What is it like to experience homelessness? What do people see when they're living on the street?

Those are the questions that Jason Williamson, an amateur photographer (who also happens to be a pastor at Anderson Mill Road Baptist Church in Spartanburg, South Carolina) found himself asking one day.

Williamson's church spends a lot of time working to combat homelessness in the local community. And after hearing about a recent homelessness photography expo at London's Cafe Art, Williamson realized the idea was just what his community needed to take bigger steps forward.

"[It was] a perfect way to combine photography, a passion I've had for a long time, with outreach in the community," he said.

“This man is homeless. He didn’t want his face in the picture. He was just hangin’ out because that’s what homeless people do. They hang out and wait for food or for a place to open. They wait for something to happen.” — "Hangin' Out" by Ray Kelly. All images used with permission.

Williamson passed out 100 disposable cameras to homeless folks around his city, hoping to "give them a voice where normally they wouldn't have one."

As part of the Through Our Eyes project, ministry volunteers went to shelters, libraries, and soup kitchens to recruit a variety of homeless individuals, ranging in age from 7 to 75. Each person was handed a camera and told to take photos of whatever they wanted — where they hung out, where they stayed, what they ate, who their friends were — and then to return them to a designated shelter five days later.

"I've been doing photography as a hobby for over 18 years, and I knew the satisfaction that I got when I created something. I wanted these people who are on the streets to feel something different, to be inspired and feel that joy," Williamson explained.

As an added incentive, the shelter threw a little party for everyone who came back with a camera on that last day and provided each of them with a meal, a hygiene kit, and a nice new T-shirt with the word "Photographer" emblazoned in big block letters across the back.

“I took it for the simple fact that if he saw his own picture, he’d have to stay out of trouble.” — "Trouble Free" by Donald Edwards.

46 cameras got returned on Day 5, and folks took more than 700 pictures.

Some of the photos were stunning and, yes, some of them weren't so great. But it was the content of the photos that really stood out.

Sure, there were plenty of photos of overpasses, trash, and the burnt-out husks of buildings where groups have gathered for shelter.

“Someone set this place on fire because they got jealous that someone else stayed in there.” — "Hatred" by Ray Kelly.

But more importantly, Williamson and his ministry were overwhelmed by the hope and optimism they saw in some of the pictures.

“He’s my friend and he will talk to anyone and help anyone out. I asked him if he would help me with the project and he wanted to help other people see what’s going on too.” — "Cool Cat" by Donald Edwards.

There were shots of fathers with their daughters...

“She’s my world. She’s everything. And she’s how I got through a dismal situation. She kept me going when I didn’t necessarily think I should.” — "The Light of my Daughter" by David Minch.

...of friends posed together with peace signs and love…

“We had a prayer time out back at the mission one night and I came up with the idea for the photo. We are all family here. I don’t see colors or nationalities; we are all equal. And the love. The love is good.” — "The Love is Good" by Annette Barnett.

...of things that the photographers themselves loved, ranging from the beautiful to the mundane…

“I love that white dress. It reminded me of when my sister got married.” — "Beautiful Dresses" by Bobbie Nesbitt.

...of murals and church signs that inspired them on their daily treks…

“I go to the Journey church every Sunday. I get what I need there. I love Pastor Chris and he really loves the people. The Journey feeds me spiritually and I always feel so good after I leave. Chris always has exactly the message I need to hear each week.” — "Journey" by Leslie Broome.

...and there were even carefully set up still life portraits of meaningful personal possessions.

"I was trying to take pictures of things I see on a daily basis and I really value him. It was a gift. Prayer is a big part of my life. He has a button that says, ‘now I lay me down to sleep,’ when you push it. I know my prayers are being answered. Anything outside of God’s will isn’t going to work anyway.” — "Prayer Bear" by Leslie Broome.

In short, the photos humanized the epidemic of homelessness in a way we don't often see.

“My friend was having a problem and was on the phone, I just happened to catch it. We’re here at the shelter, but it ain’t the end. We’re just going through it. We’ve got a purpose, you just have to go for it and it will come for you.” — "The Struggle" by Allen Johnson.

All 700 of the photographs were then featured in an art show at the Chapman Cultural Center, which also served as a fundraiser for the ministries working to fight homelessness in the area.

Visitors to the exhibit could "vote" on their favorites by putting coins or bills into the "spare change" lockboxes that accompanied each picture. Williamson and a team of judges selected the "Top 20" photographs to sell off at a live auction, with the proceeds split between five different charitable groups for homelessness.

"It gave [these individuals] an opportunity to be a part of the solution [to homelessness], instead of just the problem that other people are trying to fix."

“I knew her from another shelter. I was going to help her get her clothes out and thought I’d take her picture first. I was excited to have a friend here, but I felt bad because she didn’t have a choice but to come to the shelter.” — "Moving In" by Mildred Johnson.

And the photographers whose work fetched the highest bids in the auction? They each received a personalized prize package to help them get back on their feet.

Each package was unique to the winner, providing them with goods and/or services to help them on their own unique journeys.

If nothing else, the other photographers got to enjoy a meal and the brief sense of elation and fame that comes with having people pay attention to something you created. "They told us that, for a moment in time, it made them feel important," Williamson said. "They had a voice and could tell their story in a way they never could before."

“He was sitting under a tree in the shade and I saw the light coming in from behind him. He was in a good posture. The pictures says that you can just relax and be free.” — "Doug" by Rumchanh Park.

While Through Our Eyes didn't bring a sudden end to homelessness in Spartanburg, it did have a powerful impact on the lives of a few fortunate people.

Williamson shared one story of a Through Our Eyes participant who just began working full-time for one of the parishioners at The Mill. This man still lives in a shelter for the time being, but this turn is a positive step forward in his life.

There was also a woman who was so moved by the ministry's embrace of her photography work that she sought out her baptism and became a Christian.

Another boy reconnected with his grandmother Nevada, after she heard about the project on the news. He's still homeless for now, but a local ministry was able to find him and deliver a care package from his grandma.

Of course, even these inspiring stories only account for a fraction of the people in the Through Our Eyes project, and not every story was as successful. But for these individuals, it made a tangible difference.

"Every day, more people are coming into homelessness and out of homelessness than I would have expected," Williamson said. "But I think the cross-section we have here has done a lot to help people in our community understand, and in providing real things."

“This represented the pain and the bad decisions I used to make in the past. This photo means a lot because it reminds me that if I get in a good place, I want to help people. I never cared about if someone saw me laying there, there were no rules. I respect myself a lot more now. There’s help out there, you just have to go to it.” — "Pain" by Allen Johnson.

Through Our Eyes made homelessness visible to the people of Spartanburg in an inspiring new way.

And more importantly, it made those people who live on the street feel like people again, even if it was just for a little while.

As Williamson said, "The cameras that we used were disposable. But the people behind them were not."

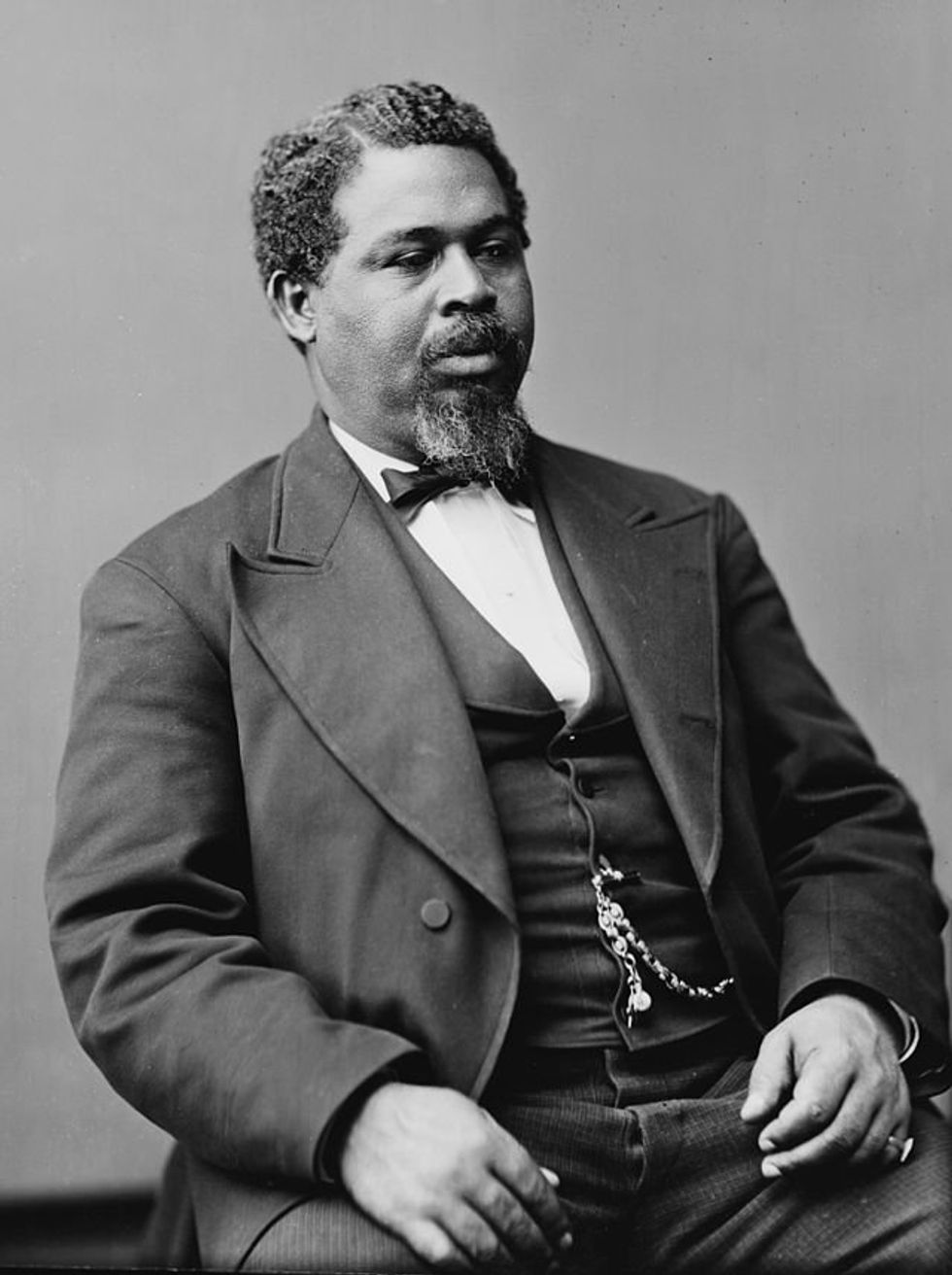

Robert Smalls, S.C. M.C. Born in Beaufort, SC, April 1839Library of Congress

Robert Smalls, S.C. M.C. Born in Beaufort, SC, April 1839Library of Congress Robert Smalls' house in Beaufort, South CarolinaPublic Domain

Robert Smalls' house in Beaufort, South CarolinaPublic Domain