This 11-year-old U.S. citizen has been separated from her asylum-seeking mom for 222 days.

11-year-old Yeisvi Carrillo, an American citizen, has been in foster care for more than 220 days after being forcibly separated from her mother at the border.

Vilma Carrillo and her husband were living in Georgia in 2006 when Vilma gave birth to their daughter, Yeisvi. They lived there for about a year as undocumented farm workers in onion fields and warehouses before returning to their home country of Guatemala to care for Carrillo’s ailing mother in 2007.

A few years later, Carrillo’s husband grew violent. Carrillo was brutally abused, burned and beaten with increasing intensity, to the point that Yeisvi worried that her dad might kill her mom. That’s when Carrillo decided to return to the U.S. with her daughter and seek asylum.

In an interview with Upworthy, Shana Tabak, Executive Director of the Tahirih Justice Center in Atlanta, the legal non-profit who is representing Carrillo in immigration court, describes Carrillo's abuse as "severe." “Her four front teeth were punched out by her abuser,” Tabak says. “She was pulled by her hair, naked, wearing her underwear. Years of this. She finally decided that she feared too much for her life to stay.”

In May, Vilma and Yeisvi crossed the border in Arizona and requested asylum. That’s when they were forcibly separated.

Within 15 minutes of being held, border officials recognized that the 11-year-old Yeisvi was a U.S. citizen. They called in officials from the state of Arizona and told them that they couldn’t detain the girl because of her citizen status.

“They had Vilma sign papers relinquishing her custody of her daughter for 90 days,” says Tabak. “Vilma did not understand what she was signing because she does not read or write in any language. She’s an indigenous Mam speaker, who at the time spoke very little Spanish and no English.”

Then her daughter was torn from her, Tabak says. “She was crying and screaming so much that Vilma fainted and lost consciousness, and when she woke up her daughter was gone.” Yeisvi was put into foster care and Vilma was transferred to Irwin Detention Center in Atlanta.

It’s now been more than six months since the mother and daughter have seen one another.

In a cruel twist, Carrillo was flown to Texas for reunification in July, when the government was required to reunite separated families. Then she was told, “No, not you.”

As if being separated from your child by half a continent isn’t painful enough, Carrillo briefly thought that she and Yeisvi were going to be reunited when a judge ruled that families who had been subject to the government’s policy of detaining children separately from their parents must be reunited by July 26, 2018.

“In advance of the July deadline the authorities thought that she was qualified for reunification,” says Tabak. “So she and nine of her friends here from the Irwin Detention Center were taken to Texas to be reunited with their daughters. One by one, she watched them all be reunified. She kept asking, 'What about me? What about my daughter?' and they said, 'No, not you,' and then they sent her back here.”

Carrillo went to court without an attorney, without an interpreter who could understand her, and without the asylum documents that had been prepared for her by an attorney. Those documents were in a backpack when she was transferred back to Georgia from Texas, and she wasn’t allowed access to that backpack in time for her hearing. She said, on the record, “I don’t understand what’s happening and I don’t have my documents,” but the judge denied her asylum petition. That denial has been appealed by Tahirih Justice Center lawyers.

Carrillo’s lawyers also submitted a request for humanitarian parole for her so she could be released and reunited with her daughter, says Tabak. But the ICE director in the Atlanta field office refused.

Tabak explains that the federal government has the discretion to release her during the appeals process; they're simply choosing not to.

"Vilma has no criminal history, so she is not subject to mandatory detention. So under the law, Vilma is being held at the discretion of the federal government. That’s why we submitted a request for humanitarian parole. That’s why we applied for bond. Because these are decision points where the federal government, if it were doing its job properly, would evaluate the evidence and make a decision as to whether or not she should stay, and provide an individualized determination of—if they decided to hold her—why they will hold her. But in this case, we are getting no explanation as to why they are holding her. They’re just holding her.”

Carrillo's lawyers have filed a habeas petition challenging the constitutionality of her detention.

Carrillo could be deported and her daughter could be made to stay in the U.S., basically forcing permanent family separation on both an asylum-seeking mother and an American citizen.

Earlier this year, the Trump administration adopted a new policy that says domestic violence generally can’t be used as grounds for asylum, which makes Carrillo’s case harder to appeal. She’s also in Atlanta, Georgia, which Tabak says is the worst place in the United States to be an undocumented immigrant.

“It’s known as an ‘asylum free’ zone,” Tabak says. “Across the country, any immigrant who finds themselves in court and applies for asylum has about a 43% chance of getting asylum. In Atlanta, they have a 2% chance. So this is a terrible place to be applying for asylum.”

Ironically, although the domestic violence Carrillo and her daughter fled from isn't eligible grounds for asylum, that same violence could result in the unthinkable—a permanent separation in which Carrillo could lose custody of her daughter. The courts could potentially decide that it's too unsafe to send Yeisvi—an American citizen—back to Guatemala, meaning she would have to stay in the U.S. in foster care.

There are many possible outcomes to this case. The state of Arizona, where Yeisvi is living, must do what's in the best interest of the child, but there's no way for Yeisvi to legally stay with her mother while she's in detention. As of now, Carrillo is in jeopardy of losing her parental rights completely, solely because ICE is choosing to keep her detained.

Temporary separation following domestic violence and a harrowing journey is traumatic enough. Taking an 11-year-old's mother away from her permanently when she's already been through so much would be outright cruel.

Carrillo's story is gaining national attention and prompting celebrity advocacy.

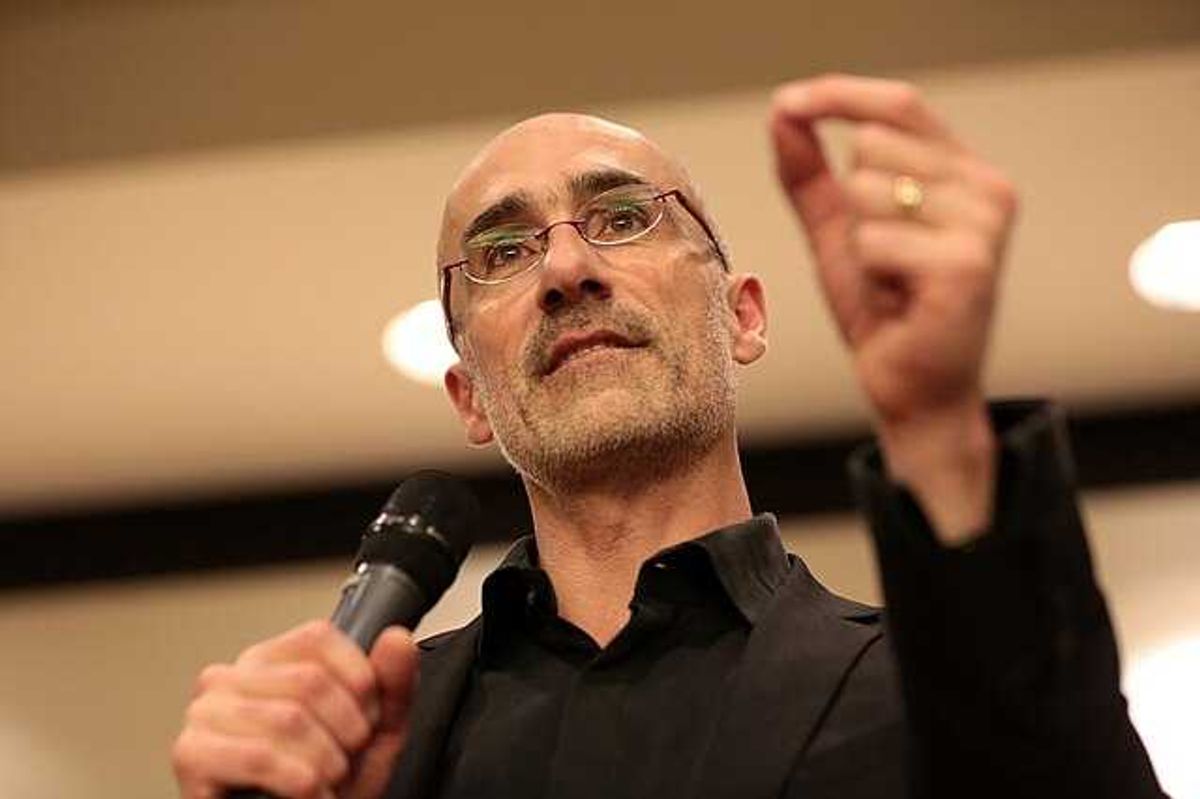

Penn Badgley, an actor and musician best known for his roles on CW's "Gossip Girl" and the Lifetime-turned-Netflix show "You," has taken an active role in Tahirih Justice Center's advocacy work. He accompanied Tabak on a visit to Carrillo at the Irwin Detention Center on December 14.

"I expressly do not believe that every problem is made better by adding a celebrity," Badgley told Upworthy in an interview. He does, however, believe we all need to use our voices to speak up for justice and to elevate the voices of those who are being harmed by our laws and policies. He says:

“There are a lot of really hard-working and intelligent people who are hitting the books to figure out, okay, where is the legal justification for this treatment of other human beings? They’re seeking asylum. It stands to be repeated, that is not a crime. If anything, they’re victims of crime before they come here. They’re seeking safety. They’re seeking refuge. These are fundamental principles this country is supposed to have been founded on...Our country claims to be a beacon of hope and light and justice in the world, and yet we have many stains on our historical record. These are deep, blood-red stains. If we want to be Americans, which ones do we want to be?"

Badgley says that instead of devolving into talking points, there are some fundamental questions that we as Americans need to be asking ourselves:

"What do these borders mean? What do they mean if they inflict criminal abuse upon people fleeing criminal abuse? If reaching our borders is bringing the same kind of harm or abuse to human beings fleeing abuse, what are we doing? What do these borders mean? What are we trying to protect? If we’re trying to protect our integrity as a nation, we actually might be doing a great job of undermining our integrity."

Badgley has used his social media accounts to help advocate for Vilma Carrillo and her daughter, sharing a petition to tell ICE to release Carrillo and reunite her with Yeisvi.

Carrillo's story is unique, but it highlights problematic policies and attitudes toward immigration and asylum.

Tabak says she's seen a shift during her career in immigration and human rights law, which has resulted in some unprecedented actions on behalf of the U.S. government.

“The federal government has been trying to erect a border wall to prevent people from seeking the asylum that they are entitled to under the law,” says Tabak. “Short of getting the permission from Congress to erect a physical wall, the government is doing everything it can to erect a legal wall for clients who are trying to access protection under the law.”

Tabak also points out some of the issues that make the asylum process harder for people like Vilma Carrillo:

“The issues that we’ve seen for a long time in Georgia are the issues that are now relevant across the country. We’re seeing failures of due process, like in Vilma’s case. We’re seeing judges with pronounced and overt bias against our clients. We’re seeing disregard for expert testimony on mental health and trauma. And those are phenomena that have existed in the Atlanta courts for many many years and currently we’re seeing that spread across the country. In addition, I think that some of the choices that the current federal government has taken are simply unprecedented. The choice to separate parents from children as a deterrent, it was contemplated under previous governments, but it was never carried out. That simply is unprecedented. It is in clear violation of international law."

Advocates for Carrillo hope to get a hearing to reunite Vilma and Yeisvi by Yeisvi's 12th birthday on December 20. Here are ways everyone can help:

Join those calling for Vilma and Yeisvi's reunification by signing and sharing this Change.org petition. Make a donation to support the work of Tahirih Justice Center or other non-profits that help represent immigrant families in court. And finally, use your civic voice to remind the U.S. government that asylum is a legal human right and that #familiesbelongtogether.

Many people make bucket lists of things they want in life.

Many people make bucket lists of things they want in life.

A boss giving an employee money.via

A boss giving an employee money.via

sipping modern family GIF

sipping modern family GIF

A distinguished chihuahua in a teal sweater

A distinguished chihuahua in a teal sweater