages via Canva Casey Stengel served as inspiration for the Miracle Max character in "The Princess Bride."Public Domain

Casey Stengel served as inspiration for the Miracle Max character in "The Princess Bride."Public Domain