Researchers hacked 5 people's brains so they could see a new and impossible color

The new color 'olo' is neat, but the technique behind it could be groundbreaking.

Only five people in the world have seen the mysterious color "Olo"

Color is one of the great joys of being alive. The brilliant blue sky, the green grass, the exotic pinks and purples and teals in coral or tropical fish. Soaking it all in is truly a feast for the eyes, and some studies even show that certain colors can trigger specific emotions in people. Orange may evoke feelings of joy, and red may conjure feelings of love, while blue may have a calming effect.

One of the most interesting things about colors, though, is that they are finite. Though the world is full of undiscovered plants, creatures, and even elements, the entire color spectrum is known and documented. Due to the nature of light in our universe and how it reflects off of physical objects, all perceived color must be created by some combination of the primary colors (blue, green, and red — yes, green, not yellow!). There are essentially unlimited combinations, but they all exist on a known spectrum — different hues and shades of pink or emerald or orange.

However, a team of researchers recently decided to push the limits of human perception. They "hacked" participants' retinas to allow them to see an impossible color.

Scientists from the University of California, Berkeley, developed a new technique called "Oz," which would allow them to activate specific cones in the retina. Cones are light-sensitive cells that respond to different wavelengths of light. When the three types of cones are activated in different ways, our brains perceive colors.

One fascinating bit of background is that the "M" cone, which typically responds strongest to green (Medium wavelength), can not naturally be activated without also activating the Long and Short cones. So even the purest green on the planet would also, to a smaller degree, stimulate the parts of our eyes that are mostly correlated with red and blue.

The team wanted to find out what would happen if they could isolate and activate only the M, or green, cone using the new technique.

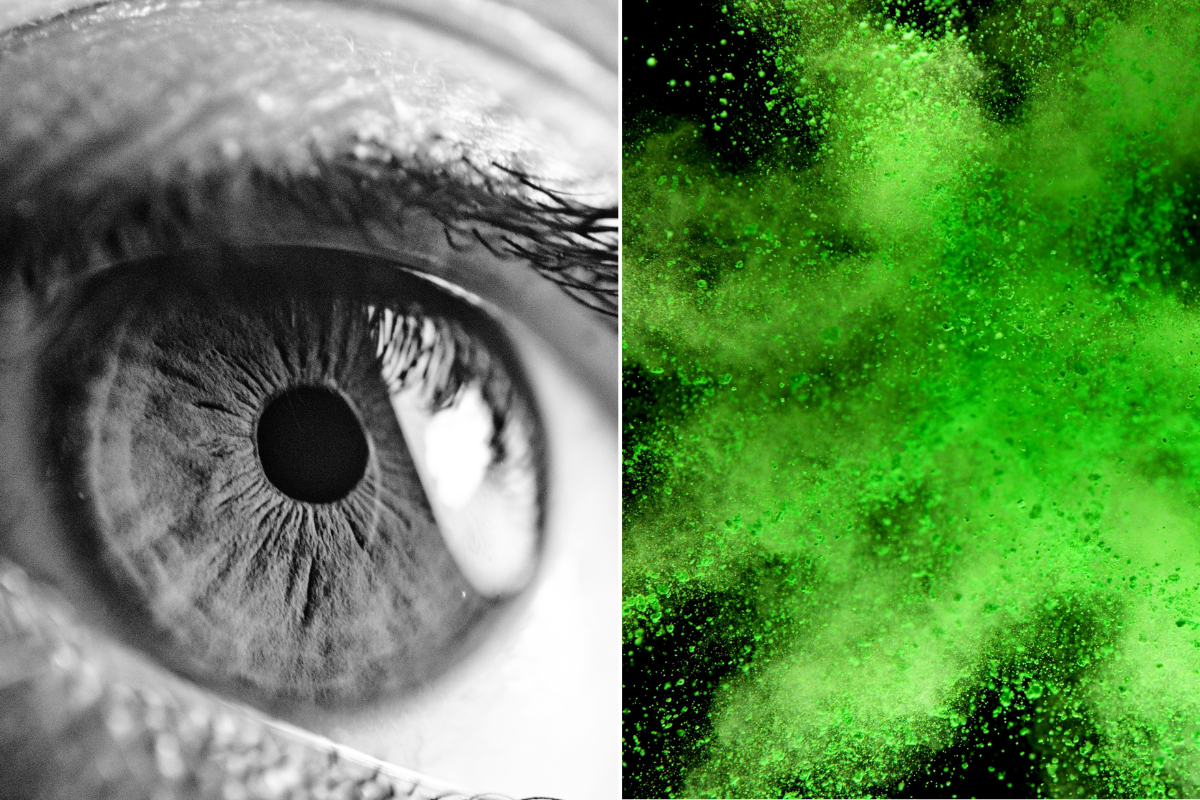

The result? The five participants reported seeing an absolutely unreal, brilliant shade of green like nothing they had ever experienced. Imagine a bright green laser cranked up to the highest saturation and brilliance possible, the purest and brightest green your brain could possibly comprehend. Participants noted that a bright green laser pointed looked "pale" in comparison to the new color.

The name of the new, impossible color? Olo, or 010 (indicated zero stimulation of the L and S cones and full stimulation of the M cones).

- YouTubewww.youtube.com

It's fair to wonder, if olo is impossible and can never naturally exist without manual stimulation of the retinal cones, what's the point of the experiment?

The introduction of a "new color" is certainly interesting and makes for a good headline, but the real value of this study lies in the future applications of the Oz technique.

The research team hopes that the detailed retinal maps they have developed, along with their ability to stimulate specific rods and cones in the eye in any combination, will enable major breakthroughs in the study and treatment of various visual impairments.

For example, Oz could one day cure color blindness or unlock new treatments for cataracts or glaucoma. It could even play a role down the line in curing certain types of blindness. Isn't it wild how our understanding of how our eyes perceive color tells us so much?

But those days are a long way off, for now. In the meantime, only five people in the world have experienced the brilliance of olo, and the rest of us will just have to imagine it.

- Bob Ross once shared the joy of painting to a colorblind viewer using only black and white ›

- Red, yellow and blue aren't actually primary colors, according to updated color wheel ›

- Recently discovered sketches underneath a Leonardo da Vinci painting give us insight into his process ›

- People are rebelling against Pantone's 2026 'Color of the Year' by choosing their own color instead - Upworthy ›