This story was originally published on The Mash-Up Americans.

“When you are in this house, you are in Nigeria; when you are outside of these doors, you are in the USA.”

This was a common refrain from my dad. He and my mom immigrated to the U.S. from Lagos in the '80s to finish university. I was the first in my family to be born in the U.S. — but I lived in an alternate Nigerian-American reality. As a child of Nigerian immigrants growing up in Chicago, code-switching was an art form.

It was particularly tough when it came to school. In a Nigerian household, education is everything. Religion and education are the panacea for all problems. There was no challenge that a Holy book, or a math book, couldn’t solve. School in Nigeria isn’t about making friends or varsity sports or prom queens. It is about putting your head down and studying. The overarching theme is: Work now, play later. By labor comes wealth.

Boyede Sobitan in his happy place. Image via The Mash-Up Americans.

In American schools, fitting in and making friends is of utmost importance. As an African kid in the Midwest with foreign parents — suffice to say that Hollywood did not help me meet those goals.

I love Eddie Murphy, but the movie “Coming to America,” was the worst thing that could have happened to many African immigrants in the '80s and '90s. The accents. The outfits. Everything was terrible, and everybody I met at school thought that’s what my family was like too. Did we have animals walking around our house? The never-ending jokes about what things were like in “Zamunda!” Then there were those awful Christian Children’s Fund ads with the starving African children and constant images of Africa as a place of strife and famine.

Being African was not cool.

Image via iStock.

Food was always a solace, at least at home. But not at school. Try explaining an African meal to an American child in the '80s.

While other kids were eating bologna sandwiches, Fruit Roll-Ups, and Capri Sun, I was eating white rice, egusi stew, and stewed goat meat, my favorite.

To me, it was food. Not only was it food, it was great food. I never noticed the difference in smell between my meals and the other kids’ meals. I thought African food was downright fragrant. In Nigeria, food from home is always the best. But to my American counterparts, it was pungent and offensive, which led to a lot of isolation.

“That’s monkey food, “ or “Is that was what they eat in Africa?” were common retorts. The immense level of shame I felt didn’t go unnoticed at home — where, of course, we were Nigerian through and through.

“Why are you not eating?” my mom would often ask.

“I want some pizza, Ma.”

My mother’s response? To look at me incredulously and snap: “Pizza ko, lasagna ni!” In other words, “You don’t want pizza. You want lasagna!” followed by a hiss. This is a common comeback for many Yoruba people. My mom’s stance was: “If you don’t eat this rice, you won’t eat.” Meals quickly transformed from my favorite time of day to a nightmare.

After a few years, though, the ice began to thaw between me and my classmates — or the jollof began to bridge the gap, as the case may be.

Image via iStock.

Thanksgiving played a huge part in this. It celebrates common values that both Americans and Africans hold dear — faith, family, and food. Thanksgiving is my favorite holiday. We’ve adopted the traditional turkey. But we have included sides like Nigerian salad, moi-moi, jollof rice, fried rice (not the Asian form), and dodo, or fried plantain.

Finally, my two cultures began to merge.

I loved when my “American” friends came over, and I could articulate what we were eating and its significance to my culture. At home, I was in a safe place. My friends were on my territory. I didn’t have to go to the corner to enjoy my food. I could eat my fried goat meat with stuffing or jollof rice with a turkey drumstick. It was, truly, my American dream.

An adorable French Bulldogvia

An adorable French Bulldogvia  french bulldog gifofdogs GIF by Rover.com

french bulldog gifofdogs GIF by Rover.com The first deposit of orange peels in 1996.

The first deposit of orange peels in 1996. The site of the orange peel deposit (L) and adjacent pastureland (R).

The site of the orange peel deposit (L) and adjacent pastureland (R). Lab technician Erik Schilling explores the newly overgrown orange peel plot.

Lab technician Erik Schilling explores the newly overgrown orange peel plot. The site after a deposit of orange peels in 1998.

The site after a deposit of orange peels in 1998. The sign after clearing away the vines.

The sign after clearing away the vines. This is a teacher who cares.

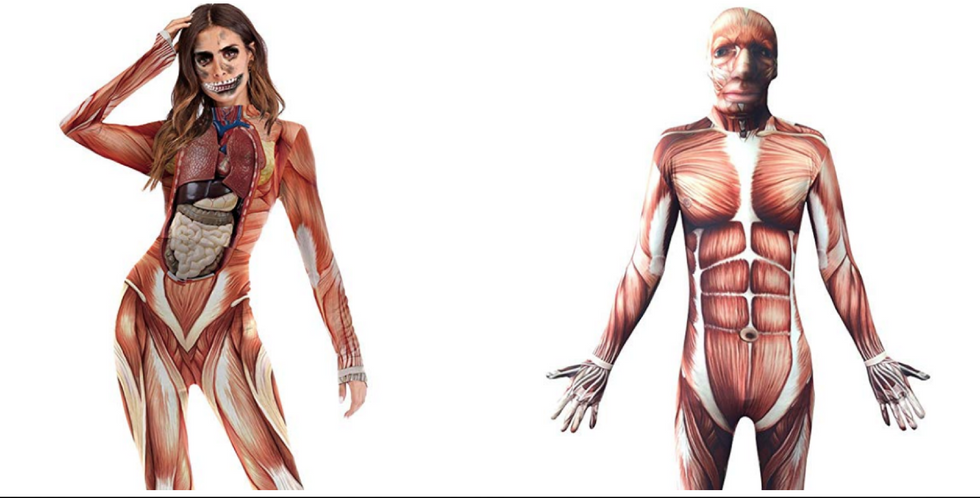

This is a teacher who cares.  Halloween costume, check.

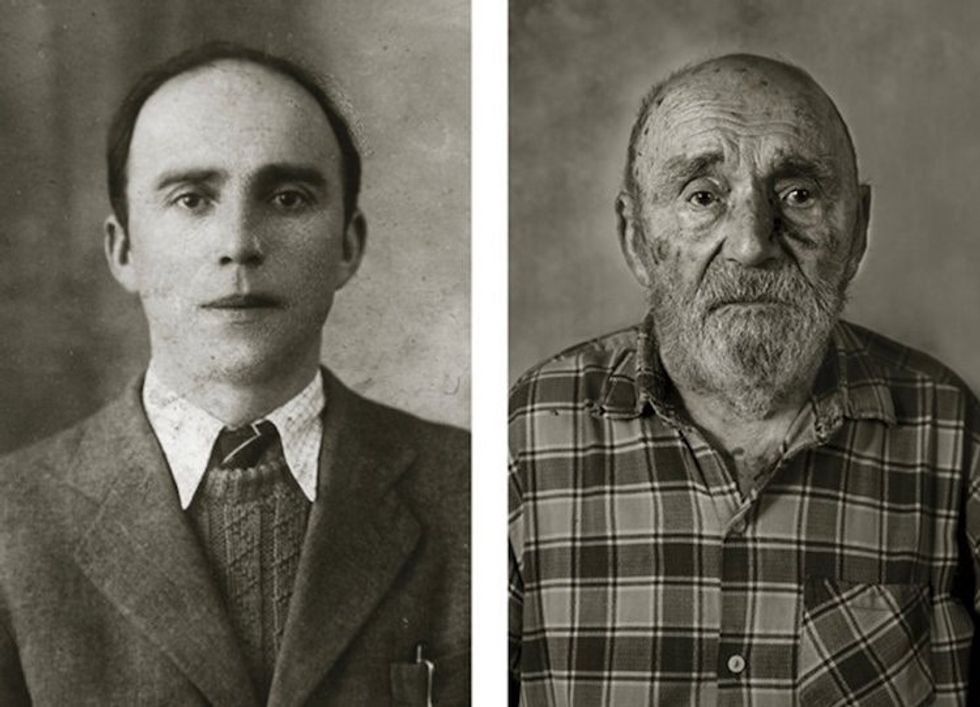

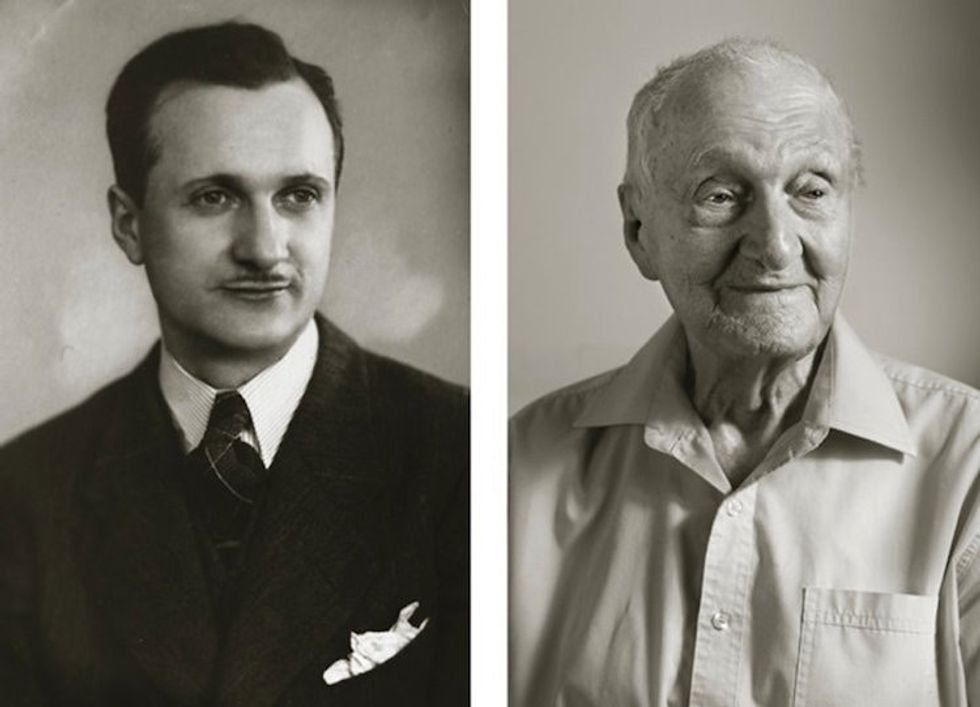

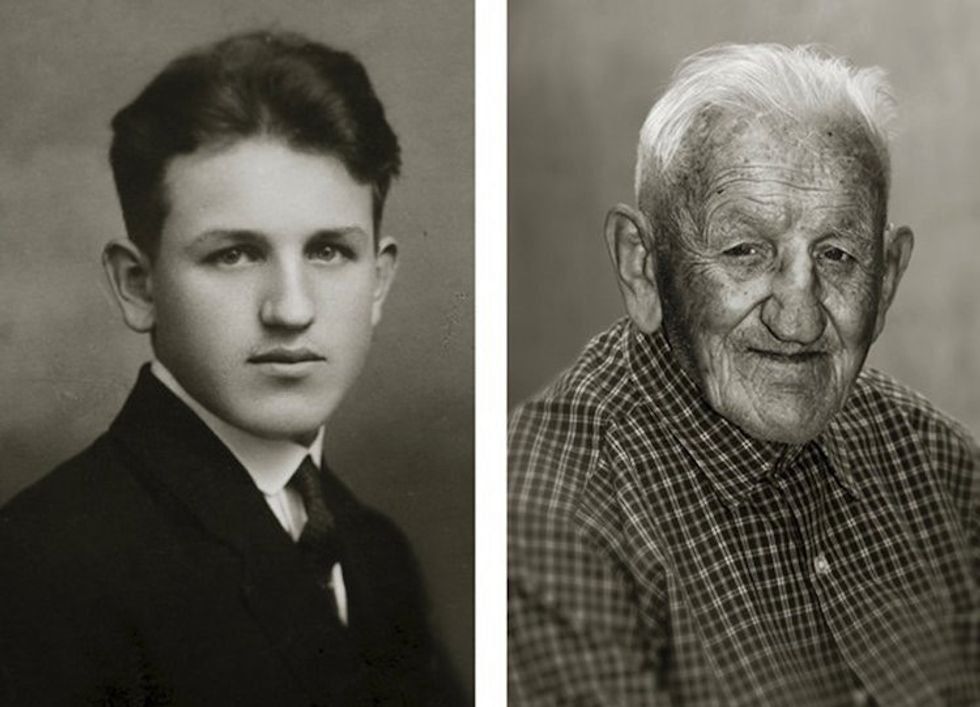

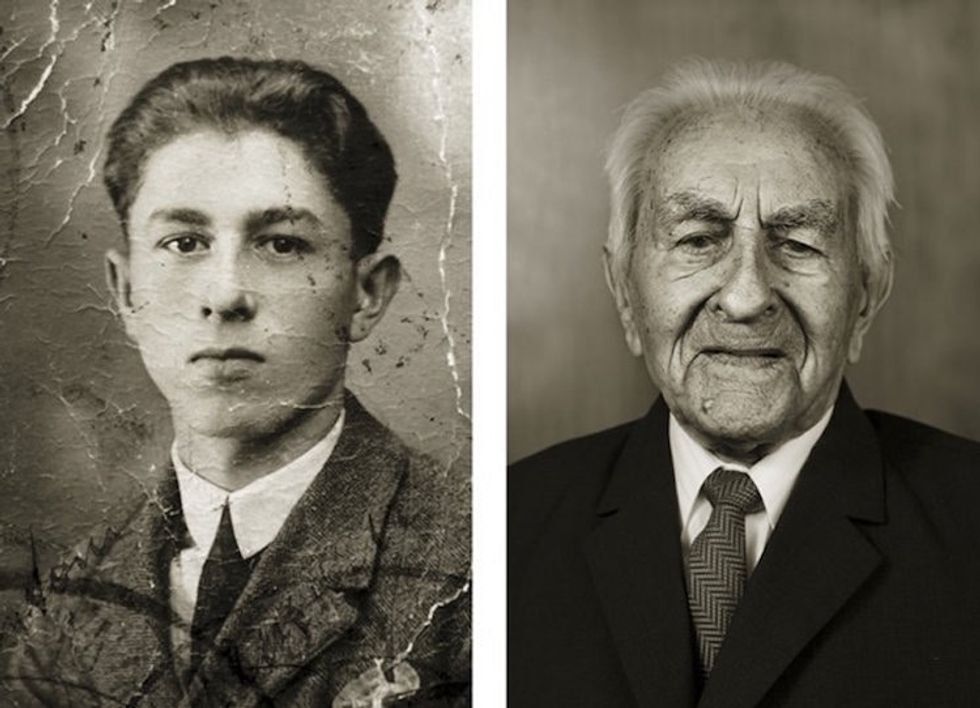

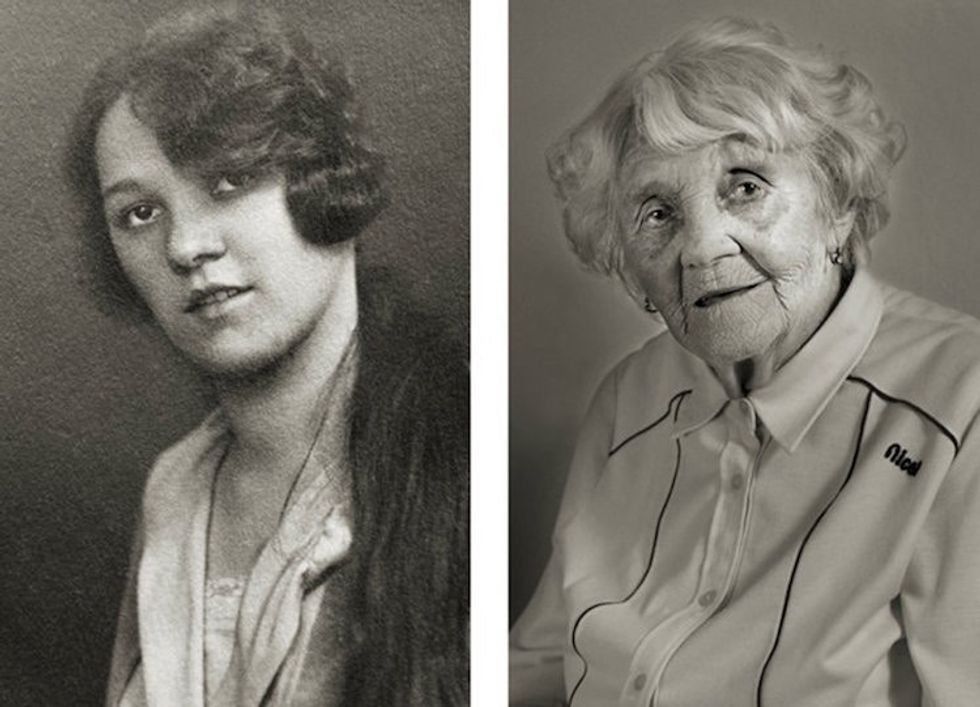

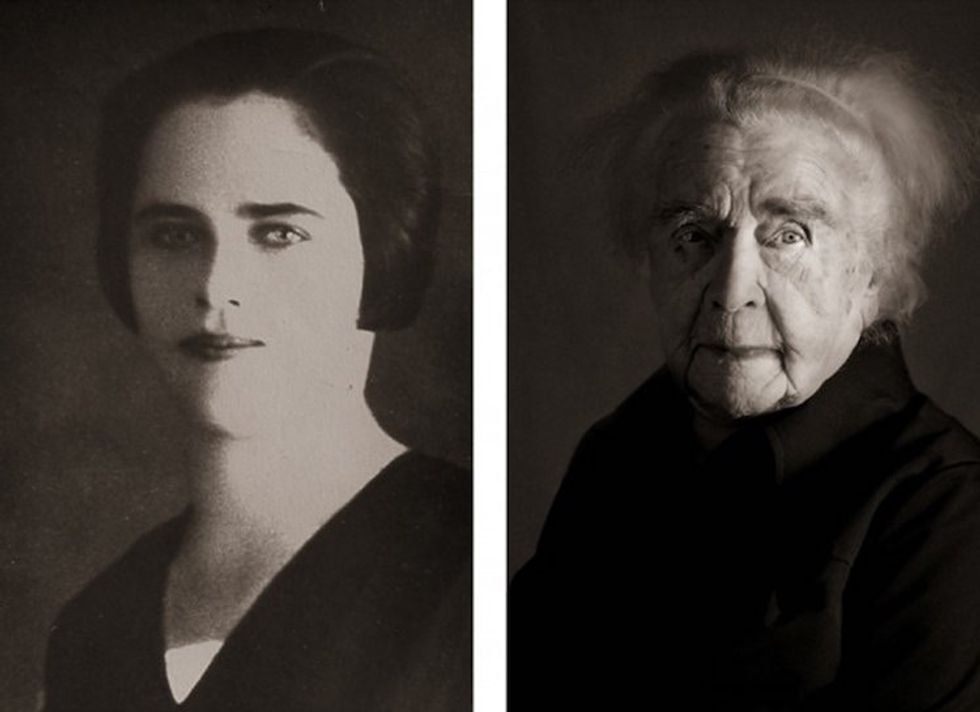

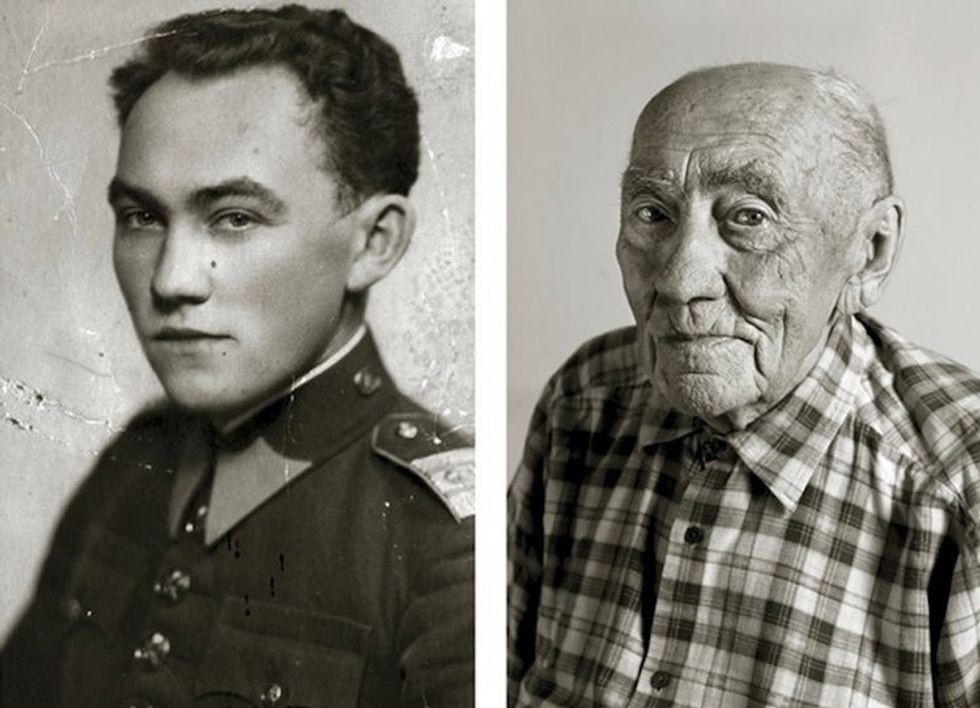

Halloween costume, check.  Prokop Vejdělek, at age 22 and 101

Prokop Vejdělek, at age 22 and 101