It's been four days since a group of armed men took over the headquarters of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge in Oregon on Jan. 2, 2016.

Ammon Bundy, leader of the armed occupiers at Oregon's Malheur National Wildlife Refuge. Photo by George Frey/Getty Images News.

Ostensibly, their cause is defending two ranchers who were sentenced to prison for burning 130 acres of the refuge, calling the conviction a governmental interference on the "people's constitutional rights."

Coverage of the standoff has mostly focused on the fact that these men have guns, that they're anti-government, that Ammon Bundy's father Cliven was in a similar standoff last year, that people are calling the group #yallqaeda, and that a group of armed #BlackLivesMatter protesters taking over a government building certainly wouldn't be called "peaceful." Given our national current preoccupation with mass shootings, terrorist attacks, and anti-government presidential candidates, this coverage is understandable.

But it's worth looking at what's really at stake here.

With all the attention on the armed ranchers, few people are talking about the birds and other creatures that the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge protects.

"When you look at migratory birds and how they use the landscape, Malheur National Wildlife is critically important," says Bob Sallinger, conservation director at the Audubon Society of Portland, which promotes education and conservation around bird populations at refuges like Malheur.

A burrowing owl at the Malheur National Wildlife Sanctuary. Photo by Candace Larson/Audubon Society of Portland, used with permission.

According to Sallinger, Malheur is home to the largest sandhill crane population of any refuge in the western United States.

20,000 white-faced ibises — 20% of the world's white-faced ibis population — live there as do 4,000 white pelicans and 7,000 grebes among hundreds of thousands migrating waterfowl and tens of thousands of shore birds.

For these birds, the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge is an essential stop along their migratory journey.

The Malheur National Wildlife Refuge is home to thousands of grebes like this horned one. Photo by Candace Larson/Audubon Society of Portland, used with permission.

In fact, Sallinger calls Malheur the "crown jewel" of the United States' wildlife refuge system.

Malheur is one of the first wildlife refuges in the western United States, created by President Theodore Roosevelt after Audubon Society founder William Finley persuaded him to set aside the land by showing him breathtaking photos of the habitat's bird population.

Many of the bird photos interspersed in this article were taken by Finley in 1908, the year that Roosevelt created Malheur.

Photos like this one of a great horned owl:

The great horned owl is one of many species of birds threatened by the occupation of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge. Photo by William Finley and Herman Bohlman/Audubon Society of Portland/U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service National Digital Library.

And this photo of a lone white-faced ibis:

Portland Audubon Society founder William Finley's 1908 photo of a white-faced ibis at Malheur National Wildlife Refuge. Photo by William Finley and Herman Bohlman/Audubon Society of Portland/U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service National Digital Library.

And this glorious photo of a pod of American white pelicans:

Malheur National Wildlife refuge is an essential stop along many bird populations' migratory journey, including that of the American white pelican. Photo by William Finley and Herman Bohlman/Audubon Society of Portland/U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service National Digital Library.

And this hand-painted glass slide of a northern pintail:

Photo by William Finley and Herman Bohlman/Audubon Society of Portland/U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service National Digital Library.

As well as this delicate yellow-headed blackbird:

Photo by William Finley and Herman Bohlman/Audubon Society of Portland/U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service National Digital Library.

And this handsome mallard:

Photo by William Finley and Herman Bohlman/Audubon Society of Portland/U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service National Digital Library.

It's thanks to Roosevelt setting a precedent for creating protective refuges like Malheur that America retains so much of its wildlife — fowl and fauna and mammalian and reptilian alike.

Sallinger says he doesn't know if the armed occupation will cause immediate harm to the animals on the refuge, but he is worried about the long term impact.

"[The armed ranchers' occupation will] take very thin resources and stretch them even thinner now," Sallinger says. The refuge has a tight schedule and very limited staffing resources to get all the restoration, monitoring, and management tasks that they need to get done during the year.

Malheur Lake bird nest. Photo by William Finley and Herman Bolhman/Audubon Society of Portland/U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service National Digital Library.

This includes monitoring where various bird populations nest, the effect their management strategies have on the birds, and cutting-edge techniques to get rid of an invasive carp species in Malheur Lake to allow more birds to breed there. So far, these invasive carp have eaten everything in sight in the lake and have stirred up so much sediment that sunlight can't get through to create essential food sources and allow habitat features to grow back.

Any delay in this work makes Malheur employees' jobs harder and could mean long-term harm to the wildlife in the refuge.

The occupation could also undermine the amount of work environmental groups have done to involve the community in protecting wildlife.

In 2013, the refuge brought together a coalition committed to Malheur's restoration.

Sallinger says that when he talks about shining examples of collaborative projects, he talks about Malheur first.

The coalition behind the Malheur Wildlife National Refuge wants to restore Malheur Lake as a viable habitat for the various bird populations that frequent it. Photo by William Finley and Herman Bohlman/Audubon Society of Portland/U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service National Digital Library.

As a result, it makes him sad that the Malheur occupiers are trying to portray the relationship between the refuge and the surrounding community as one of conflict.

"The truth there is that the refuge has been working very diligently to include the community," he says.

In fact, bird watchers at the Daily Kos have a message from the bird-watching community for those who have engaged in poaching and other harmful activities around various wildlife refuges, writing:

"Malheur, Hart Mountain, Klamath Marsh, Yellowstone, Glacier, Yosemite etc etc, they all belong to us, we the American people, and no small group of armed thugs is going to destroy the great wildlife and national park system that our great Republican President Teddy Roosevelt and John Muir put in place over a century ago."

The ranchers claims to be working in the interest of the people, but it's worth noting the people don't want them there.

In its press release, the Portland Audubon Society highlights this fact (emphasis added):

"The occupation of Malheur by armed, out of state militia groups puts one of America’s most important wildlife refuges at risk. It violates the most basic principles of the Public Trust Doctrine and holds hostage public lands and public resources to serve the very narrow political agenda of the occupiers. The occupiers have used the flimsiest of pretexts to justify their actions—the conviction of two local ranchers in a case involving arson and poaching on public lands. Notably, neither the local community or the individuals convicted have requested or endorsed the occupation or the assistance of militia groups."

Occupation leader Ammon Bundy told CNN that the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge is "destructive to the people of the county and to the people of the area." But what these anti-government protesters who seek to make federally protected lands available for hunters, farmers, and anyone who wishes to claim them forget is that wildlife refuges exist to protect the environment not only for wildlife, but for people as well.

It's thanks to national wildlife refuges that we have clean water and clean air.

On Tuesday, Jan. 6, the third day of the occupation, it was reported that the people of the nearby community of Burns, Oregon, were hoping that the uninvited, armed occupiers will leave. They don't want them there, and the two ranchers who were convicted of arson don't want them there either.

For the sake of the animals on the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge, and for the people who help them, let's hope so.

Millennial mom struggles to organize her son's room.Image via Canva/fotostorm

Millennial mom struggles to organize her son's room.Image via Canva/fotostorm Boomer grandparents have a video call with grandkids.Image via Canva/Tima Miroshnichenko

Boomer grandparents have a video call with grandkids.Image via Canva/Tima Miroshnichenko

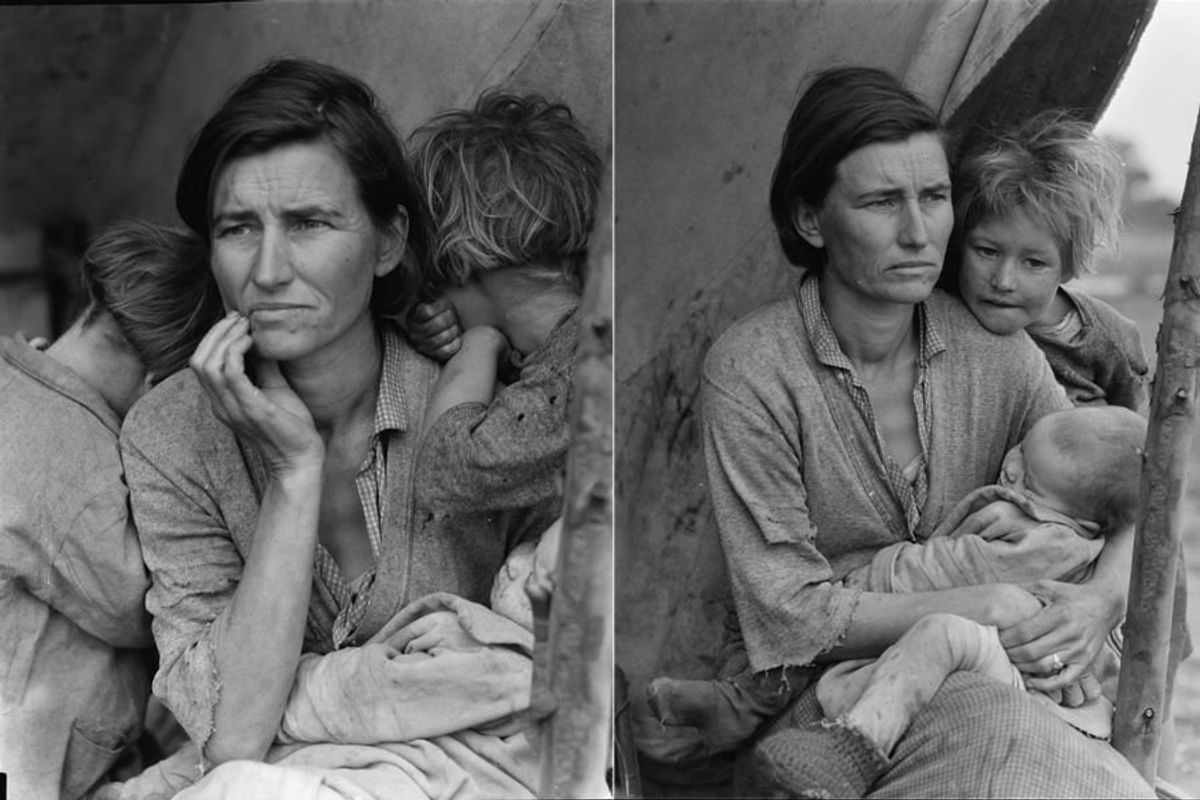

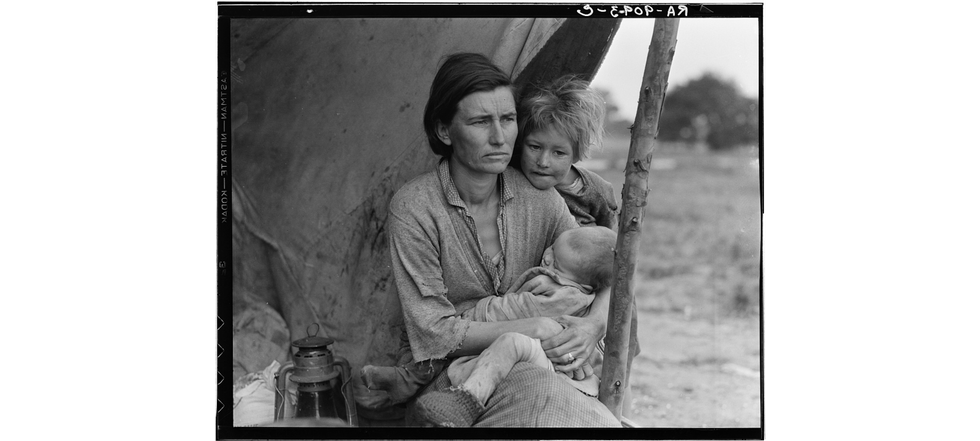

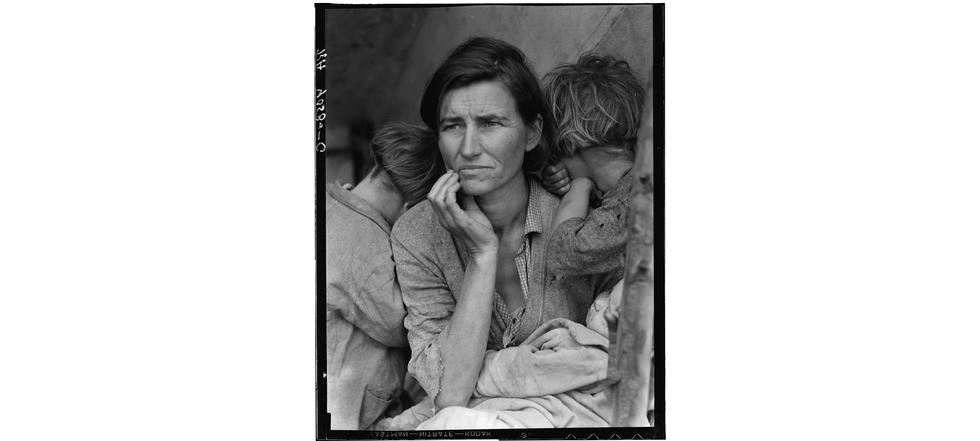

Worried mother and children during the Great Depression era. Photo by Dorthea Lange via Library of Congress

Worried mother and children during the Great Depression era. Photo by Dorthea Lange via Library of Congress  A mother reflects with her children during the Great Depression. Photo by Dorthea Lange via Library of Congress

A mother reflects with her children during the Great Depression. Photo by Dorthea Lange via Library of Congress  Families on the move suffered enormous hardships during The Great Depression.Photo by Dorthea Lange via Library of Congress

Families on the move suffered enormous hardships during The Great Depression.Photo by Dorthea Lange via Library of Congress

A couple cooking in the kitchen with a cat sitting on the table beside chopped ingredients.

A couple cooking in the kitchen with a cat sitting on the table beside chopped ingredients.