When people are ready to leave a relationship, many feel pressure to have a compelling reason. There are reasons that no one will disagree with, such as a partner's abuse, infidelity, or trouble getting along with family.

But what if you just aren’t feeling the relationship anymore, or don’t think they appreciate all you have to offer? Those can be perfectly fine reasons, too. It's totally fine to break up with someone over reasons that some may find trivial.

It’s your life; you can’t live it with your chosen people.

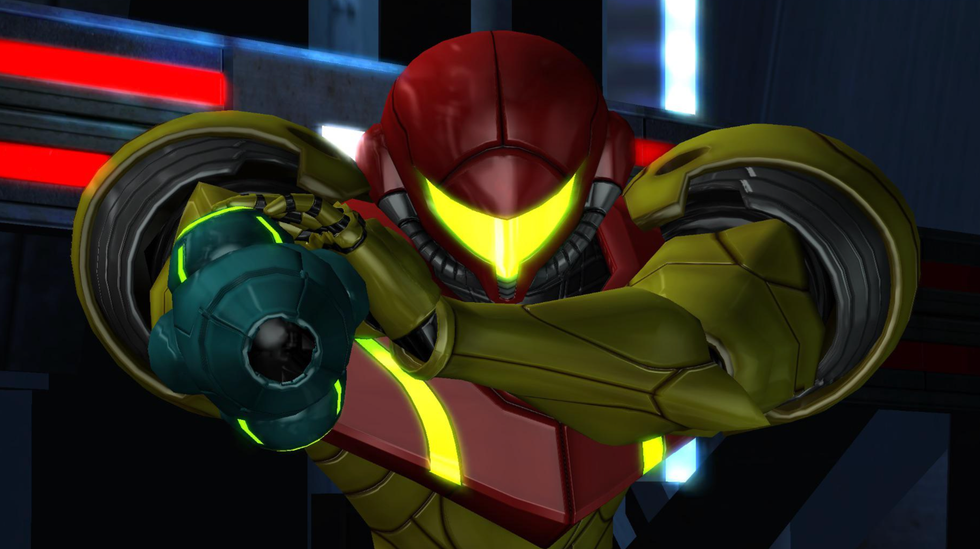

A Reddit user named Grand_Gate_8836 asked the AskWomen forum, “What is a very underrated reason for breaking up with your significant other?” and many women shared that they broke up with their partners because they just weren’t feeling the relationship. Others brought up reasons that people may not have had in the past, such as pornography addiction, immaturity and spending too much time playing video games.

On a deeper level, the discussion made many women who feel insecure about their reasons for leaving someone feel a lot better about following their hearts.

Here are 15 of the best “underrated” reasons for breaking up with one’s significant other.

1. Mental health

"I think bad mental health can be a big reason for splitting from someone. Nobody tells you how lonely it can get to be with someone who has mental health issues. It can take years for you to understand them and then eventually realize that you can’t help them until they choose to help themselves. This is due to severe unawareness around mental health issues I feel." — Grand_Gate8836

2. They don't find you attractive

"At the risk of sounding petty: they don't 100% love the way you look, even if they try to spin it in a positive way. I mean statements like 'she's not beautiful but I love her personality and sense of humor"'or 'she's a 5 on a good day but I guess so am I' or 'she's not what I'd consider my type but there's something about her.' I appreciate honesty as much as one can, but in my opinion, this is just depressing. Beauty comes in so many different shapes and forms. How can someone not find it in a person they claim to love? To me it basically means your SO is settling for you and will be forever comparing you to some kind of ideal you don't match." — JankyRobot42069

3. Not the outdoorsy-type

"I broke up with someone who had very conflicting interests and hobbies to mine and assumed I would just be on board with taking them up with him. I like the outdoors. I do not like devoting every weekend to hiking." — Justwannaread3

"Imo, this is so underrated. 'I enjoy X, but I do not enjoy devoting all of my free time to X.' is absolutely valid in and of itself. And leaving someone who doesn't grasp that is so much better for mental health in the long run." — DragonFlySunrise

4. Different goals

"You know, one thing that doesn't get talked about enough is having different life goals and values as a reason to break up with someone. It's not just about whether you both like the same movies or enjoy the same hobbies. It's about where you see yourself going in life and what you believe in. Imagine you're super into traveling the world and experiencing new cultures, but your partner is more about settling down in one place and building a stable career. It might not seem like a big deal at first, but over time, those differences can really start to wear on the relationship. You might find yourself feeling like you're not on the same page about the important stuff, like where you want to live or what you want to prioritize in life. So yeah, having different life goals and values might not be the most obvious reason to break up, but it can definitely be a deal-breaker if you're not aligned in those areas." — Good1Mufferaw

"It never ceases to amaze me that people ignore compatibility issues. It's the most important feature in a relationship. And marriages that continue regardless of how whack the lack of compatibility is." — Savagefluerelis23

5. You're not happy

"They're just not making you happy. You're just not happy with them, and you deep down feel you could be happier elsewhere either alone or with someone else. They're a good, kind person, a responsible adult, etc, but they're not "it" for you. This is often considered a trivial reason to end a relationship or marriage but it's such a BIG DEAL. You should want to be happy and should want them to be happy too! You know when you're not happy. This idea that you should only leave a partnership or friendship because of something deemed "more serious" doesn't feel right to me. One of the hardest things is walking away from someone who is not abusing you, is really good on paper but it just NOT doing it for you because society will always shame people and especially women for leaving because of unhappiness. That inkling feeling underneath of 'they might not be it for me,' we are taught to just not listen to ourselves." — The_Philosophied

6. Bros came first

"He prioritized his friends over me. I think prioritizing friends and family are important, but it got to a point where I was miserable. We were both mid-thirties, and he wanted to go to parties and bars all the time to see his friends. We never had quality time together. It reached its breaking point when my aunt suffered cardiac arrest and was airlifted from 700km away to the hospital in my city. Instead of coming to the hospital with me, or even emotionally supporting me when I went to be with her, he went to the bar and got drunk. I didn't even get a text or call for 24 hrs he just disappeared. When I got upset, he said, 'Seeing Dave is more important, he's my friend' I broke up with him the next day. My aunt died a few hours later." — MeatCat88

7. Pornography

"Porn addiction. Society has brainwashed people into thinking this is normal behavior." — 1989sBiggestFan13

"This is what killed my relationship with my ex-fiance after 7 years. I genuinely thought I was asexual -- nope. He just watched so much, such intense porn (even when I was putting out) that I stopped having any sexual interest at all." — Arwynn

8. Conspiracy theories

"There wasn’t an insane conspiracy theory this dude didn’t believe. ...The first one he told me: on our second date was around the time of the Miami Mall incident. He truly believed 8ft tall shadow aliens invaded the Miami Mall and the government was keeping hush about it. His further conspiracy was that the government was overrun by 'replaced people' basically aliens pretending to be people." — SinfullySInless

9. Video games

"Video games are far more important than spending time with their partner. I'm a very simple person. I don't care about gifts or having money spent on me. Let's go for a walk in the park, just spend some time with me. My ex-husband would find any excuse to not spend time with me. The most common was 'gas costs money, I'd rather hang out at home.' His idea of 'hanging out' was him playing video games with his online friends while I sat quietly watching TV, but with the volume super low so his friends wouldn't be 'distracted.' God forbid I laughed at all, he'd get so mad at me for it." — NatAttack89

10. Peter Pan syndrome

"Peter Pan syndrome. When my 60-year-old boyfriend told me (53F) the reason he had not 1 dollar saved for his retirement is because he is a 'risk taker' and I’m not, I realized I’d have to support him for the rest of his life while he looked down on me for it and walked away." — Slosee

11. Domestic burden imbalance

"Incompatible cleaning habits. Seems like an easy thing to remedy but in reality different standards of cleanliness will create an uneven burden of domestic labor for the partner with higher standards, or create a living environment in which that partner is uncomfortable, or create a situation where the partner with lower standards feels constantly berated/nagged to do something they don’t see as benefitting them in any way. I know multiple couples who broke up at or just before the 'moving in' stage for this reason, and I think it’s a super valid way to decide you’re not compatible in a long-term domestic relationship." — Angstyaspen

12. Stuck in a rut

"Disinterest in trying or experiencing new things and only sticking with what they know. If you’re someone who enjoys trying new restaurants, going to events, exploring new cultural experiences, etc and your partner is content to sit at home in their comfort zone, it eventually gets frustrating. I refused to date someone because of this mentality. If it wasn’t happening within a few miles of his house, he wasn’t terribly excited about doing it. Also, men who think basketball or gym shorts are acceptable casual attire." — Edjennersmilkmaid

13. Fell out of love

"Because you don’t love them anymore. I say this is an underrated reason because so many people think they need a catalyst event in order to justify breaking up. But if you’re not happy and the relationship isn’t fulfilling, that’s a solid enough reason." — Lydviciousss

14. Immaturity

"It felt like parenting. Like I was hanging out with a kid all the time. I was doing all the work, all the driving, all the planning. Like I was managing a child. 'This ain’t my job.'" — K19081985

15. Geographically undesirable

"Not agreeing on where you want to live. I've seen people start a relationship while one or both was living abroad, thinking 'We'll figure it out.' But actually building a life and having kids somewhere far from your own roots, or just in a place you don't really like, is a lot." — Princess Sophia Black