Why LGBTQ people are leaving places like New York and San Francisco for red-state cities.

When Cleve Jones was growing up, he felt different from everyone else.

Living as a gay teenager in Phoenix, Arizona, in the early 1970s was difficult to say the least. His dad, a psychologist, believed that homosexuality was something to be cured. His classmates in gym class bullied him so much, he pretended to have a chronic lung ailment so that he could stay in the library instead of the gym. And at one point, he said, he felt so alone that he considered suicide.

Human rights activist and author of "When We Rise" Cleve Jones in 2009. Photo by Kristian Dowling/Getty Images.

Jones has been a civil rights activist for over 40 years, and he is depicted as one of the main characters in ABC's miniseries "When We Rise."

His experience as a teenager was similar to that of many LGBTQ people at that time. The American Psychiatric Association considered homosexuality an "illness" until 1973, and throughout the 1950s and '60s, members of the LGBTQ community risked psychiatric lockup or jail if they were "discovered." They could also be fired from their jobs or lose custody of their children. Bullying and violence was also a common threat they faced.

In the show, Jones' character reads about the burgeoning gay liberation movement in Life magazine and is inspired to seek out the movement. Jones recalls that moment vividly from his own life.

Cleve sees the 1971 Life magazine with an article about the gay liberation movement in the ABC miniseries "When We Rise." Screenshot used with permission.

"This magazine, in a matter of minutes, revealed to me that there were other people like me," Jones said in an NPR interview. "There was a community, and there were places we could live safely. And one of those places was called San Francisco."

So, Jones hitchhiked from Arizona to San Francisco in 1973 to start his new life.

Cleve leaves his family behind in Phoenix to move to San Francisco in the ABC miniseries "When We Rise." Screenshot used with permission.

Many LGBTQ people who moved out of red states to cities in blue states in the '60s and '70s helped shape those cities into the same-sex safe havens that we know them to be today.

Cities like San Francisco and New York were seen as places where the LGBTQ community could go to live as themselves and escape some of the oppression, discrimination, and violence they faced back home.

The 1979 Gay Freedom Day Parade and Celebration in front of San Francisco City Hall, which marked the 10th anniversary of the gay rights movement. Photo by Paul Sakuma/AP Photo.

Starting with the Stonewall Riots in 1969, the burgeoning gay rights movement grew inside the cities in places such as the Castro district of San Francisco. There, groups mobilized and spearheaded the fight for their rights over the next several decades.

By 1990, the LGBTQ population was largely concentrated in coastal safe-haven cities, including Seattle, Atlanta, Boston, Washington, D.C., and, of course, New York and San Francisco.

The 46th annual Gay Pride March on June 26, 2016, in New York City. Photo by Bryan R. Smith/AFP/Getty Images.

Today, that trend may be reversing; members of the LGBTQ community are actually leaving those places and moving to smaller, redder cities.

Consumer Affairs analyzed U.S. Census data and Gallup polling information and found that by 2014, large LGBTQ populations had cropped up in red-state cities, including Salt Lake City, Louisville, Norfolk, and Indianapolis. For example, in 1990, only 1% of the Salt Lake City population identified as LGBTQ, but by 2014, that number had grown to 5% — making it the seventh largest LGBTQ urban population in the country.

Economics plays a large role in the trend; the cost to live in many safe-haven cities has skyrocketed. For example, the cost of living in New York City rose by 23% in just five years between 2009 and 2014 while in San Francisco, the median rent price was nearing $4,500 by 2016.

Meanwhile, numerous smaller cities in red states, including Salt Lake City and Indianapolis, offer shorter commutes, cheaper rent, and less competition for the good-paying jobs.

A pride flag flies in front of the Historic Mormon Temple as part of an LGBTQ protest in Salt Lake City, Utah. Photo by George Frey/Getty Images.

Progress on LGBTQ issues across the country is another reason for the exodus.

There have been a number of federal actions over the last 15 years to solidify equal rights,including President Barack Obama’s executive order protecting LGBTQ federal workers from discrimination and federal and Supreme Court actions that effectively legalized same-sex marriage across a number of red states, including Arizona, Utah, and Indiana. Several cities have also passed local laws protecting the LGBTQ community, including housing and employment protections and benefits for domestic partners of city employees.

A mother to two lesbian daughters holds a sign while watching the Gay Pride Parade on June 28, 2015, in New York City. Photo by Yana Paskova/Getty Images.

Of course, there's a long way to go — many cities are hotbeds for legal challenges to LGBTQ rights, and 28 states in the U.S. still lack LGBTQ employment discrimination protections.

Rick Scot moved from West Hollywood and bought a house in a suburb of North Carolina with his husband because of cost. But North Carolina is also the birthplace of a controversial law — House Bill 2 — that prevents cities from enacting their own anti-discrimination laws and restricted transgender bathroom access statewide. The law has yet to be successfully repealed.

"I have friends and colleagues who won’t come here," Scot told the L.A. Times.

For some in the LGBTQ community, living in a red state also offers the opportunity to be involved in bringing about real change at a local level.

Protesters in City Creek Park in Salt Lake City in 2015. Photo by George Frey/Getty Images.

New York City and San Francisco didn’t become gay-friendly cities overnight. Change was gradual and hard-fought — and it happened largely because the activists who lived there demanded it.

That's why in the ABC limited series “When We Rise,” Cleve Jones decides to stay put and fight for gay rights in San Francisco rather than go off to Europe to find a better home with his friend.

Roma and Cleve in the ABC miniseries, "When We Rise." Screenshot used with permission.

And today, LGBTQ activists have the opportunity to drive change in red-state cities that have less friendly laws. Some activists are even calling these cities "the new frontier."

That is why Tyler Curry, who calls himself a "blue-ribbon homosexual in a bright red state," has chosen to stay and live Texas — so that he can help bring about change for everyone. "People’s minds can be changed and victories can be won in each state government, no matter how difficult it may seem," Curry wrote in an editorial on the Advocate. "Twenty years ago, the state and federal rights that we now have were merely pipe dreams, but our community refused to let hate beat out hope."

He continued, "Today, we still need to be steadfast in our commitment to LGBT rights across the country, and that means staying put in our red states and demanding respect."

Watch the full trailer for ABC's "When We Rise," which begins Feb. 27 at 9 p.m. Eastern/8 p.m. Central:

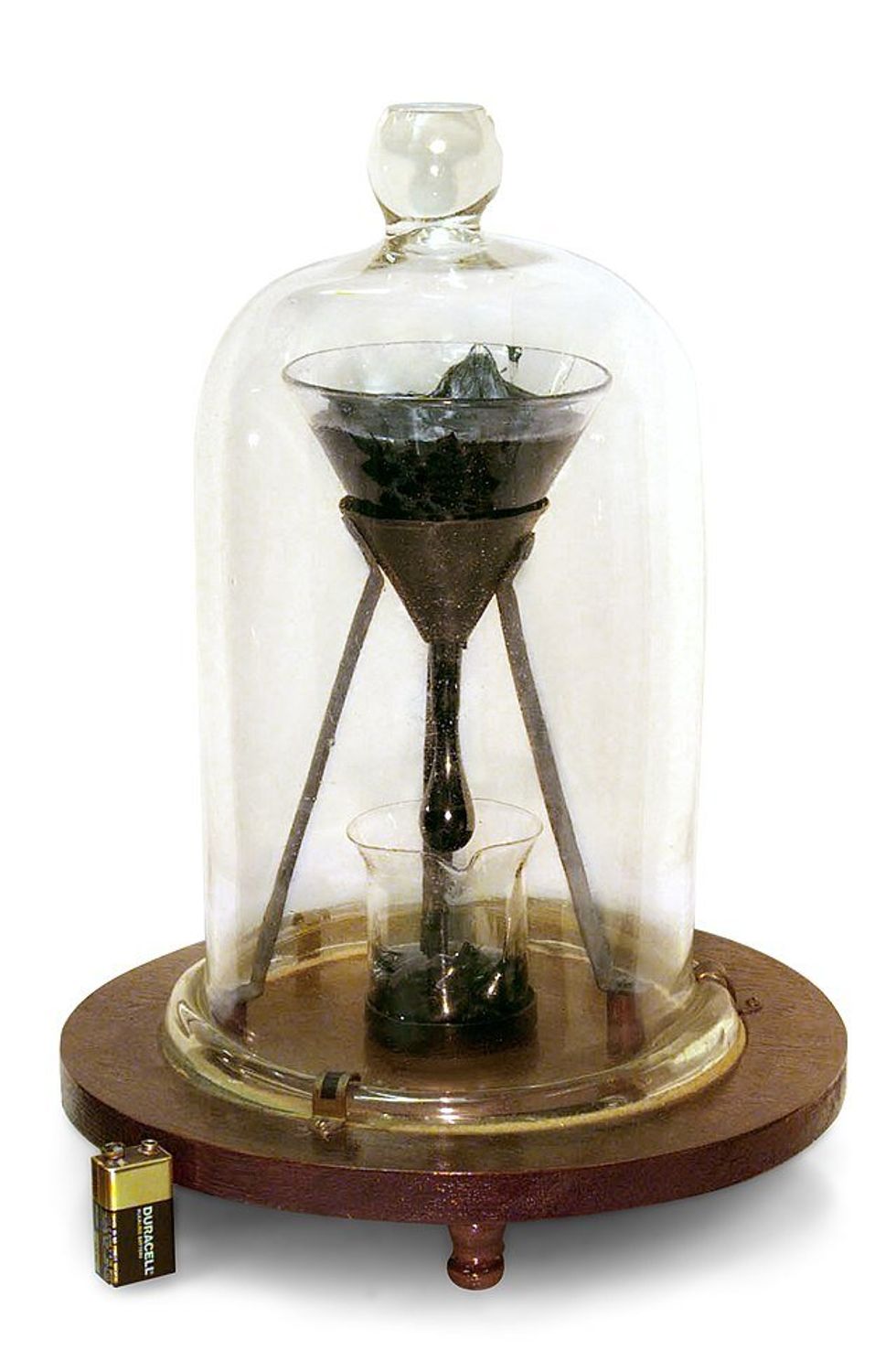

Pitch moves so slowly it can't be seen to be moving with the naked eye until it prepares to drop. Battery for size reference.

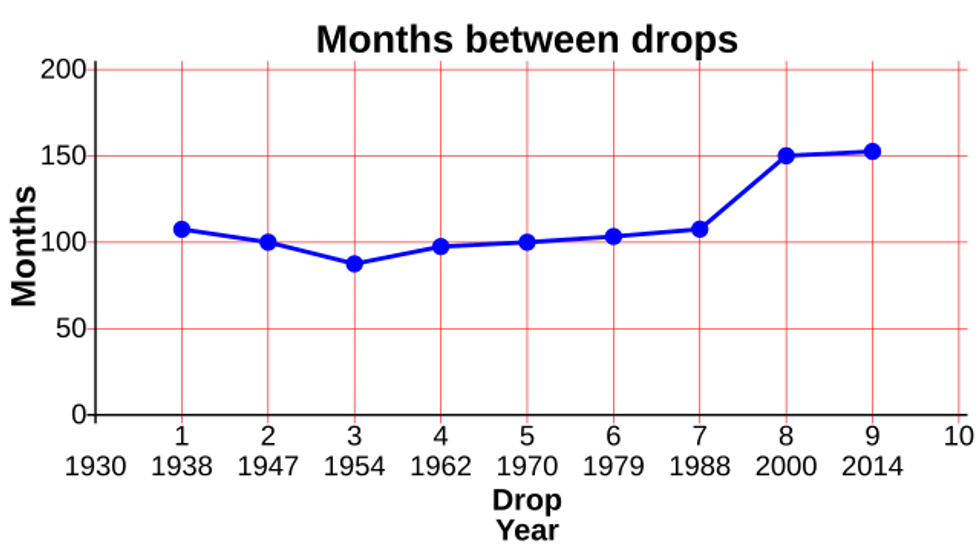

Pitch moves so slowly it can't be seen to be moving with the naked eye until it prepares to drop. Battery for size reference. The first seven drops fell around 8 years apart. Then the building got air conditioning and the intervals changed to around 13 years.

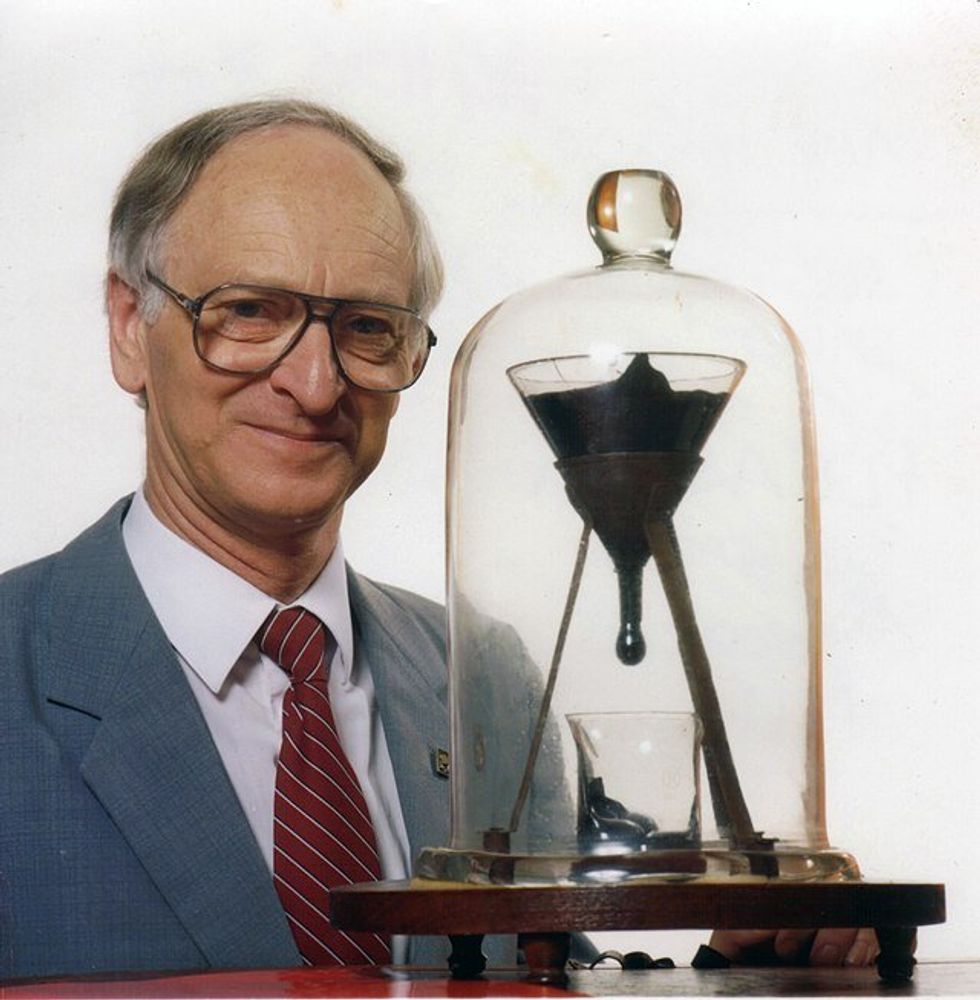

The first seven drops fell around 8 years apart. Then the building got air conditioning and the intervals changed to around 13 years. John Mainstone, the second custodian of the Pitch Drop Experiment, with the funnel in 1990.

John Mainstone, the second custodian of the Pitch Drop Experiment, with the funnel in 1990. Who wouldn't want to recreate this?

Who wouldn't want to recreate this? A father does his daughter's hair

A father does his daughter's hair A father plays chess with his daughter

A father plays chess with his daughter A dad hula hoops with his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad hula hoops with his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. A dad talks to his daughter while working at his deskAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad talks to his daughter while working at his deskAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. A dad performs a puppet show for his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad performs a puppet show for his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. A dad walks with his daughter on his backAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad walks with his daughter on his backAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. a dad carries a suitcase that his daughter holds onto

a dad carries a suitcase that his daughter holds onto A dad holds his sleeping daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad holds his sleeping daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. A superhero dad looks over his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A superhero dad looks over his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. A dad takes the small corner of the bed with his dauthterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad takes the small corner of the bed with his dauthterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. Being regular guests haas helped make us good Airbnb hosts.

Being regular guests haas helped make us good Airbnb hosts. Chasing Tom And Jerry GIF by Max

Chasing Tom And Jerry GIF by Max Asking guests to stip the sheets saves almost no time and costs a lot in goodwill.

Asking guests to stip the sheets saves almost no time and costs a lot in goodwill. Most guests are try to leave the place as they found it, standard cleaning routine aside.

Most guests are try to leave the place as they found it, standard cleaning routine aside.  A happily married couple.via

A happily married couple.via  A couple getting married.via

A couple getting married.via  Kingboiza asks men about marriage.

Kingboiza asks men about marriage.