Breathtaking clip resurfaces of a 16-year-old 'waitress' Ariana Grande singing in a Chili's

"Yes. It's really her."

A resurface click of a 16-year-old Ariana Grande

Before she was Glinda the Good Witch, before she was a Grammy-winning music sensation, Ariana Grande-Butera was just a girl from Florida with huge dreams. After a quick stint in a Broadway musical, by the age of 15, she was part of the Nickelodeon world, beloved for her role as Cat Valentine in Victorious and it's spin-off Sam & Cat.

After a lot of hard work debuting her first album, the rest is history. But every so often, a picture or video of a teenage Ariana makes the rounds, and the internet goes wild. This time, Facebook, Instagram, and TikTok have revived an old clip of a 16-year-old Ariana singing "Happy Birthday" to customers at a Chili's restaurant.

This isn't the first, nor probably the last, time the algorithms have popped this one up to the surface, especially since Ariana is on fire right now. But the fans and comments continue to discuss—with passion—how much they love her, even beyond her latest Wicked sensation.

What's interesting is that many fans still get the whole premise of it wrong. In a clip posted on TikTok, it's described as "Ariana singing happy birthday when she was a waitress at Chili's," then adding, "it's giving Meena vibes" (a reference to a shy performer in the animated film Sing, voiced by Tori Kelly).

@cloud_ari3 it's giving Meena #fyp #foryoupage #arianagrande #arianator #viral #cloud_ari3

There are over 300,000 likes and thousands of comments, with many questioning the original post. One writes, "She was working as a waitress while working on the set of Victorious?? Cuz she didn’t have red hair till the producers made her dye it." Others agree and wonder why she's there, clad in an apron and a tank top.

Some swear they knew her while she worked at the restaurant. "No one believed me that she worked at Chili’s. I remember her photos working there!"

And some are just impressed by both Grande AND Chili's. "Of COURSE Ari would work somewhere as magical as Chili's."

Finally, enough comments reveal that no, she was not, in fact, a working actress, raising money for a St. Jude charity event. "Y'all, she was already semi-famous when she did this. She worked one day as a guest server for a St. Jude Children's Hospital fundraiser."

In fact, that very fundraiser was a Chili's-based campaign called "Create-A-Pepper," whose goal was to raise $50 million for St. Jude Children's Hospital. On Popstar! Magazine's YouTube channel, Ariana shares, "If you donate a dollar or more, they can color in a pepper. The proceeds will go to St. Jude and help raise awareness for kids with cancer."

- YouTube, Popstar! Magazine, Ariana Grande www.youtube.com

In the video, Ariana also gives her heartfelt gratitude to another Chili's employee whom she says has been teaching her "how to be a waitress." The woman commends Ariana on her skills, though admits she doesn't quite know the menu. Ariana laughs and jokes that she's been making up things. "We have a sandwich with bananas and peanut butter and Nutella and fluff."

The Create-A-Pepper campaign is still very much active, and Chili's holds their donation drive every September.

- Kelly Clarkson and Ariana Grande's pop diva duel on Jimmy Fallon left people begging for more ›

- Ariana Grande just revealed she likes ‘women and men’ and refuses to ‘label’ her sexuality. ›

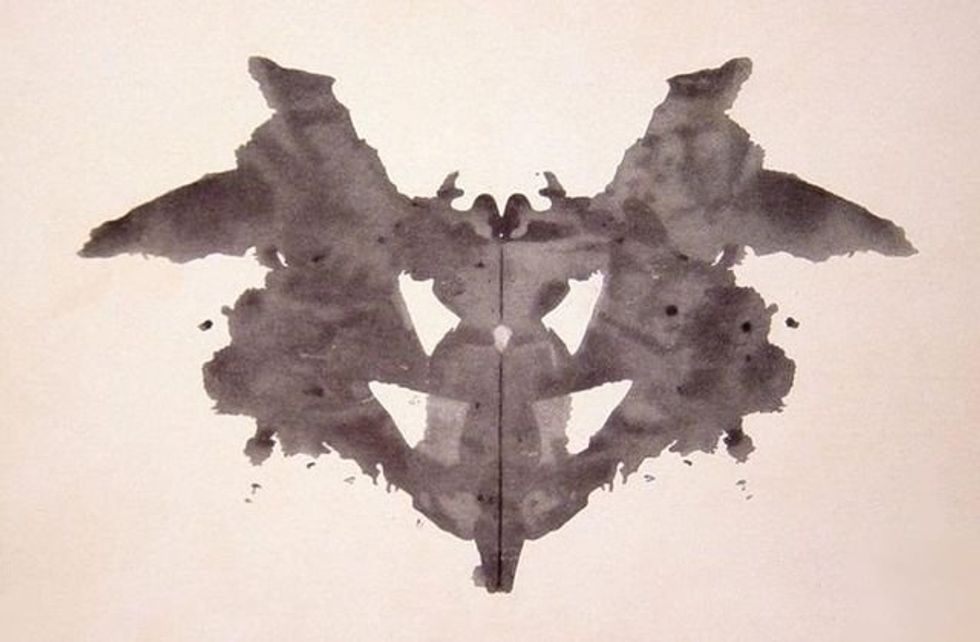

- 'Wicked' is becoming a political Rorschach test and so many people are missing the point ›

- Ariana Grande wows TikTok with a stunning, stripped down cover of 'Over The Rainbow' ›

- Ariana Grande says therapy should be 'mandatory' for all child stars ›

The first inkblot in the Rorschach test.Public domain

The first inkblot in the Rorschach test.Public domain