Terrifying Tyrannosaurs were social creatures who hunted together like wolves, new research says

When we think of what a Tyrannosaurus looked like, we picture a gargantuan dinosaur with a huge mouth, formidable legs and tail, and inexplicably tiny arms. When we picture how it behaved, we might imagine it stomping and roaring onto a peaceful scene, single-handedly wreaking havoc and tearing the limbs off of anything it can find with its steak-knife-like teeth like a giant killing machine.

The image is probably fairly accurate, except for one thing—there's a good chance the T. rex wouldn't have been hunting alone.

New research from a fossil-filled quarry in Utah shows that Tyrannosaurs may have been social creatures who utilized complex group hunting strategies, much like wolves do. The research team who conducted the fossil study and made the discovery include scientists from the U.S. Bureau of Land Management, Denver Museum of Nature and Science, Colby College of Maine, and James Cook University in Australia.

The idea of social Tyrannosaurs isn't entirely new—Canadian paleontologist Philip Curie floated the hypothesis 20 years ago upon the discovery of a group of T. rex skeletons who appeared to have died together—but it has been widely debated in the paleontology world. Many scientists have doubted that their relatively small brains would be capable of such complex social behavior, and the idea was ridiculed by some as sensationalized paleontology PR.

However, another mass Tyrannosaurus death site found in Montana lent scientific credence to the theory, and now the Utah discovery has provided even more evidence that these massive creatures weren't solitary predators, but social hunters.

"The new Utah site adds to the growing body of evidence showing that Tyrannosaurs were complex, large predators capable of social behaviors common in many of their living relatives, the birds," said Joe Sertich, curator of dinosaurs at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science. "This discovery should be the tipping point for reconsidering how these top carnivores behaved and hunted across the northern hemisphere during the Cretaceous."

The Utah site, known as the Rainbows and Unicorns Quarry (yes, really), has provided paleontologists a wealth of fossils since its discovery in Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument in 2014. Such sites are rare, and the findings in them are often difficult to interpret.

"We realized right away this site could potentially be used to test the social Tyrannosaur idea. Unfortunately, the site's ancient history is complicated," said U.S. Bureau of Land Management paleontologist Dr. Alan Titus. "With bones appearing to have been exhumed and reburied by the action of a river, the original context within which they lay has been destroyed. However, all has not been lost."

Researchers used a multi-disciplinary approach, examining the physical and chemical evidence to determine that a group of 12 Tyrannosaurs at the Utah site were likely killed during a flood that washed their remains into a lake. "None of the physical evidence conclusively suggested that these organisms came to be fossilized together, so we turned to geochemistry to see if that could help us," said Dr. Celina Suarez of the University of Arkansas. "The similarity of rare earth element patterns is highly suggestive that these organisms died and were fossilized together."

The Tyrannosaurus fossils are dated at 76.4 million years old. The research team has also found fossils from seven species of turtles, multiple fish and ray species, two other kinds of dinosaurs, and a nearly complete skeleton of a juvenile (12-foot-long) Deinosuchus alligator.

It's always a fun day when we find out one of history's most terrifying creatures is even more terrifying than we believed. One Tyrannosaurus sounds scary enough, but a group of them strategizing to hunt? That's definitely worse, like a coordinated troupe of Godzillas. No thanks, Cretaceous Period. We're good here.

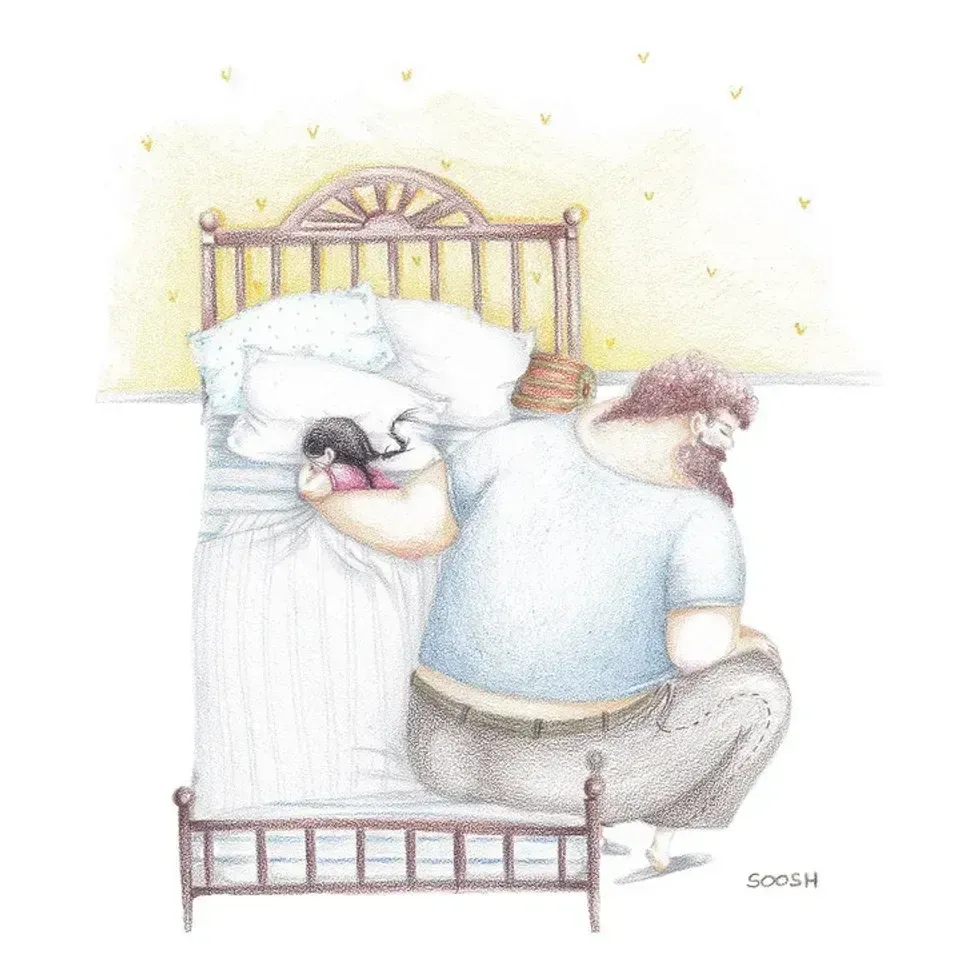

A father does his daughter's hair

A father does his daughter's hair A father plays chess with his daughter

A father plays chess with his daughter A dad hula hoops with his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad hula hoops with his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. A dad talks to his daughter while working at his deskAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad talks to his daughter while working at his deskAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. A dad performs a puppet show for his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad performs a puppet show for his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. A dad walks with his daughter on his backAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad walks with his daughter on his backAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. a dad carries a suitcase that his daughter holds onto

a dad carries a suitcase that his daughter holds onto A dad holds his sleeping daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad holds his sleeping daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. A superhero dad looks over his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A superhero dad looks over his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. A dad takes the small corner of the bed with his dauthterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

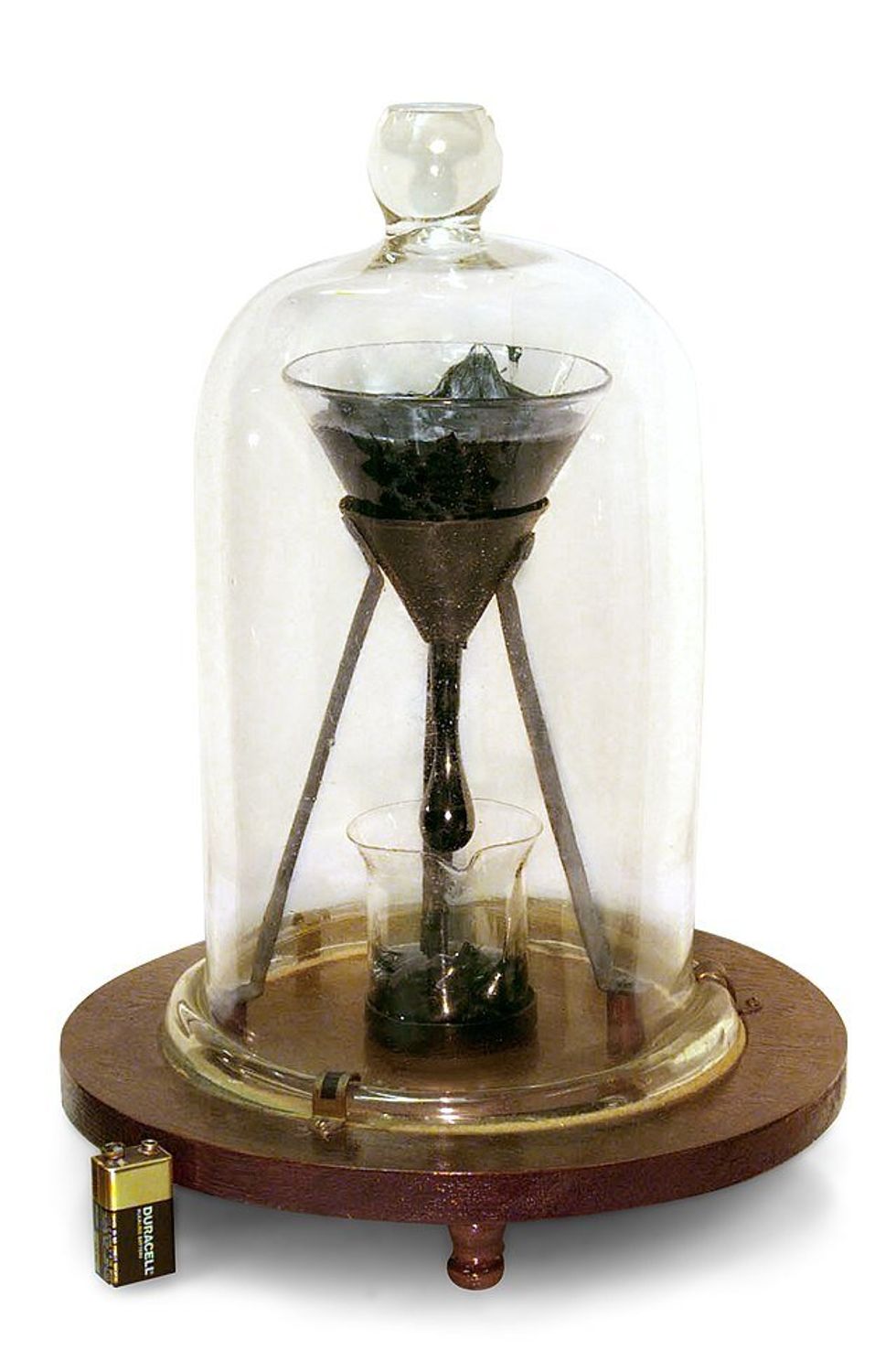

A dad takes the small corner of the bed with his dauthterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. Pitch moves so slowly it can't be seen to be moving with the naked eye until it prepares to drop. Battery for size reference.

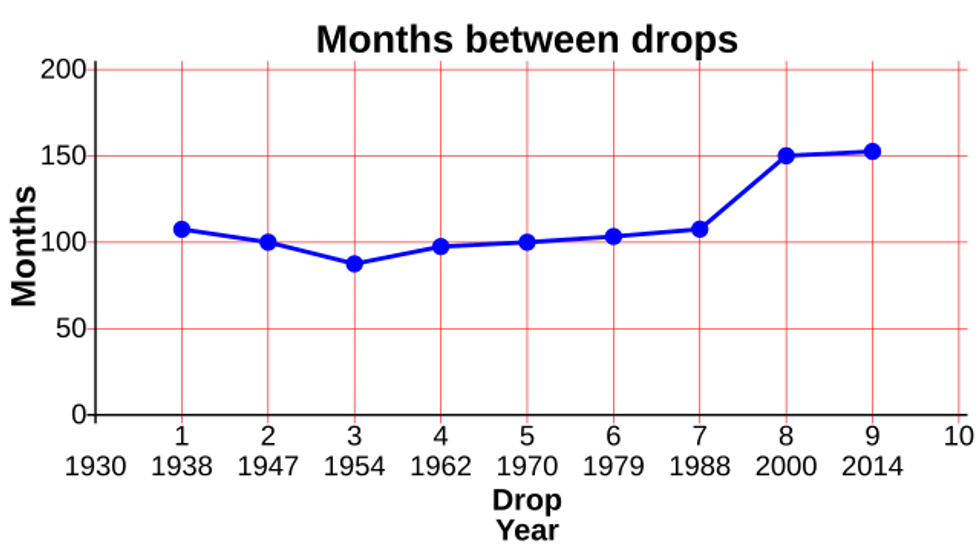

Pitch moves so slowly it can't be seen to be moving with the naked eye until it prepares to drop. Battery for size reference. The first seven drops fell around 8 years apart. Then the building got air conditioning and the intervals changed to around 13 years.

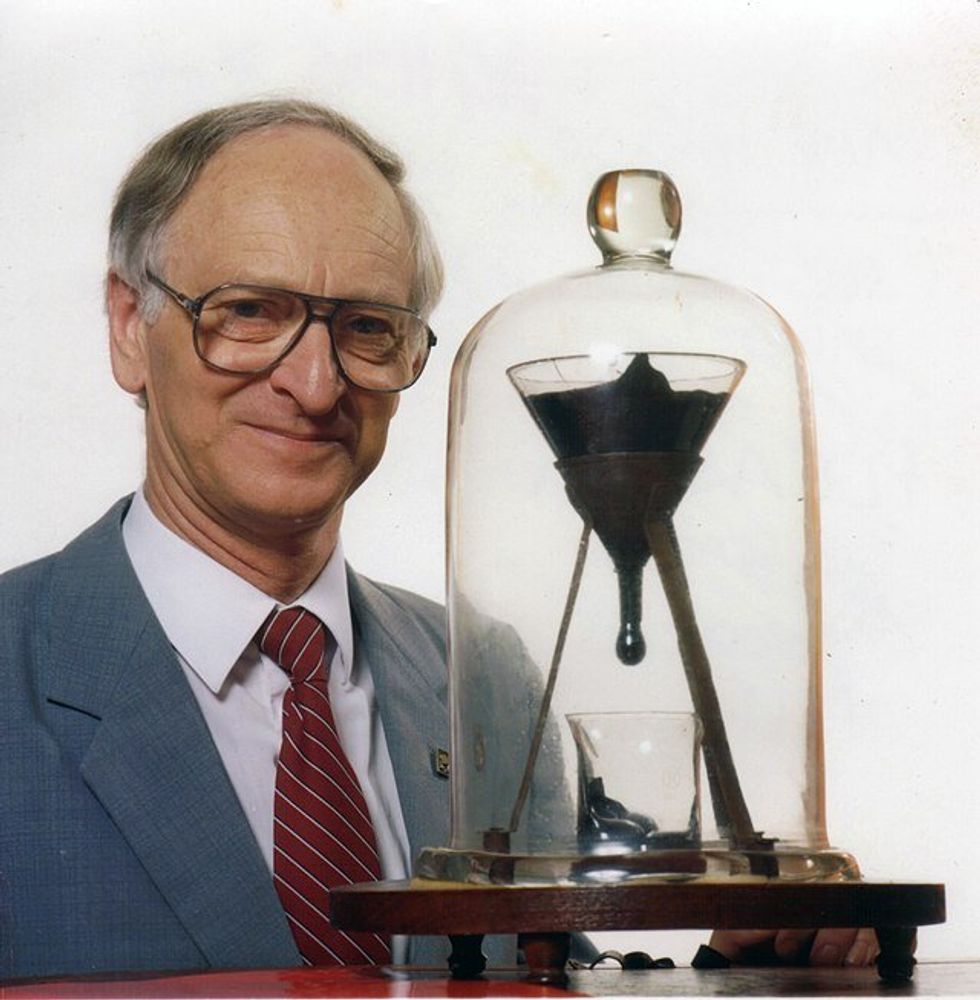

The first seven drops fell around 8 years apart. Then the building got air conditioning and the intervals changed to around 13 years. John Mainstone, the second custodian of the Pitch Drop Experiment, with the funnel in 1990.

John Mainstone, the second custodian of the Pitch Drop Experiment, with the funnel in 1990. A man yelling at a spam call. via

A man yelling at a spam call. via  A spam call boss.via

A spam call boss.via