Want to see more women calling the shots in Hollywood? Here are 5 things that need to happen.

The numbers don't lie: There are almost zero female directors in Hollywood.

Lena Dunham, one of the few women calling the shots in Hollywood. Photo by Randy Shropshire/Getty Images Entertainment.

That also applies to women in other roles behind the camera, and even in front of it.

In the top 700 grossing films from 2007 to 2014, women made up only 30.2% of speaking roles. In 2014, only 1.9% of directors who made the top 100 grossing films were women. And this is just from one study, conducted by the Media, Diversity, & Social Change Initiative at USC Annenberg.

A recent New York Times article uncovered some reasons (read: excuses) for why this is the case, from studios prioritizing movies with male leads because of foreign audiences to the confounding idea that women don't want to direct blockbusters. (Spoiler alert: They do.)

The whole article is an engrossing, outrage-inducing read. Yet within the many anecdotes from female directors about discrimination they've experienced lie many potential solutions. Here are five:

1. The few women who do have a foot inside Hollywood's door need to support other women.

Apparently, in Hollywood, women don't often find support from other women. Even when some women make it to the top — such as the ones who run two of Hollywood's big six studios — they don't always extend a hand to other female directors or even actresses.

When an industry only makes room for one or two women to succeed, those women are less likely to support other women out of fear that they'll be replaced by the very women they mentored.

Another fear that keeps women from working together in Hollywood is being pigeonholed as someone who can only work on movies for women. Former Sony Co-Chairperson Amy Pascal explained that after producing female-driven hits earlier in her tenure, she felt she wouldn't be given a chance to make more mainstream projects.

Photo by Kevin Winter/Getty Images Entertainment.

As long as it's every woman for herself, women are going to remain tokens in a male-dominated Hollywood. Many of the female directors and producers who spoke to the New York Times stressed the importance of making change by working together.

Pascal herself is getting back to producing movies about women, including the all-female "Ghostbusters" reboot.

2. Men in Hollywood need to mentor outside their comfort zone — i.e., they need to mentor women.

The Times piece opens with the charmed upward trajectory of director Colin Trevorrow, who went to the Sundance Film Festival with an indie romantic comedy. Pixar director Brad Bird ("The Incredibles") then introduced him to Steven Spielberg, who picked Trevorrow to direct "Jurassic World." Bird said he liked Trevorrow because Trevorrow "reminded me of me." Meanwhile, director Leslye Headland also had her indie romantic comedy, "Bachelorette," screen at Sundance and got no such recommendation or opportunity.

There could be many reasons why Headland didn't come away from her Sundance screening with an opportunity like that. But Bird related to Trevorrow because he saw himself in him. So it makes (unfortunate) sense that women are less likely to get the opportunities their male counterparts get simply because the men who offer them don't see themselves reflected in female directors.

Hollywood has to stop thinking of women-driven films as niche, or women directors as too unrelatable to mentor. And men in positions of power in Hollywood need to make sure they're mentoring women just as often as they're mentoring men.

3. The success of people like Shonda Rhimes, Jennifer Lawrence, and Amy Schumer shouldn't be exceptions to the rule.

Photo by Slaven Vlasic/Getty Images Entertainment.

As far as Hollywood is concerned, "The Hunger Games" succeeded only because of Jennifer Lawrence, "Trainwreck" succeeded only because of of Amy Schumer, and "Scandal" and "How to Get Away With Murder" are only successes because of Shonda Rhimes — not because women in general are capable of creating films and shows for a large audience, but because these specific few, rare women are talented enough to have mainstream appeal.

Successful female-driven films and TV shows are thought to be exceptions to the rule, rather than profitable and resonant in their own right. And when a female-driven film or show flops, it's often assumed that it flopped because of women, even though when movies with male leads flop, the overwhelming maleness of the film is never cited as a reason why.

Luckily, there are Hollywood power players who are investing in women-directed films and television shows. Besides Rhimes, a powerful producer and show-runner, there's Reese Witherspoon, Meryl Streep, and Geena Davis, as well as Will Ferrell and Adam McKay, who are all championing female directors, screenwriters, and characters through their nonprofit organizations and production companies.

"If everyone's gonna pass on all the strong, ass-kicking lady directors and writers out there, we'll take them," says McKay.

4. Hollywood needs to let women be themselves on set.

There are two glaring examples of this in the NYT piece. The first is the case of "Twilight" director Catherine Hardwicke, who wasn't considered to direct the rest of the franchise after helming the first movie because she was "overly emotional," crying on set during a particularly hard day. And the second is the great Barbra Streisand, who was derided for being "indecisive" when she asked for input on the set of "Yentl."

Yet directors like David O. Russell keep directing Oscar contenders even after he's come to blows with George Clooney, shouted at Lily Tomlin on set, and allegedly "abused" Amy Adams on the set of "American Hustle," according to the Sony email hack.

Photo by Michael Loccisano/Getty Images Entertainment.

Cinematographer Rachel Morrison told the NYT about how, when she finally couldn't hide her pregnancy anymore, people stopped booking her on jobs.

"It should have been up to me if I was capable to work or not," Morrison said. As much as male directors are given free rein over their sets and their schedules — and their emotional outbursts — the same opportunities should be available to women.

5. Women should feel just as empowered and entitled to help themselves as their male peers do.

It's inevitable that all this sexism is internalized, at least somewhat. Which is probably why Lucasfilm President Kathleen Kennedy told the Times that no woman expressed interest to her in directing "Star Wars." It's also why, as director Allison Anders explained, that in Hollywood negotiations, "The men are like: 'Oh please, yes. I want to do this.' Women are a little too suspicious, too cautious and a little too precious about their reality."

This is the "Lean In" phenomenon. Women need to lean in and ask for more in order to get success. And that's good advice for individual women to internalize, but does it help on a systemic level?

As "Girls" creator Lena Dunham pointed out, there is a flaw in putting the pressure on women to fix the problems in a system where sexism is so prevalent and power is so often held by men:

"I feel like we do too much telling women: 'You aren't aggressive enough. You haven't made yourself known enough.' And it's like, women shouldn't be having to hustle twice as fast to get what men achieve just by showing up."

So how do we fix this?

We're seeing progress, slowly but surely, as more and more female-driven films and shows succeed. And even industry executives can't deny the pattern of what shows and movies are bringing in the most money.

But there are two things that need to happen to make sure this progress continues until we reach a point of gender parity: One, women have to fight for themselves and support each other, and two, men have to support women too.

A father does his daughter's hair

A father does his daughter's hair A father plays chess with his daughter

A father plays chess with his daughter A dad hula hoops with his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad hula hoops with his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. A dad talks to his daughter while working at his deskAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad talks to his daughter while working at his deskAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. A dad performs a puppet show for his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad performs a puppet show for his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. A dad walks with his daughter on his backAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad walks with his daughter on his backAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. a dad carries a suitcase that his daughter holds onto

a dad carries a suitcase that his daughter holds onto A dad holds his sleeping daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad holds his sleeping daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. A superhero dad looks over his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A superhero dad looks over his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. A dad takes the small corner of the bed with his dauthterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad takes the small corner of the bed with his dauthterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. Yorkie GIF

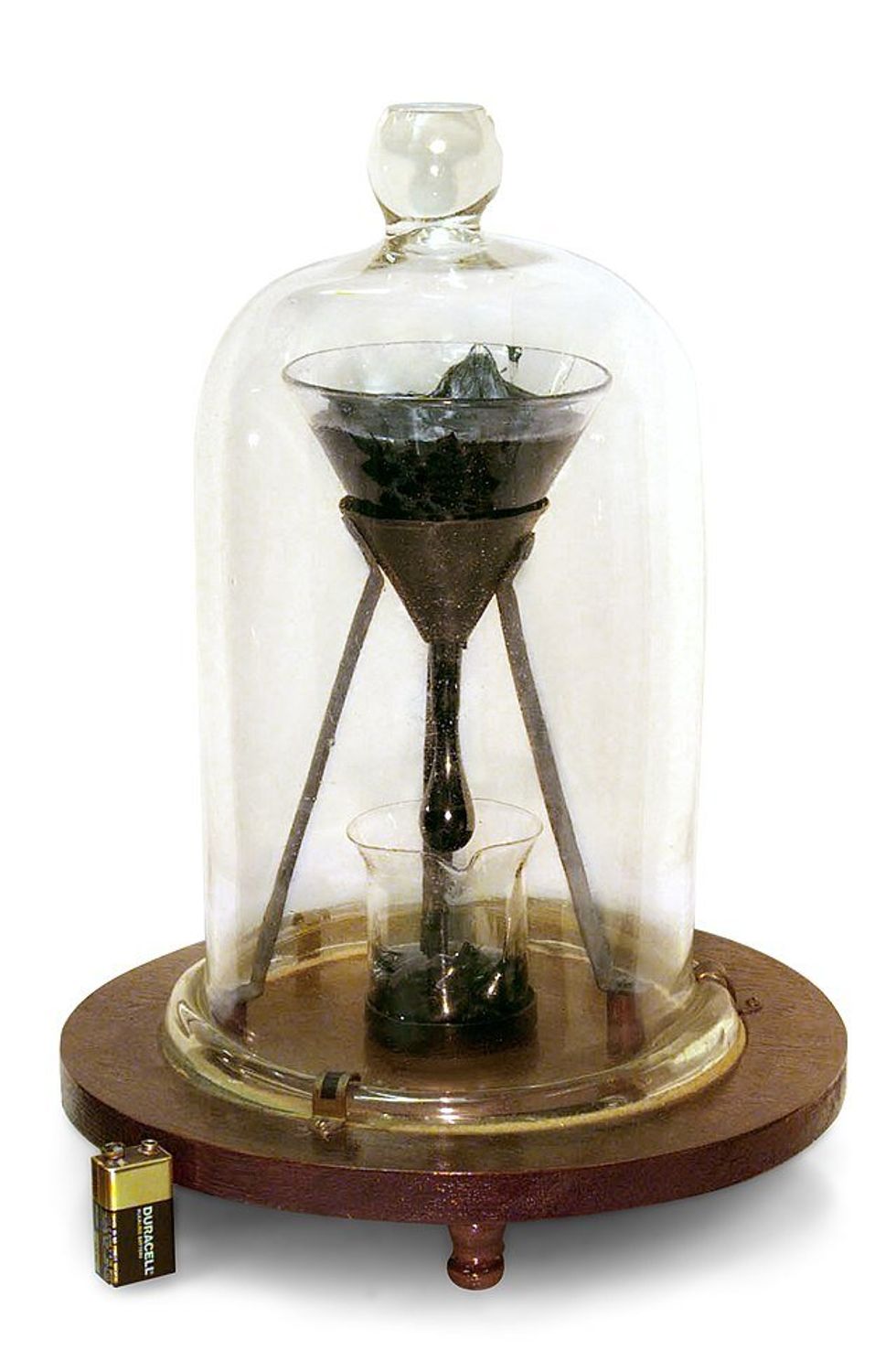

Yorkie GIF Pitch moves so slowly it can't be seen to be moving with the naked eye until it prepares to drop. Battery for size reference.

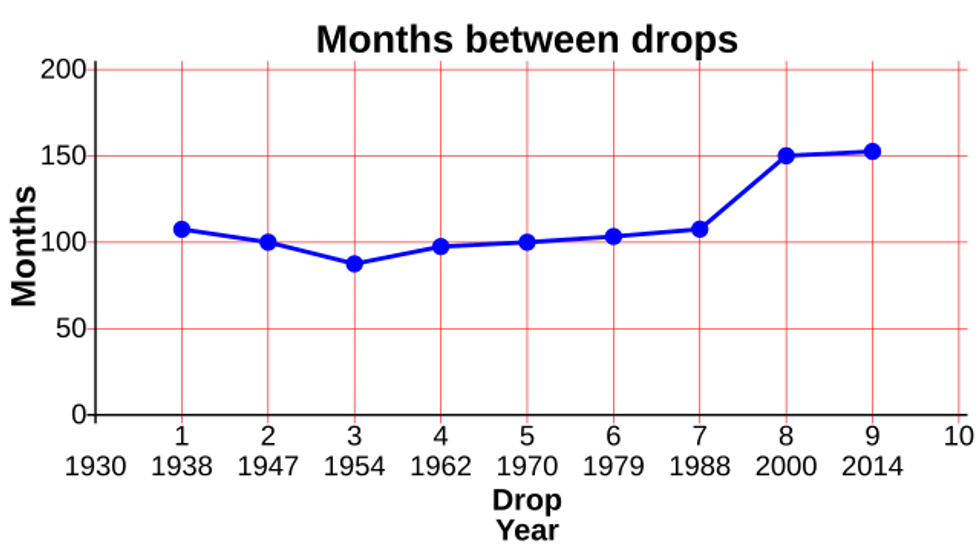

Pitch moves so slowly it can't be seen to be moving with the naked eye until it prepares to drop. Battery for size reference. The first seven drops fell around 8 years apart. Then the building got air conditioning and the intervals changed to around 13 years.

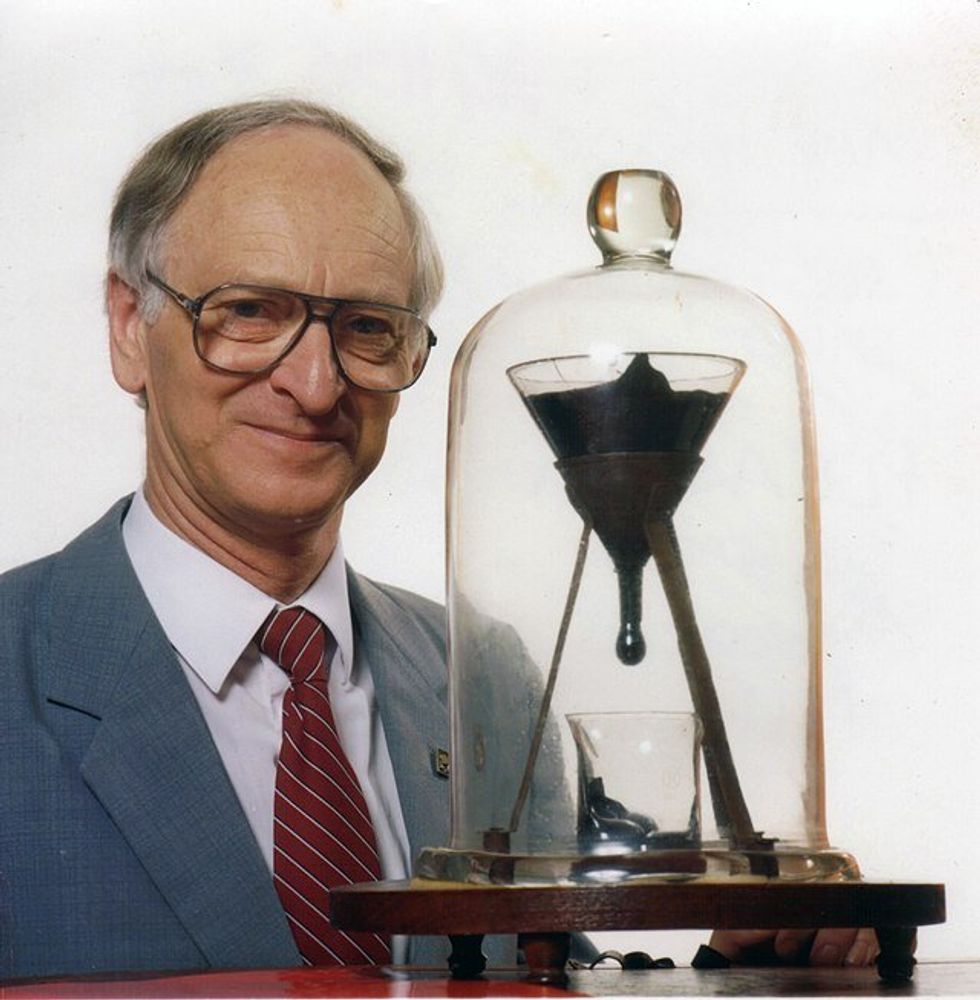

The first seven drops fell around 8 years apart. Then the building got air conditioning and the intervals changed to around 13 years. John Mainstone, the second custodian of the Pitch Drop Experiment, with the funnel in 1990.

John Mainstone, the second custodian of the Pitch Drop Experiment, with the funnel in 1990. shocked cat GIF

shocked cat GIF Bored Cat GIF

Bored Cat GIF