This family has been designing fireworks shows for 166 years. They explain how it's done.

Phil Grucci is rewarding himself after a three-mile run. He left work at 2:30 a.m. and had to be back at 8. But the run couldn't wait.

Phil Grucci (center-left) accepts an award for pulling off the largest fireworks show in history. Photo via Fireworks by Grucci/Facebook, used with permission.

"I got my three miles in, then I put a nice New York bagel onto the plate. I do that so I can have a bagel," Phil told Upworthy on his way out of the kitchen.

He could be forgiven for keeping an extreme schedule. It's three days before the Fourth of July, and it's Phil's job to coordinate and execute dozens of fireworks shows across the country.

"We have to make sure that a load coming up from our Virginia factory makes it through the city by six o’clock in the morning," he said.

Because of security concerns, no explosives can be moved through New York City during rush hour — 6 to 10 a.m. and 3 to 6 p.m.

Making sure that Phil's trucks make it over the George Washington Bridge with enough time to reach their destination on schedule requires careful planning, and the margin for error is razor-thin.

The George Washington Bridge. Photo by Jim Harper/Wikimedia Commons.

"It’s critical to hit that window before that closure happens," he said.

Every Fourth of July, millions of Americans watch fireworks explode — from beach blankets, out windows, or on TV.

Photo by Anthony Quintano/Flickr.

We watch them explode. We ooh and aah. We eat our soft-serve ice cream.

It's amazing.

But most of us have no idea how it all works.

"We start with a blank piece of paper."

Phil is the CEO and creative director of Fireworks by Grucci, a company that has been designing and producing fireworks shows since 1850, when Phil's great-great-grandfather began launching them over the Adriatic Sea in Bari, Italy.

Since then, no two of the company's fireworks shows have been the same.

Photo via Fireworks by Grucci/Facebook, used with permission.

"People don’t generally understand the amount of effort, and certainly creativity and planning, that goes into any firework performance," Phil said. "You don’t just have the fireworks sitting on the shelf labeled firework show A, B, C, D."

When work begins on a new show, Phil meets with a team of designers — a "think tank" — to start sketching out the show length, music required, types of fireworks needed, and dramatic arc of the show.

A Grucci fireworks show in New York City for Chinese New Year. Photo via Fireworks by Grucci/Facebook, used with permission.

Their ideas become a large spreadsheet, which then becomes actual, real-life explosives, specially manufactured at the Virginia factory, which are then transported by truck to the launch site and assembled by a team of dozens of pyrotechnicians — all in preparation for the big moment.

The process takes months. The show is often over in less than 20 minutes.

"It’s a tremendous honor for us to have that ability to be on stage — even though it’s not us personally — for our art form," he said. "Our imagination is on that stage for that 20-minute period of time."

For a firework event to succeed, it needs an emotional arc — a bold opening, followed by rising action, with a peak somewhere near the middle before "intermission," Phil says — like a Broadway show.

After the break, he explains, the tension should ebb and flow, until ratcheting up for a spectacular closing sequence, which should leave no doubt that the show is over.

"When we put on a good performance, a fantastic, well-thought-out, well-choreographed program, the show could be six-minutes long, and when the audience walks away fully entertained ... they think the show is 30 minutes," Phil said.

And the individual fireworks? They're "characters."

A fireworks show over Saks Fifth Avenue in New York City. Photo via Fireworks by Grucci/Facebook, used with permission.

"If you envision a stage, and you envision a blank script, the characters that are going to perform on that stage, in the form of choreography and dance, if you will, are the fireworks," he explained.

With each new performance, there's new fireworks technology for the team to learn.

"Recently, we developed another type of shell with a microchip built inside of it," Phil said.

While a traditional shell can explode up to a half-second off from the desired time, Phil explained that the detonation of a microchipped shell is predictable down to the millisecond.

"You can control where you can place a dot in the sky, at what elevation."

Each of these miniature dots, or "pencil bursts," creates a single dot. Connect 1,000 or more, and you can create fascinating, abstract designs in the sky, like the 600-foot high American flag the Grucci team created for a show commemorating the 200th anniversary of "The Star-Spangled Banner."

The American-flag effect. Photo via Fireworks by Grucci/Facebook, used with permission.

The company is also investing in ways to make its product more environmentally sound in order to remain sustainable for the long term, including biodegradable casings, smoke reduction, and removing certain chemicals from the manufacturing process.

"That's just as important as the aesthetic side," he said.

"I’m out in the water, so the service is a little sketchy."

Lauren Grucci is on the phone from a barge in the middle of Boston's Charles River. She's a member of the sixth generation of Gruccis to enter the family business.

Like her father, Phil, she's starting as a pyrotechnician, working with a team of 25 people to stage a show for an audience of an estimated half-million people.

A Grucci crew poses. Photo via Fireworks by Grucci/Facebook, used with permission.

"It’s a little hot out, but we were here last year, so we’re kind of familiar with it," Lauren told Upworthy.

For the ground teams, Fourth of July fireworks shows are like a gauntlet.

The shows are longer. The days are hotter. Everyone is out working. And there's little time to catch your breath.

"We’re out here all day, so it’s a lot of passion and a lot of stamina."

Each member of the team does a little of everything. They lift boxes. They set up the launch site with cranes. They hook up ordinance to computers.

"There’s a camaraderie that comes with it because you know that it’s kind of like a big family," Lauren said.

For Lauren, that includes her real-life family as well.

"There are some times when I’m on a show, and the pyrotechnicians are my uncles and my cousins and my brother and my friends," she said.

Phil Grucci (center) with family members. Photo via Fireworks by Grucci/Facebook, used with permission.

Working closely with her relatives has given Lauren some of her most treasured on-the-job memories — like the time she climbed the outside of a hop storage tower at Dublin's Guinness brewery to photograph a show with her cousin.

"We were kind of always raised to just do it; say 'yes,' and figure it out after."

It's a value, she explained that was instilled by her great-grandmother Concetta, who helped manage the shows when she was a baby.

Concetta Grucci and her husband, Felix, (far left) at the company's first factory. Photo via Fireworks by Grucci, used with permission.

"She was at every event, talking to whoever, whenever on stage. She just had a really great spirit and had a really great attitude about everything," Lauren said.

She thinks about her every time she launches a "gold willow" firework.

A golden "weeping willow" firework. Photo by Epic Fireworks/Flickr.

"That was her favorite shell, and it reminds me a lot of her."

Both technical know-how — and passion for the work — are passed down through the generations in the Grucci family.

"As a 6-year-old, I’d go out on the barge with my dad, and it was the coolest thing in the world to be out there with the guys and setting up the fireworks show," Phil said.

Too young to sail out with the boat, he would hang out on shore with his grandfather, watching his dad set them off from the barge.

"People that would come up to him and congratulate him and give him great wishes and congratulations, and that’s how I got hooked," Phil said.

He explained that his grandfather encouraged him to embrace change — atypical for the patriarch of a long-running family business.

Phil's grandfather, Felix Grucci, Sr. Photo via Fireworks by Grucci, used with permission.

"He began with shooting fireworks and lighting them with a cigar or a very tightly wrapped burlap bag," Phil said.

Of course, things are ... a little different these days.

"Now we’re shooting and displaying our fireworks with laptop computers."

He said he hopes his children and nephews will continue to embrace new technology as they move into leadership roles.

Perhaps most importantly, Phil hopes that — no matter what technological changes come along in the next 10 to 20 years — fireworks audiences continue to enjoy the show, blissfully unaware of the elaborate, frenetic ballet happening behind the scenes.

So if you spend this Fourth of July on a beach blanket, eating your soft-serve, not worrying about how the fireworks exploding above your head got there, that's by design.

Photo via Fireworks by Grucci/Facebook, used with permission.

As long as you leave wanting just a little bit more, Phil considers his job done.

"For me, that’s what the thrill is about. That’s what keeps you here at 2:30 in the morning and back in here by 8 the next morning to keep the machine going."

Potted plants and herbs can thrive in a container garden.

Potted plants and herbs can thrive in a container garden. Freshly harvested potatoes are so satisfying.

Freshly harvested potatoes are so satisfying. Do you see a box or do you see a planter?

Do you see a box or do you see a planter? Season 3 Dancing GIF by Party Down

Season 3 Dancing GIF by Party Down music video happy dance GIF by Apple Music

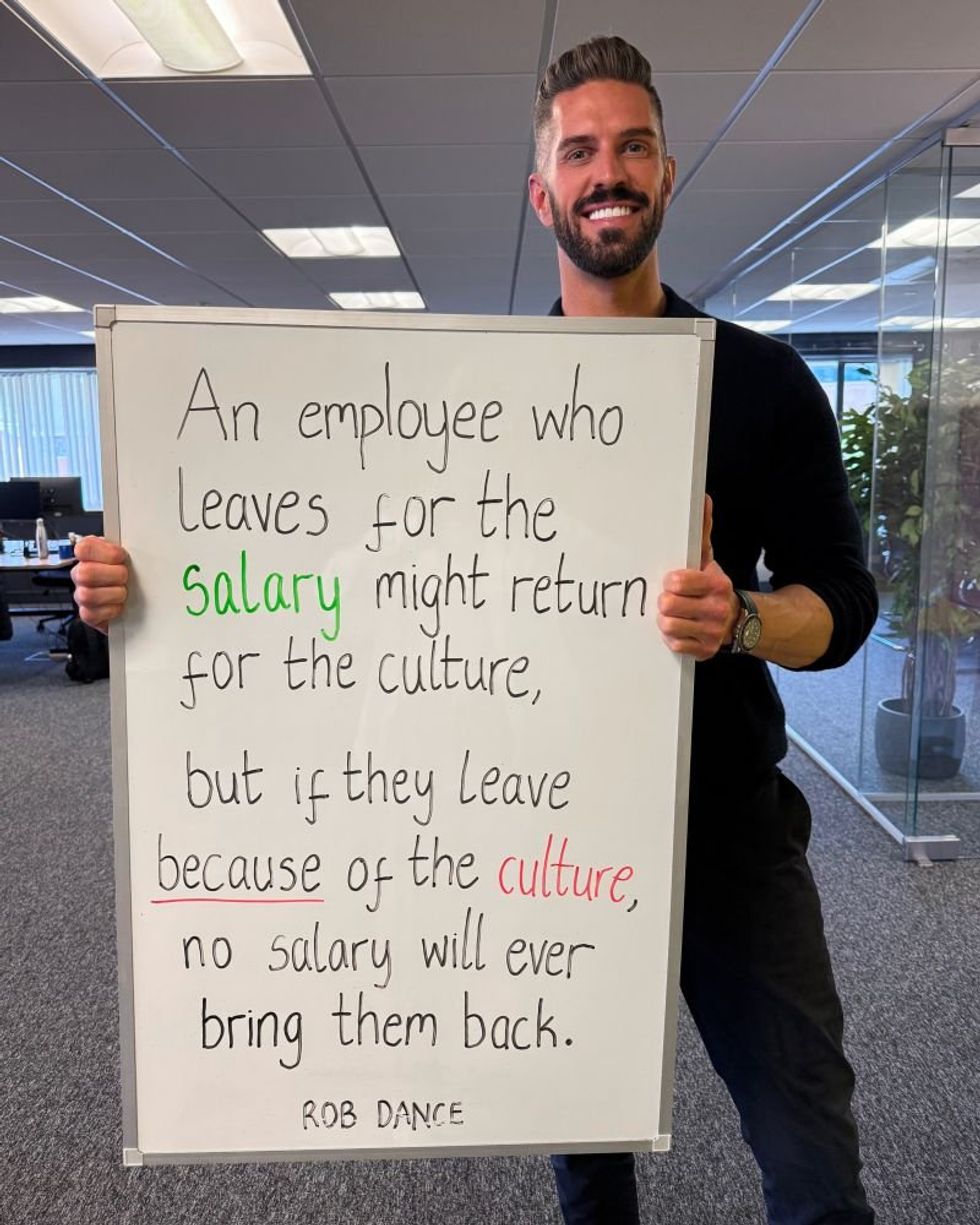

music video happy dance GIF by Apple Music CEO Rob Dance holds up a whipe board with his culture philosophy.

CEO Rob Dance holds up a whipe board with his culture philosophy.  Sometimes parents do understand.Image via Canva.

Sometimes parents do understand.Image via Canva. Shariya and the triplets.via

Shariya and the triplets.via  Shariya and the triplets.via

Shariya and the triplets.via