I am visiting my family when my hearing cuts out.

It’s scary to abruptly lose one of your senses. Everything sounds muffled, like the people speaking around me are behind a closed door at the end of a long hallway, distant and unreachable. The pain in my ears is sharp.

I feel my breath shallow and quicken, anxiety beating its hummingbird wings in my ribcage. First, because something is so clearly wrong. And second, because I will have to go to the doctor, and I am fat.

As I walk into the office, I steel myself for the charm offensive I’ll need to wage.

As a fat person, my health is always suspect, and never more than when I step into an unknown doctor’s office.

Image via iStock.

The nurse and I chat away as she takes my vital signs, though I still strain to hear her. As we speak, she takes my blood pressure once, then frowns. She takes it again, then another look. She excuses herself and comes back with another cuff, trying a third time. Nervous, I ask her what the problem is.

“I’m just not getting a good read,” she says, adjusting the second cuff.

“Is everything OK?”

“It’s coming back great, but that can’t be right. Overweight patients don’t have good blood pressure.”

It’s a familiar moment that I’ve come to dread. Even with her trusted equipment, even with the numbers clear as day in front of her, she cannot see that I am healthy. She anticipates poor health, and anything better becomes invisible.

I have entrusted her with my health, and she cannot see it.

Eventually, the doctor enters. Both of my ears are infected, and I’m prescribed antibiotics.

He gives me detailed instructions on how to use the eardrops and advises me to take all of the medicine as prescribed. As the visit wraps up, I ask the doctor if there’s anything else I should do for aftercare.

“You should lose some weight.”

This moment is familiar, too. It leaves me disappointed and unsurprised. When I seek medical care, many providers only seem to see my weight. Whatever the diagnosis, weight loss is its prescribed treatment. I explain what I eat, how much I exercise, my history of low blood pressure, and general good health. It only rarely influences my course of treatment. Because the biggest predictor of my health, even in the eyes of professionals, is my dress size. I have proven myself an irresponsible owner of my own body. Every detail I provide is suspect.

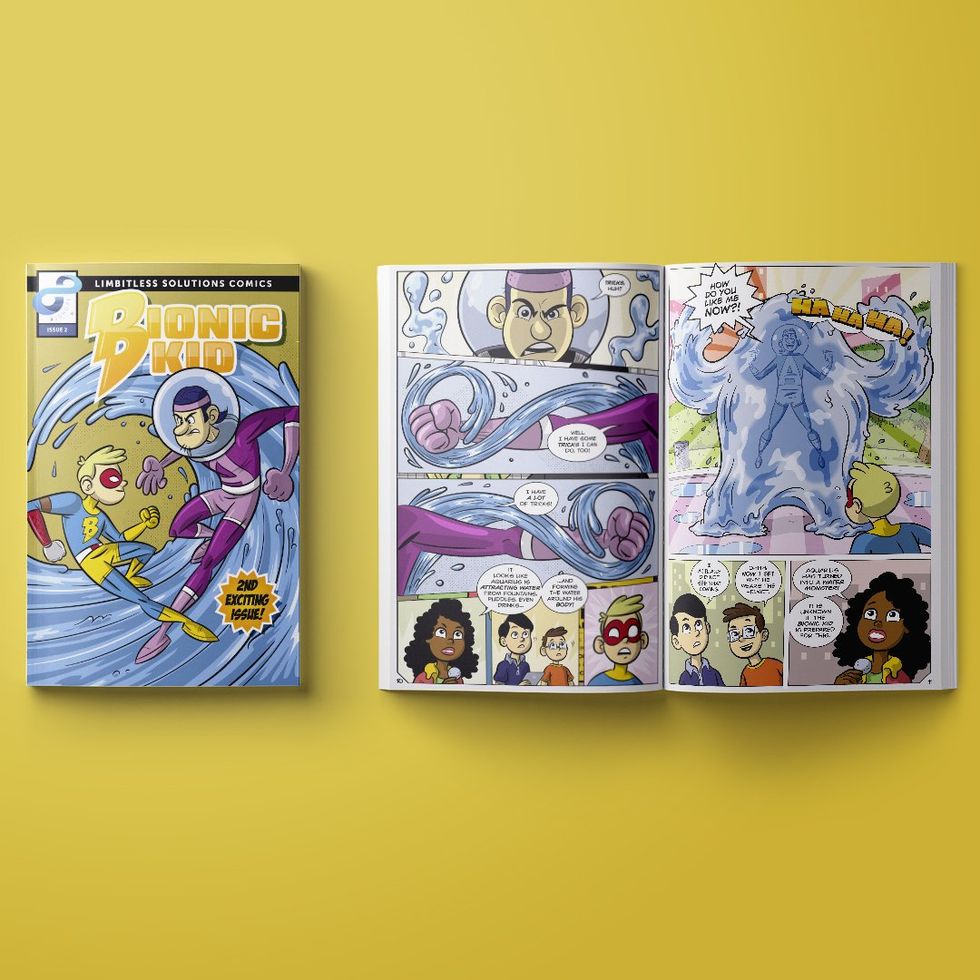

And I am not alone. Many fat people find the doctor’s office — which should be safe, confidential, and constructive — is instead a home for shame and rejection. Health care providers congratulate fat people for their eating disorders, they tell patients they should lose weight if they “want to be beautiful,” and fat people are given lectures on weight loss instead of receiving medical treatment.

Like all of us, health care providers can be products of a culture that teaches us to shame, exclude, and be disgusted with fat people.

Image via iStock.

Often, it can show in their treatment of fat patients.

A growing body of research shows that doctors are less likely to show empathy for fat patients, making many unable to take in important diagnostic information. Doctors are more likely to describe fat patients like me as awkward, unattractive, noncompliant — even weak-willed and lazy. Because despite extraordinary training and expertise in medicine, health care providers are products of a culture that shames and rejects fat people. And those beliefs inform important, sweeping health care policy decisions.

When thin friends and family talk to me about my health, this is a part they almost never imagine: Getting basic health care, from regular check-ups to minor interventions, requires tenacious self-advocacy. Because in the doctor’s office — just like the rest of the world — I am forced to defend my body at every turn just to get my basic needs met. Unlike other patients, I must prostrate myself, prove that I am worthy of treatment.

And that’s made possible by the way we all talk about being fat — all of which muddies our ability to measure health in more complex, precise ways. I think we use “losing weight” and “getting healthy” interchangeably. We reject fat people’s accounts of their own weight loss attempts, opting instead to believe that they simply haven’t tried hard enough, or don’t know how.

When we talk about fatness as the only real measure of health, we bypass many other pieces of the puzzle: nutrition, heart rate, blood pressure, sleep patterns, mental health, family histories. We ignore precise, important measures of health, collapsing all that complexity into the size of someone’s body, believing that to be the most accurate and trustworthy measure of a person’s health. This is what happens to me. My health is disregarded, all because of how I look.

In order to get accurate diagnoses and real treatments to fat patients, we’ll all need to examine our own thinking about fat people and health.

Changing the conversation around fat and health will take more work than that — but it’s a place to start. Because as it stands, few of us are willing to believe that fat people could have health problems stemming from anything other than their fat bodies.

It looks like images you may have seen of early cell division, but this is of individual Chromosphaera perkinsii forming a colony. © UNIGE Omaya Dudin

It looks like images you may have seen of early cell division, but this is of individual Chromosphaera perkinsii forming a colony. © UNIGE Omaya Dudin Aging happens in bursts, scientists find.Photo by

Aging happens in bursts, scientists find.Photo by

The Goldbergs Yes GIF by ABC Network

The Goldbergs Yes GIF by ABC Network