In 2013, North Carolina legislators tried to make some major changes to the state's voting laws, many of which would affect the voting rights of black Americans.

Legislators argued that the new laws — which included changes to ID requirements, early voting practices, and same-day voter registration — were put forward to prevent voter fraud.

A federal appeals court struck them down in the summer of 2016 and actually said the laws were "as close to a smoking gun as we are likely to see in modern times. [...]We can only conclude that the North Carolina General Assembly enacted the challenged provisions of the law with discriminatory intent."

Photo by Sarah D. Davis/Stringer/Getty Images.

You might be thinking, "Well, what's wrong with having to show ID at the polls?" To answer that, we'll have to look back 50 years, to the height of the Civil Rights Movement.

Before the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, black Americans were technically allowed to vote. But they had to jump through plenty of hoops to actually get to the voting booth.

Even when they did make it to the polls, some states still required them to prove their "good character." That usually meant showing an ID and proving a basic level of education, literacy, and civic knowledge. (And also that they weren't common-law married and didn't have an "illegitimate" child. Ugh.)

As you can probably imagine, this was easier said than done. Take a look for yourself.

Here's a sample of a test given to black voters in 1960s Mississippi:

Image from the Jim Crow Museum at Ferris State University.

It reads:

Write and copy in the space below: Section [blank] of the Constitution of Mississippi: (Instruction to Registrar: You will designate the section of the Constitution and point out same to applicant.)

Write in the space below a reasonable interpretation (the meaning) of the section of the Constitution of Mississippi which you have just copied:

Write in the space below a statement setting forth your understanding of the duties and obligations of citizenship under a constitutional form of government.

In Louisiana, black voters only had to get 4 of 6 questions correct on a civic literacy exam cards like this — if they were lucky.

Image from Civil Rights Movement Veterans organization.

This one says:

1. The Congress cannot regulate commerce (a) between States; (b) with other countries; or (c) within a state.

2. The general plan of a State government is given (a) in the Constitution of the United States; (b) in the laws of the Congress; or (c) in its own State constitution.

3. The name of our first President was (a) John Adams; (b) George Washington; or (c) Alexander Hamilton.

4. The President gets his authority to carry out laws (a) from the Declaration of Independence; (b) from the Constitution; or (c) from the Congress.

5. Our towns and cities have delegated authority which they get from the (a) State; (b) Congress; or (c) President.

6. A citizen who desires to vote on election day must, before that date, go before the election offers and (a) register; (b) pay all of his bills; or (c) have his picture taken.

These don't seem so tricky — again, if you've had an education and can still remember what Ms. Lupi said in eighth grade. But even then, I still got tripped up on two of them.

But a few very unlucky black voters had to complete a crazy-complicated 30-question riddle game in 10 minutes flat.

There's not much information about what circumstances justified this crazy trap beyond a generalized "racism," and it was certainly rare — but wow, is it ridiculous. Here's a sampling:

Image from Civil Rights Movement Veterans organization.

Those instructions read:

10. In the first circle below write the last letter of the first word beginning with "L."

11. Cross out the number necessary, when making the number below one million.

12. Draw a line from circle 2 to circle 5 that will pass below circle 2 and above circle 4.

Black voters had 10 minutes to answer 30 questions like this. Which meant that, unless you possessed some sort of acrobatic brain powers, you probably weren't going to be able to vote that year.

Of course, if you did fail whatever test you were given, the registrar (who was definitely white) could still approve of your right to vote. If they wanted to.

Photo by Davis Turner/Getty Images.

If these tests seem absurd, it's because they are. But they're not so different from the laws in North Carolina that were just struck down.

Requiring voters to present a photo ID from the DMV might not sound ridiculous on the surface. But when that just so happens to be the specific ID that's owned by a disproportionate minority of blacks in North Carolina? Something's up. (ID laws in general tend to affect minorities the most.)

The same thing happened when the state tried to abolish voting on Sundays as black communities are the ones who tend to take advantage of early voting on a Sunday. And again when North Carolina tried to shorten the early voting period from 17 days to 10 days when black citizens were significantly more likely to vote in those first seven days.

But it's not about early voting or Sundays or photo IDs. Just like it was never about literacy.

Photo by Sara D. Davis/Stringer/Getty Images.

Voter fraud is still an issue though, especially in a presidential election. But not in the way that some people think it is.

In one study of elections since 2000 — the year of the highly contended Bush-Gore election — a Loyola Law School professor found about 31 cases of individuals committing voter fraud at the polls out of more than a billion ballots cast. Another look by the Justice Department identified 86 cases between 2000 and 2005, which is still a pretty small number.

And yet, this election year, more than 30 states will require photo IDs for voters, allegedly to cut down on acts of fraud.

Photo by Mark Makela/Getty Images.

Elections aren't rigged by a few sneaky individuals casting double ballots or lying about their names; it happens when the people in power tamper with technology or manipulate turnouts with the help of things like ID laws and gerrymandering that impede individuals from exercising their democratic rights.

A democracy only works when everyone has a voice — regardless of race, gender, beliefs, education, or even possession of a photo ID.

So instead of trying to fight a nonexistent issue like voter fraud, maybe we should focus our energies on educating people about the choices they're making and finding easier ways to get them to the polls.

Potted plants and herbs can thrive in a container garden.

Potted plants and herbs can thrive in a container garden. Freshly harvested potatoes are so satisfying.

Freshly harvested potatoes are so satisfying. Do you see a box or do you see a planter?

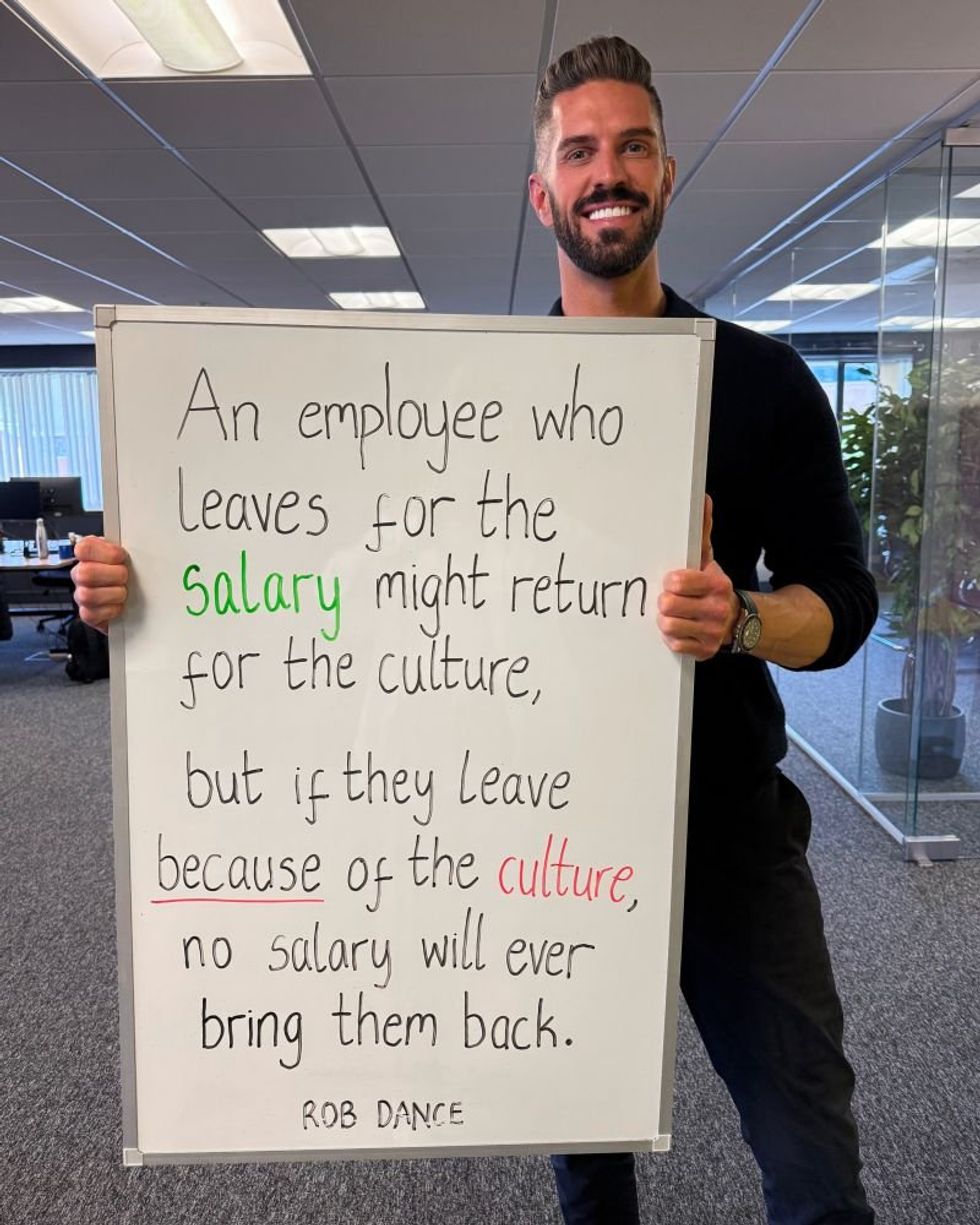

Do you see a box or do you see a planter? CEO Rob Dance holds up a whipe board with his culture philosophy.

CEO Rob Dance holds up a whipe board with his culture philosophy.  A pair of hands holding another pair of hands.

A pair of hands holding another pair of hands.