By outside appearances, Jake Clark seemed to have it all.

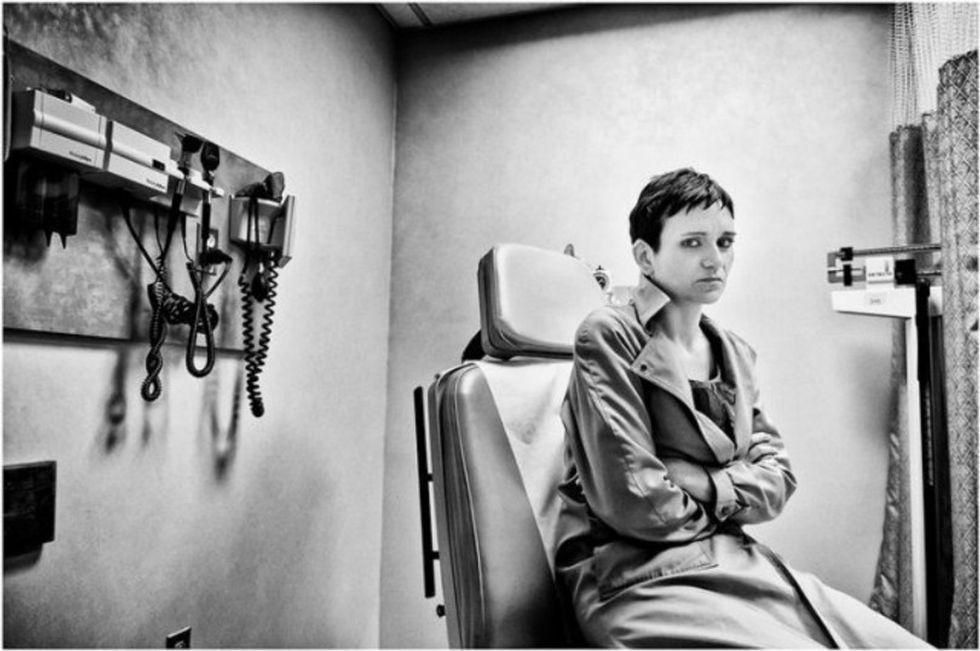

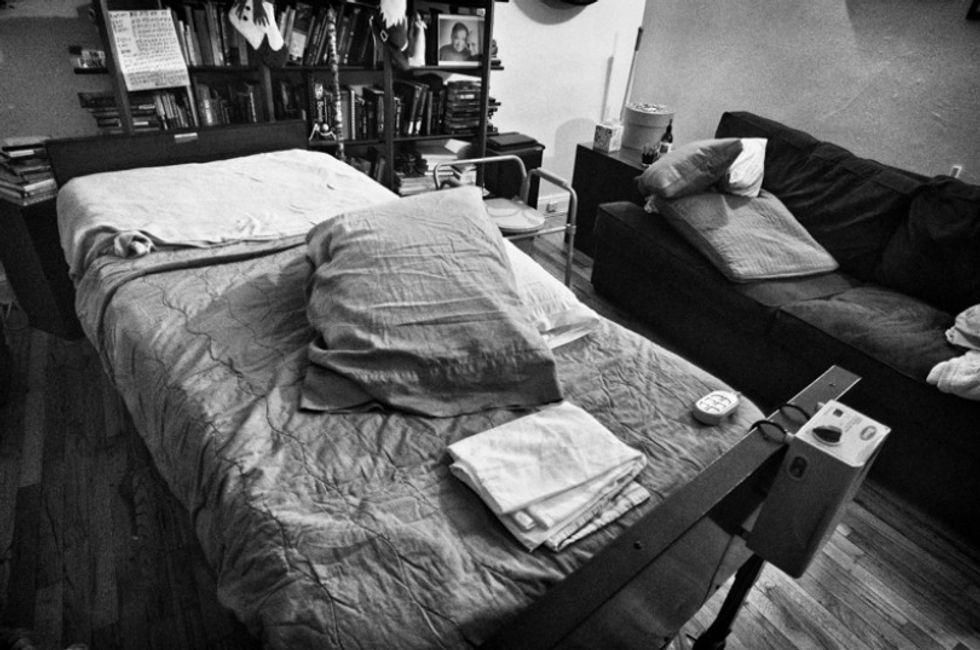

Despite all his achievements — which included work in the U.S. armed forces, law enforcement, the Secret Service, and the FBI — he was feeling suicidal. Most nights, he'd glance over at the pistol sitting at the foot of his bed, picturing himself ending his own life.

He had started to feel this way while working at the FBI, and it led him to pursue unhealthy and even abusive relationships, make futile attempts at self-medicating, and feel prone to anger, insecurity, and resentment. He struggled to connect with others. At times, he was barely present, simply going through the motions.

"I just hated myself — and I didn't know why," he explains. "[I thought,] if people only knew who I really was underneath all of this, they'd never even let me into these agencies."

Photo via Jake Clark.

While Clark left the FBI in 1997 and started to seek out support groups, it took him more than a decade after to find real relief.

When he discovered transcendental meditation in 2012, Clark says it was a game changer.

Transcendental meditation is a form of meditation that uses repetition of silent sounds, called mantras, to bring greater ease, calm, and awareness to one's life. Each student is given their own mantra by a teacher who walks them through the technique.

Through this meditation practice, Clark found something that worked for him. Transcendental meditation helped him establish a greater openness and awareness and was an important addition to his recovery community. Eventually, his suicidal thoughts began to lift.

Reflecting back, Clark realized that much of his struggles had to do with shame.

"You know, when people do something wrong and make a mistake, they'll say, 'I made a mistake,'" Clark explains. "[But] what my internal dialogue said was, 'I am a mistake.'"

Sometimes it can feel impossible for people who are struggling with those feelings to ask for help. "We're terrified to venture out into the world and allow ourselves to be fully seen."

[rebelmouse-image 19397405 dam="1" original_size="885x495" caption="Clark, holding theEagle Rare Life Award. Photo by Gary Miller." expand=1]Clark, holding theEagle Rare Life Award. Photo by Gary Miller.

Clark knew that his experiences weren't uncommon, especially in his line of work.

He'd met countless others, veterans and civilians alike, who had trouble opening up about their trauma. "That's why the suicide rates are so high in the military, law enforcement, [and] first responder space," he says.

Abuse and neglect in childhood was a story he'd heard time and time again, from those he worked with and later as an advocate. "We kept ourselves busy in covering up our pain — by pretending that we're not pretending."

"That's the thing about children who are abused," he continues. "We lock ourselves into these prisons of isolation that lock from the inside."

People in these professions are expected to be tough and unemotional, so when they struggle, they often choose to go it alone. They rarely reach out for help, even when they become suicidal.

Clark knew these wounded warriors needed a space to be vulnerable, dropping the mask and opening up about what they’ve been dealing with.

That's why Clark created Save a Warrior in 2012, a program that supports vets, first responders, and law enforcement who are grappling with post-traumatic stress.

Over five-and-a-half days, attendees at Save a Warrior learn to develop their own meditation and mindfulness practice. This means warriors have to face themselves and their pain head-on and learn to sit with it, even when it's uncomfortable.

"I've seen people work through their fear wholeheartedly," he says. "It's why I keep doing it."

Photo by Jake Clark.

There's also education around the impact of trauma, communication skills, and the importance of self-care. They even watch films and study mythology, exploring themes that are relevant to their experiences and struggles. It's all in an effort to give warriors what they need to thrive when they return home.

But one of the keys to their success, Clark says, is the community that develops throughout the process. With team-building exercises and by simply sharing their stories with one another, these people are learning to show up and be honest about what they're going through. By connecting with each other, they're able to acknowledge and address the pain they've carried, unresolved, for too long.

After all, Clark says, "trauma needs a witness."

Admitting we're vulnerable can be terrifying, especially when we're taught that it's a weakness. But opening up actually takes incredible strength.

"[That's] how I define courage," Clark says. "Being afraid and doing it anyway."

Clark might not still be here if he hadn't been willing to share his story and ask for help. And now, he's teaching other warriors like him — and anyone else who's struggling with their mental health — that asking for help isn't a weakness. In fact, it's just the opposite.

Reaching out doesn't take the pain away, but it does ensure that no one has to go through it alone. And that, Clark says, can be liberating.

"I'm not trapped anymore," he says. "[I realized] the harder things get, the more vulnerable we need to make ourselves."

While a career in the military made him tough, it was only when he opened up that Clark found his true strength.

Potted plants and herbs can thrive in a container garden.

Potted plants and herbs can thrive in a container garden. Freshly harvested potatoes are so satisfying.

Freshly harvested potatoes are so satisfying. Do you see a box or do you see a planter?

Do you see a box or do you see a planter?

Courtesy of Kerry Hyde

Courtesy of Kerry Hyde Courtesy of Kerry Hyde

Courtesy of Kerry Hyde Courtesy of Kerry Hyde

Courtesy of Kerry Hyde Courtesy of Kerry Hyde

Courtesy of Kerry Hyde Angelo and Jennifer drink beers

Angelo and Jennifer drink beers Jennifer holds Angelo

Jennifer holds Angelo