5-year-old saves his family from devastating house fire after receiving a 'message from God'

"God’s protection was over him the whole way."

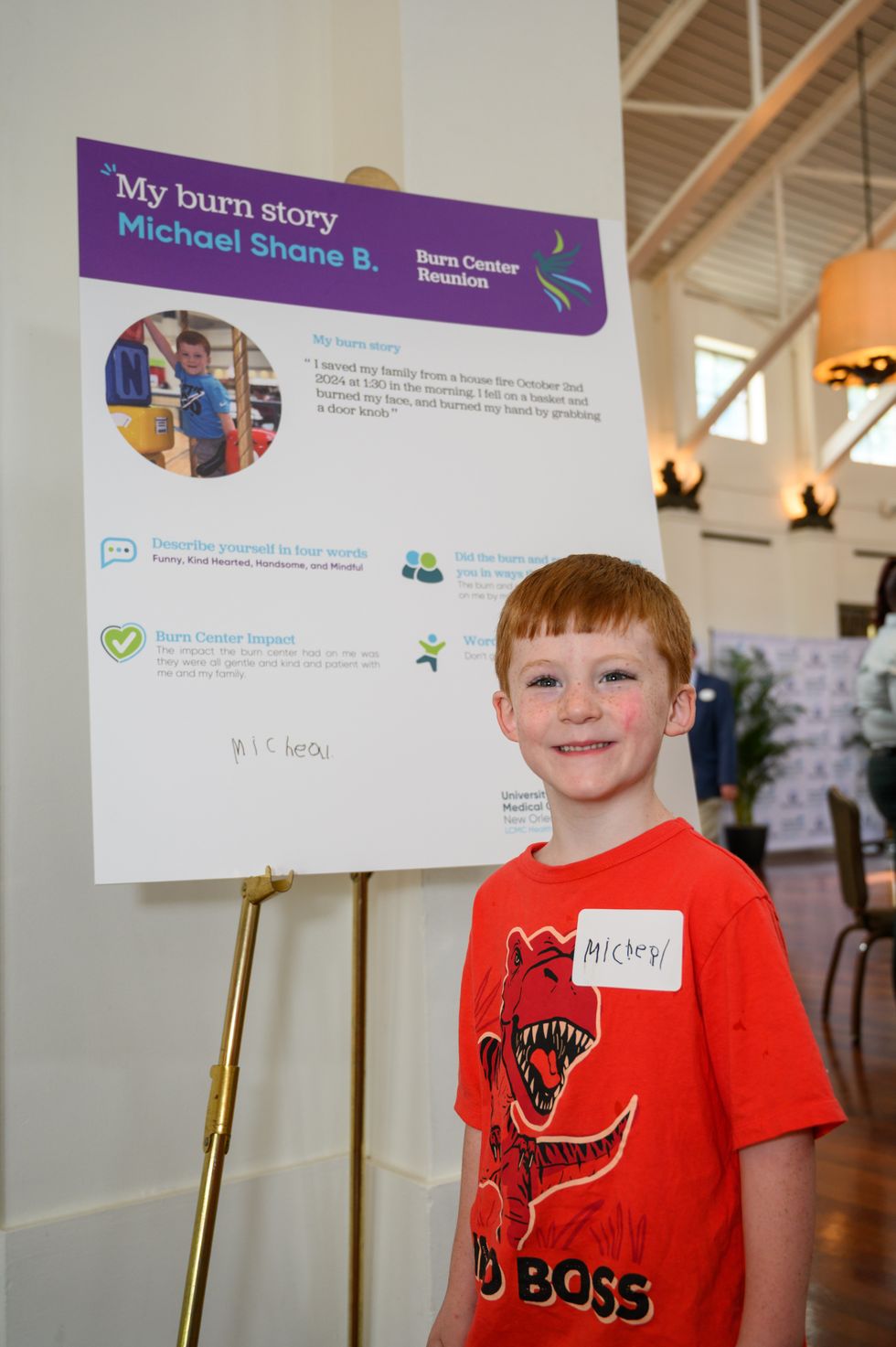

Michael Butler saved his family from a fatal house fire in October 2024.

Five-year-old Michael Butler is a hero. Early in the morning on October 2, 2024, the family’s trailer in rural Jonesville, Louisiana, had caught on fire, quickly engulfing it in flames. Michael woke from a deep sleep after hearing a message from God.

“Michael told us he received a message from God that said he needed to go wake his mama and daddy up,” Chaya Butler, Michael’s mother tells Upworthy. His dad, Trenten, adds, “We were woken up by him screaming.”

Michael had run from the far end of the trailer through fire to reach his parents bedroom, suffering burns on his back from melting nails in the roof and to his face after falling into a melted plastic laundry basket on his parent’s bedroom floor. The hand he used to open the bedroom door was scalded, but none of it stopped him.

“After he woke us up, we struggled to get out of the bedroom. We couldn’t see anything because the smoke was so thick and we went to the wrong door 3 times thinking it was our bedroom door [and way out],” Chaya says.

“It was terrifying. The only thing on my mind was getting my family out,” says Trenten.

Chaya and Trenten were able to get Michael's little sister out of the home, as well as two other family members who were staying with them. However, two other family members did not survive, as well as four family pets.

The devastating night could have resulted in an even more catastrophic outcome and the family credits Michael’s faith with saving their lives. “We had been going to church every Sunday. Never missed a service,” says Trenten. “We had gotten baptized, and we were heavy with the Holy Ghost. Michael was praising the Lord, praying and going to the altar. He would pray before eating and going to bed.”

Michael escaped with severe burns that required him to undergo four different surgeries, including skin grafts, at The Manning Family Children's Burn Center in New Orleans. (His family also suffered burns that have left scars.) However, Michael’s feet were spared–something his family calls miraculous.

“Michael was barefoot. There is no way he walked through the house without burns on his feet without God. God’s protection was over him the whole way,” says Trenten.

During his recovery, Michael continued to persevere. “He had a cast on for a while, but he was resilient; he didn't let it slow him down or stop him,” adds Trenten.

The family has slowly been rebuilding their life and coping with lasting nightmares from October 2, 2024. (The family has started GoFundMe.)

“It has definitely been a journey. There are a lot of questions that haven’t been answered. Why us?” says Trenten. “God gives his toughest battles to His strongest warriors. We will never be back to ‘normal’ but we are making our own normal. We’re slowly getting there. Rock bottom isn't always the bottom–you can always come back up. We definitely hit that. But having your life is just as beautiful. ”

However, they hope others will be inspired by their story and their son Michael’s strong spiritual connection.

“Even if you have faith the size of a mustard seed, God is always with you,” says Chaya.

- Heart-stopping video shows the moment a hero dad saves neighbor's child from drowning ›

- Meet the 15-year-old hero who just gave the U.N. some real talk about the future of his generation. ›

- Denver 3-year-old bravely saves great-grandma after she fell outside while babysitting him ›

- Utah teens break down neighbor's door to rescue dogs from house fire - Upworthy ›

- Man taking afternoon nap hears odd 'popping' noises—minutes later, a stranger pulls him to safety - Upworthy ›