The forgotten link between Candy Land and polio and why it still matters

The history of the classic board game holds an important lesson about disease.

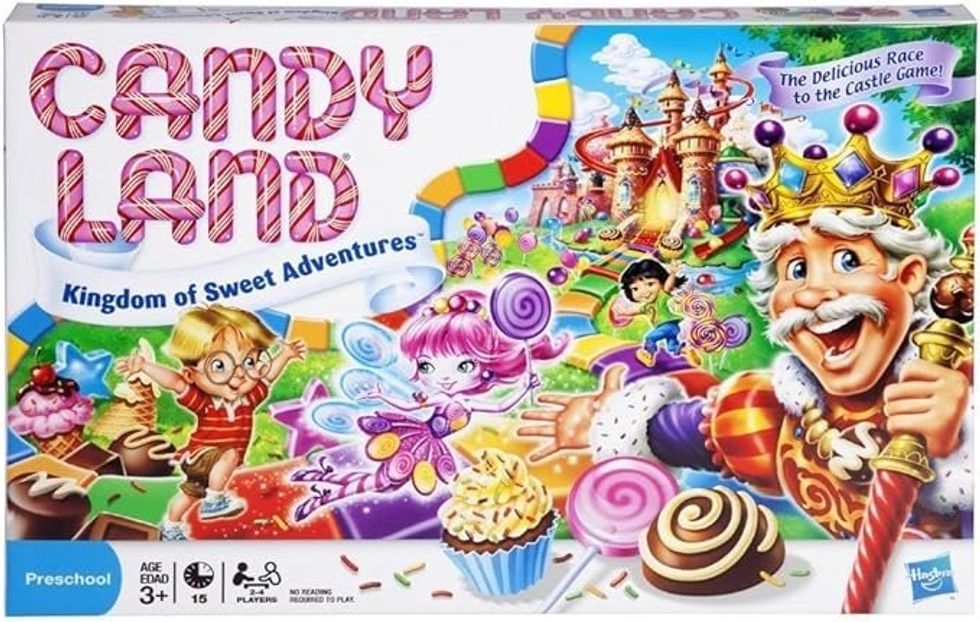

Candy Land was created for kids in the hospital with polio.

Candy Land has been adored by preschoolers, tolerated by older siblings, and dreaded by adults for generations. The simplicity of its play makes it perfect for young children, and the colorful candy-themed game has endured as an activity the whole family can do together.

Even for the grown-ups who find it mind-numbing to play, there's some sweet nostalgia in traversing the Peppermint Forest and avoiding the Molasses Swamp that tugs at us from our own childhoods. There are few things as innocent and innocuous as a game of Candy Land, but many of us may not know the dark reality behind how and why the game was invented in the first place.

Candy Land was invented by retired schoolteacher Eleanor Abbott while she recovered from polio in 1948. She was convalescing in a San Diego hospital surrounded by children being treated for the disease and saw how isolating and lonely it was for them. The game, which could be played alone and provided a fantasy world for sick children to escape to, become so popular among the hospital's young patients that Abbott's friends encouraged her to pitch it to game manufacturer Milton Bradley. The post-World-War-II timing turned out to be fortuitous.

“There was a huge market—it was parents who had kids and money to spend on them,” Christopher Bensch, Chief Curator at the National Toy Hall of Fame, told PBS. “A number of social and economic factors were coming together for [games] that were released in the [post-war era] that has kept them as evergreen classics." Candy Land soon became Milton Bradley's best-selling game.

Since the game doesn't require any reading or writing to play, children as young as 3 years old could enjoy it when they were feeling sad or homesick in the polio ward. As the polio epidemic ramped up in the early 1950s, the game gained even more popularity as parents often kept their kids indoors during polio outbreaks in their communities.

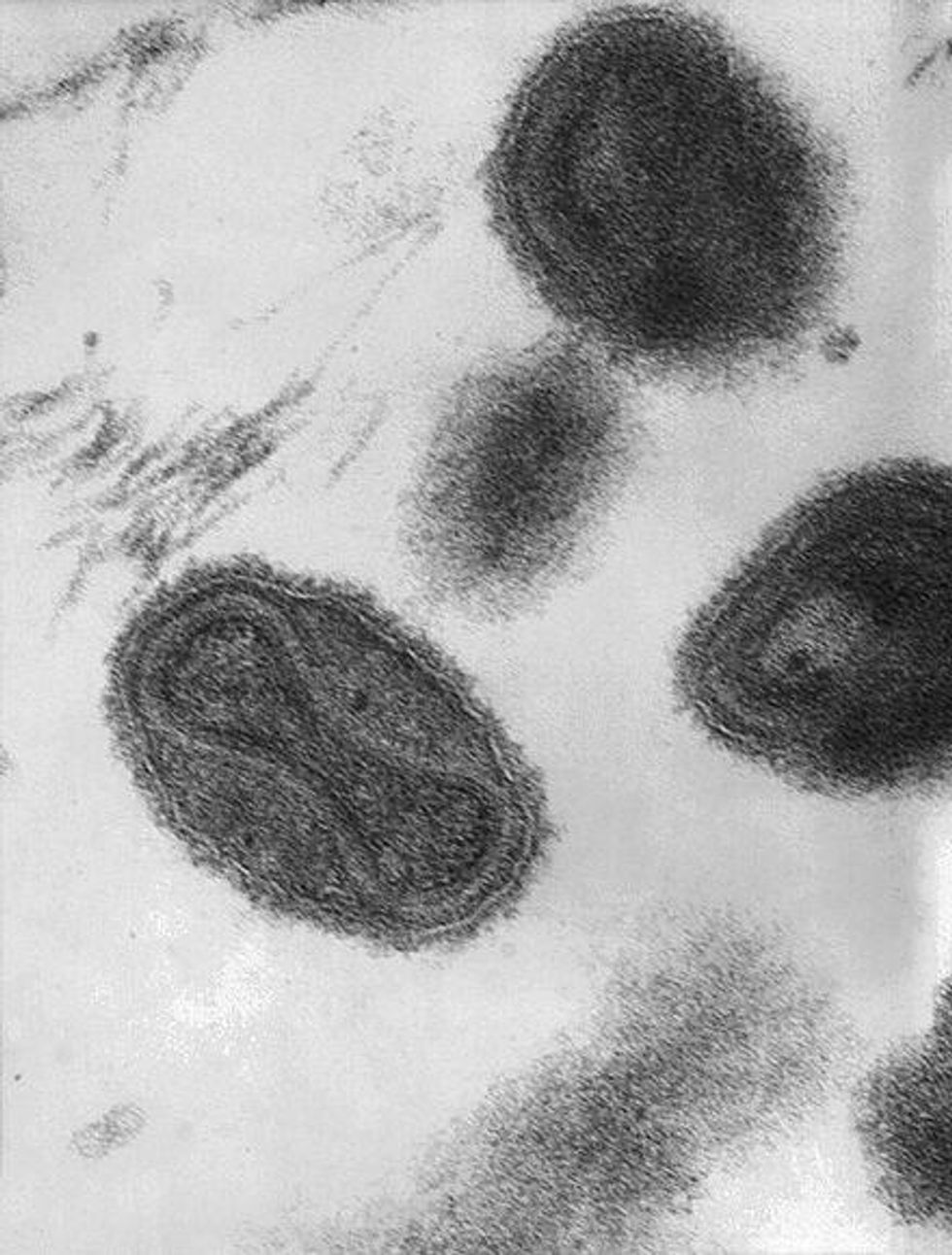

The polio vaccine changed the game—both for the disease and for Candy Land. Jonas Salk’s inactivated polio vaccine (IPV) was licensed in the spring of 1955 and a widespread vaccine campaign was launched. By 1961, polio cases had dropped from 58,000 to only 161. The disease was considered eradicated from the Americas in 1994, and, as of 2022, the only countries in the world to have any recorded cases were Pakistan and Afghanistan.

In the 70 years since the polio vaccine came out, Candy Land's connection to the disease has been lost, and it's now just a classic in the family board game cabinet. The fact that polio has so successfully been controlled and nearly eliminated makes it easy to forget that it used to be a devastating public health threat that spurred the need for the game in the first place. Children are routinely vaccinated for polio, keeping the disease at bay, but anti-vaccine messaging and fear threatens to impact the vaccination rates that have led to that success. Vaccination rates took a hit during the COVID-19 pandemic, and with the appointment of one of the most popular vaccine skeptics as the U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services, public health specialists are concerned.

There is no cure for polio, so the vaccine is by far our best weapon against it. According to infectious disease experts, it's not impossible for polio to make a comeback. “It’s pockets of the unimmunized that can bring diseases back," Patsy Stinchfield, former president of the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases, told Scientific American. "If you have a community of people geographically close to each other and they all choose not to vaccinate, that community immunity is going to drop quickly. And if a person who has polio or is shedding polio enters that community, the spread will be much more rapid.”

Without herd immunity, vulnerable people such as babies who are too young to be vaccinated and people with compromised immune systems are at risk in addition to the unvaccinated. And since up to 70% of polio cases are asymptomatic, there can be a lot more disease circulating than it appears when symptomatic disease is detected. No one wants the serious outcomes that can come with polio, such as paralysis, the inability to breathe without assistance, or death, especially when outbreaks are entirely preventable through vaccine-induced community immunity.

The fact that kids have been able to enjoy Candy Land for decades without thinking about polio at all is a testament to vaccine effectiveness, but it's also a reminder of how easy it is to take that carefreeness for granted.

Author Roald Dahl in 1954, before his daughter Olivia was born.

Author Roald Dahl in 1954, before his daughter Olivia was born. Measles often causes a skin rash in addition to flu-like symptoms.

Measles often causes a skin rash in addition to flu-like symptoms. Tech, Science, & Innovation

Tech, Science, & Innovation