Debunking doesn't stop misinformation online. But researchers found 'pre-bunking' can.

This approach is more effective than fact-checking.

Some helpful information to fight misinformation.

The rise of misinformation on social media has been a monumental stress test for the world’s critical thinking skills. Misinformation has had a huge influence on elections, public health and the treatment of immigrants and refugees across the world. Social media platforms have tried to combat false claims over the years by employing fact-checkers, but they haven’t been terribly effective because those who are most susceptible to misinformation don’t trust fact-checkers.

“The word fact-checking itself has become politicized,” Cambridge University professor Jon Roozenbeek said, according to the Associated Press. Further, studies show that when people have incorrect beliefs challenged by facts, it makes them cling to their false assumptions even harder. These platforms have also attempted to remove posts containing misinformation that violates their terms of service, but this form of content moderation is often seen as insufficient and is often applied inconsistently.

How do we combat dangerous misinformation online if removing false claims or debunking them hasn’t been effective enough? A 2022 study published in the journal Science Advances by a team of university researchers and Jigsaw, a division of Google, found a relatively simple solution to the problem they call “pre-bunking.”

Pre-bunking is an easy way of inoculating people against misinformation by teaching them some basic critical thinking skills. The strategy is based on inoculation theory, a communication theory that suggests one can build resistance to persuasion by exposing people to arguments against their beliefs beforehand.

The researchers learned that pre-bunking was effective after conducting a study on nearly 30,000 participants on YouTube.

“Across seven high-powered preregistered studies including a field experiment on YouTube, with a total of nearly 30,000 participants, we find that watching short inoculation videos improves people’s ability to identify manipulation techniques commonly used in online misinformation, both in a laboratory setting and in a real-world environment where exposure to misinformation is common,” the recently published findings note.

The researchers uploaded videos into YouTube ad slots that discussed different types of manipulative communication used to spread false information such as ad hominem attacks, false dichotomies, scapegoating and incoherence.

Here’s an example of a video about false dichotomies.

- YouTubeyoutu.be

Researchers found that after people watched the short videos, they were significantly better at distinguishing false information than they were before. The study was so successful that Jigsaw is looking to create a video about scapegoating and running it in Poland, the Czech Republic and Slovakia. These countries are all combating a significant amount of false information about Ukrainian refugees.

Many people talk about "critical thinking," but a lot of people don't really understand what the term means. Learning about the tropes and techniques used to spread misinformation is a vital part of developing critical thinking skills. It's not just about thinking for yourself and determining what's true based on what your brain tells you; it's about recognizing when messaging is being used to manipulate your brain to tell you certain things. It's learning about logical fallacies and how they work. It's acknowledging that we all have biases that can be preyed upon and learning how propaganda techniques are designed to do just that.

There’s an old saying, “If you give a man a fish, he’ll eat for a day. Teach that man to fish and he’ll eat forever.” Pre-bunking does something very similar. We can either play a game of whack-a-mole where social media platforms have to suss out misinformation on a minute-by-minute basis or we can improve the general public’s ability to distinguish misinformation and avoid it themselves.

Further, teaching people to make their own correct decisions about misinformation will be a lot more effective than pulling down content and employing fact-checks. These tactics only drive vulnerable, incredulous people toward misinformation.

This article originally appeared three years ago.

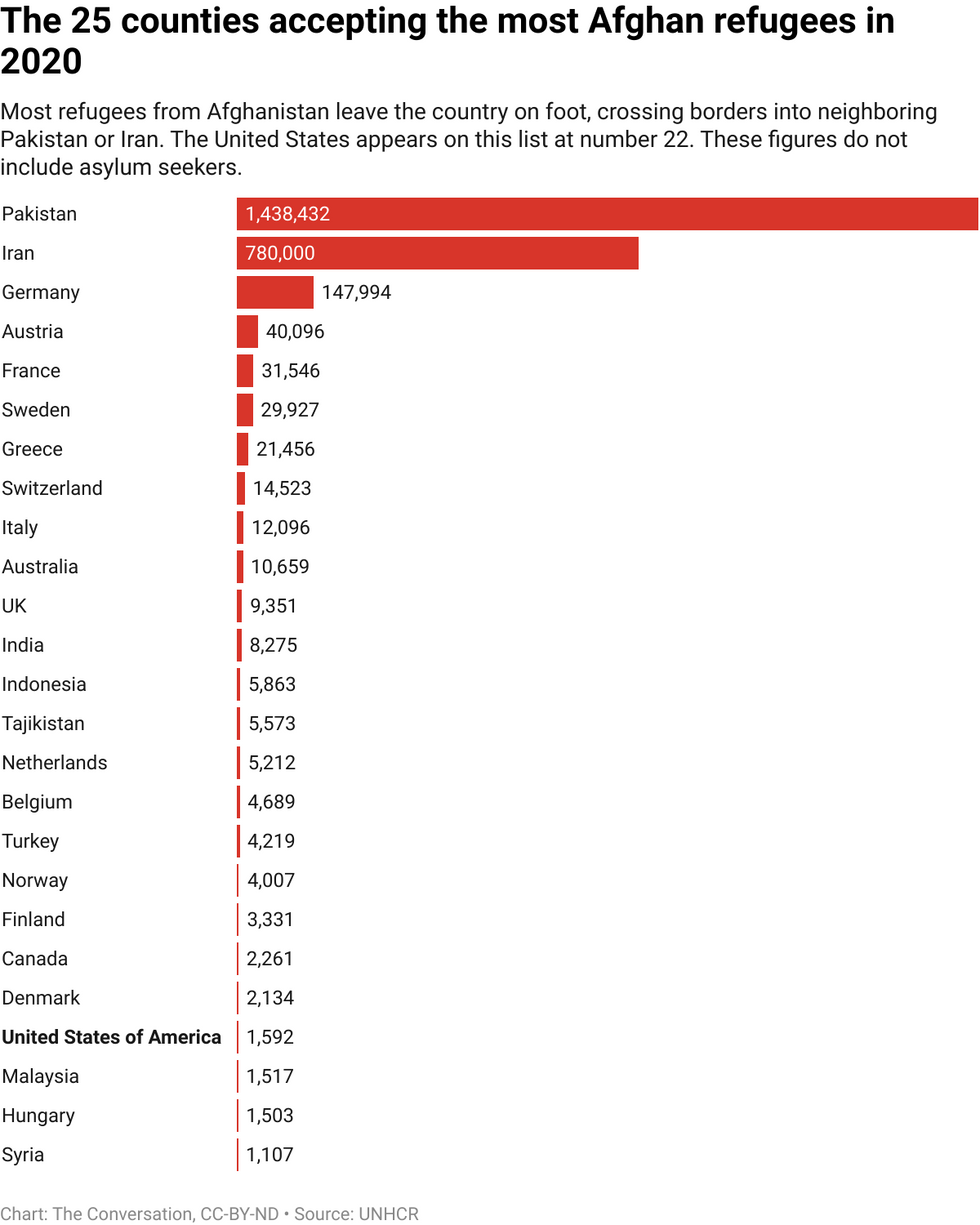

Chart: The Conversation, CC-BY-ND Source:

Chart: The Conversation, CC-BY-ND Source:  Afghan refugees enter into Pakistan through a border crossing point in Chaman while a Pakistani army soldier stands guard.

Afghan refugees enter into Pakistan through a border crossing point in Chaman while a Pakistani army soldier stands guard. Despite the presence of the Taliban, a group of protesters march with Afghan flags during the country's Independence Day rally in Kabul, Afghanistan on Aug. 19, 2021

Despite the presence of the Taliban, a group of protesters march with Afghan flags during the country's Independence Day rally in Kabul, Afghanistan on Aug. 19, 2021