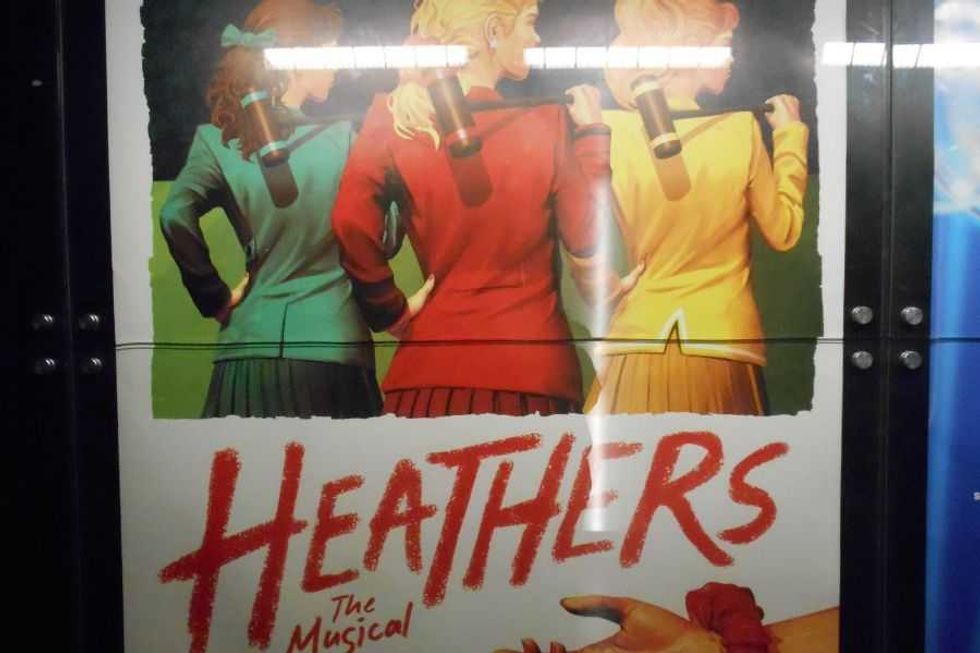

Two Gen Zers told me 'Heathers' was inappropriate for teens. Here was my Xennial response.

I was so confused when they said no high school should be putting on the musical.

I was shocked when two Gen Zers said 'Heathers' is inappropriate for teens

It's true, not every Gen X movie is suitable for teenagers. But does that really ring true for movies that were quite literally made for teens? According to two Gen Zers, yes. Their argument over the musical, Heathers, being performed by high school students perplexed me because I watched the movie when I was around the age of eight or nine.

Now, it has been years since I've seen the movie, so I figured that I must be misremembering it. But I also know that I once considered it tame enough for my own child to watch it in middle school—eighth grade to be exact. It's still one of her favorite movies at the age of 25, and the only reason I was aware there was a musical based on the 1988 cult classic.

Very rarely am I around young adults or older teens (who are not my own children or their friends), where topics like these might come up. But currently, I'm in the production of a community play where people of all ages are cast, so I've gotten to know quite a few younger and older people. Two girls, 17 and 20, were chatting with me about different subjects when the topic of favorite Broadway shows came up. Heathers was at the top of the list for the younger one, but she expressed her dismay when she revealed that one of her friends performed in the show at her high school.

This raised my curiosity. I had never seen the musical, so I decided to inquire about the reaction both girls had to a high school performing a musical about high school girls. Immediately, they deemed high schoolers putting on a production of Heathers to be inappropriate. That made me even more curious, so I asked about their thoughts on the movie and informed them that I watched it as an elementary-aged child. The Gen Zers explained that neither the movie nor the musical is appropriate due to the themes of drug use, promiscuity, and suicide.

Curiouser and curiouser, I thought, because sex, drugs, and suicide were all things that high schoolers have been dealing with for decades. It hardly seems inappropriate for teenagers to view a movie or musical with teens experiencing those themes, but according to the girls, "It was a different time" when I grew up. Indeed, it was a different time, and I was a cusper, which put me on the edge of two generations within my own household and society. The only reason I was watching Heathers at such a young age is that I had a Gen X brother in the house with parents still adjusting their parenting style in accordance with the changing times.

But when I asked my own daughter about the appropriateness of the movie and musical for teenagers, her answer shocked me as well. She explained to me via text that she, too, didn't think high schoolers should be performing the play, saying, "The movie is fine the play is not. There's a full sex scene with a song." But that was where her agreement ended.

In all fairness to high school drama teachers everywhere, the sex scene is likely cut for the high school version. Still, the initial concern makes me wonder if we were desensitized to themes that should've been treated more seriously, or if we've possibly been too overzealous in protecting our Gen Z children from themes in life they'd inevitably have to navigate?

Teenagers have essentially been the same since the first human infant made it to adolescence. Sure, technology, slang, and other things have changed, but child brain development is consistent. Teens are going to push boundaries. They're going to experiment with things they've been told to avoid. Teenagers are going to lack impulse control and participate in risk-taking behaviors, whether it's 2078 or 1802; it's part of normal human brain development.

So, it's surprising that these Gen Z kids feel like themes that occur in real-life high schools across the country are inappropriate for real-life teenagers to watch in a movie. This may be specific to these two young girls, but it does seem that Gen Z in general has a much different reaction to '80s teen angst movies than older generations. Maybe it's due to having more understanding of how toxic certain behaviors were that were once normalized, or something more inherent to this generation. Either way, getting to know how the younger generations interpret things can be quite fascinating, and I always feel privileged when their thoughts are shared with me.

- Gen Z grew up in a screen-saturated world. They're vowing to raise their kids differently. ›

- I convinced my Gen Z kids to watch 'Dead Poets Society' and their angry reactions surprised me ›

- My Gen Z kids say periods in my texts are 'aggressive.' I'm not stopping anytime soon. ›

- 27 life-changing movies old people want young people to see - Upworthy ›