People claim the soil from this Irish churchyard has healing properties and it turns out they're right

Scientists discovered it isn't just a myth.

The soil in an Irish churchyard has proven healing properties

We’ve all heard an old wives tale—a superstition or belief that seems ridiculous but just might have a kernel of truth to it. For instance: An apple a day keeps the doctor away? Probably not literally true, but there’s no question that good nutrition helps keep you from getting sick. Counting sheep will help you fall asleep?

Well, it might, for some people. In other words, old wives tales might not be true for everyone all the time, but there’s often a little bit of truth in there somewhere. For centuries, the people of northern Ireland had an old wives tale of their own: A small churchyard in a hamlet called Boho has soil that is rumored to have magical healing powers.

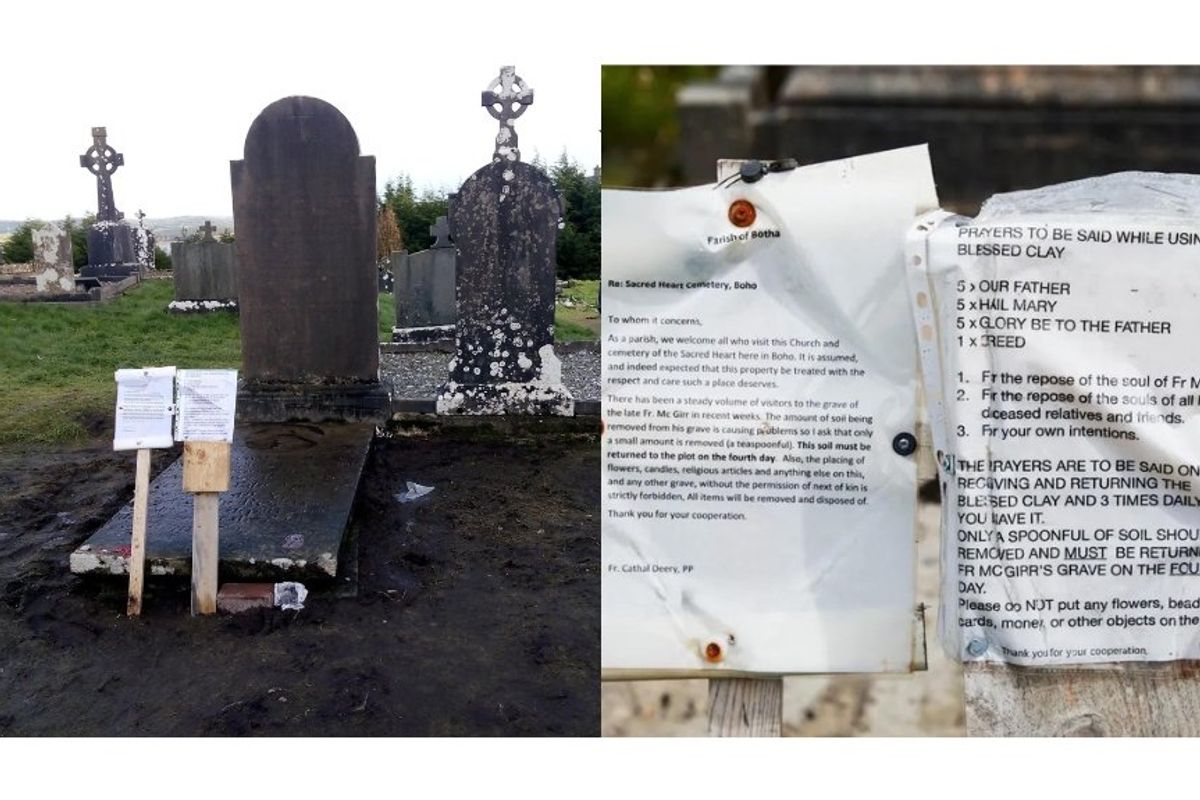

A picture of the Boho Church of Ireland Churchyard in County Fermanagh. Found on the Church’s facebook page.

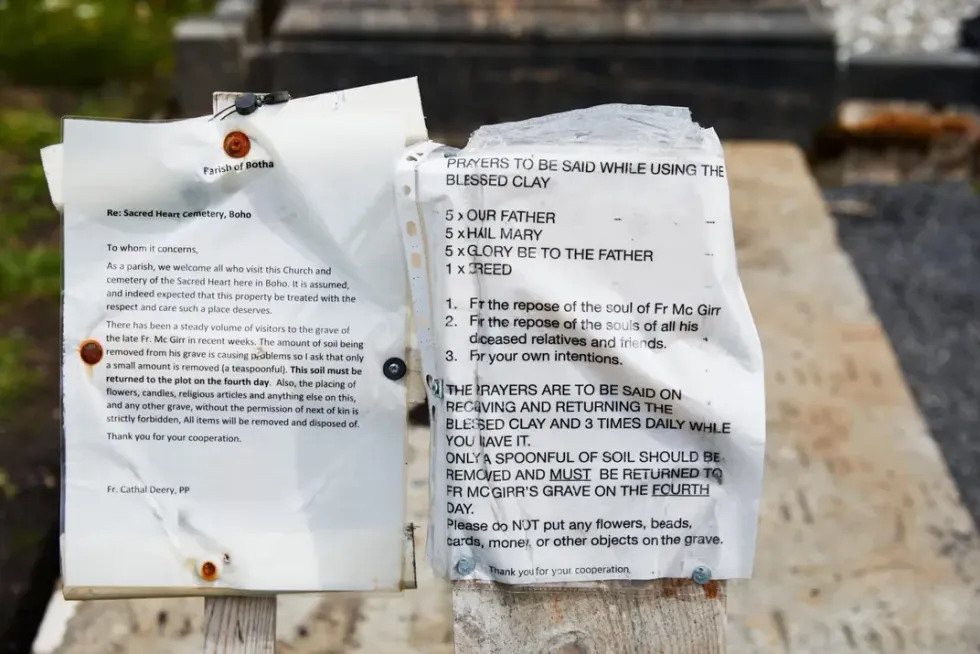

According to legend, in 1815, a local folk healer named Reverend James McGirr supposedly said on his death bed that “the clay that covers me will be able to cure anything that I was able to cure when I was with you when I was still alive.” After the reverend died and was buried, parishioners started traveling to his gravesite in the churchyard to sample the “clay” (aka, the soil) from his grave.

The local custom went like this: A person would kneel beside McGirr’s grave and collect a “thumbnail size patch of dirt,” likely no more than a teaspoon or two, and put it into a small cotton pouch. After that, the person would take the soil home (being careful not to speak to anyone on the way home, since it would interfere somehow with the healing) and place it under the pillow of the person who was sick. After placing the pouch under the pillow, that person was required to say prayers for the person who was sick, as well as for the soul of Father McGirr and all of his deceased relatives and friends, along with a few other Catholic prayers for good measure.

Within a few days, the sick person would supposedly be cured, and the dirt would be returned to the churchyard and placed back on McGirr’s grave. (Failure to return the soil within four days meant bad luck and that your healing wouldn’t be granted.) For centuries, the soil was used to heal flesh wounds, toothaches, sore throats, and more—and according to legend, it actually worked.

Microbiologist Gerry Quinn, who grew up near Boho, had heard the old wives tale throughout his childhood. As a researcher at Swansea University Medical School in 2018, he decided to dig into the old wives tale and find out the truth about the soil once and for all. Was it purely superstition, or could the soil somehow really be healing people?

“There seemed to be a lot of superstition around [this folk remedy], but in the back of my head I realized that there's always something behind these traditions or they wouldn't be going on so long,” Quinn said in an interview.

Quinn and his colleagues collected soil samples from McGirr’s grave and the surrounding churchyard and found something surprising: The soil contained Streptomyces, a bacteria that’s found in highly alkaline environments and is responsible for producing about two-thirds of all the antibiotics we currently use. Streptomycin, for instance, which is derived from Streptomyces, is one of the few antibiotics that can treat tuberculosis.

In just a small sample of the churchyard soil, the researchers were able to isolate eight different strains of Streptomyces, which could potentially produce hundreds of different antibiotics. But wait—there’s more. One of the strains, the researchers discovered, had never been previously identified, and that’s great news for scientists (and, frankly, for the rest of the world).

Antibiotics have revolutionized medicine, saving millions of lives every year and preventing an untold number of infections. Unfortunately, antibiotics have also been overused, which leads to something called antimicrobial resistance. This is when bacteria mutate and become harder to kill, eventually becoming “superbugs” that are resistant to antibiotics altogether. The more resistant the bacteria, the more infections become impossible to treat—and this leads to more disease, disability, and death. Antimicrobial resistance is one of the world’s leading health problems, according to the World Health Organization.

And this is exactly what makes the discovery in Boho so important. When the Swansea researchers tested the never-before-seen strain of Streptomyces, they discovered it was able to kill four of the top six multi-resistant bacteria that are responsible for most healthcare-related infections, such as MRSA.

“Our discovery is an important step forward in the fight against antibiotic resistance,” wrote Quinn and Swansea microbiologist Paul Dyson in an article in Newsweek. “The discovery of antimicrobial substances … will help in our search for new drugs to treat multi-resistant bacteria, the cause of many dangerous and lethal infections.” The Swansea team is currently identifying strains of bacteria from the soil and testing them against other multi-resistant pathogens.

Lesson learned: Sometimes old wives tales aren’t “tales” at all—they can actually save lives.

A woman is getting angry at her coworker.via

A woman is getting angry at her coworker.via  A man with tape over his mouth.via

A man with tape over his mouth.via  A husband is angry with his wife. via

A husband is angry with his wife. via

Curling requires more athleticism than it first appears.

Curling requires more athleticism than it first appears.

a man sitting at a desk with his head on his arms Photo by

a man sitting at a desk with his head on his arms Photo by  Can a warm cup of tea help you sleep better? If you believe it, then yes. Photo by

Can a warm cup of tea help you sleep better? If you believe it, then yes. Photo by

Comfort in a hug: a shared moment of empathy and support.

Comfort in a hug: a shared moment of empathy and support. A comforting hug during an emotional moment.

A comforting hug during an emotional moment. Woman seated against brick wall, covering ears with hands.

Woman seated against brick wall, covering ears with hands.