William isn't allowed to tell his LGBTQ students he's on their side, so he has to do it in code. When he overhears them chatting with friends, he strains to absorb the language they use with one another and repeat it one-on-one. In counseling sessions, he refers to the significant others of students and school staff as their "partners" instead of "boyfriends" or "girlfriends."

He had second thoughts about hanging a sign in his office that reads: "Your identity is not an issue."

"I actually checked with my bosses ahead of time," he says. "They were like, 'Nope, you’re good!'"

As a middle-school psychologist in Virginia, William (who requested his real name not be used, for fear of retaliation) has always had to skirt around school board rules restricting his ability to address the fears and challenges of his lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, and queer students out loud. But things have changed.

Before January, William says he would hear a homophobic or transphobic slur from a colleague (not all bullies are students, it turns out) maybe once a month. Now, he says, those voices have gotten much louder — and more persistent.

"The sad part is I can't be as loud as they can be without getting in trouble," he says.

For many school psychologists, sticking up for their LGBTQ students in the Trump era feels a lot like paddling over a cultural tidal wave.

Their efforts are frequently complicated by having to navigate a patchwork of guidelines and legislation governing what they can and can't say, and what they must reveal to parents if asked. Eight states restrict how teachers discuss some LGBTQ topics in schools.

That leaves some educators worried they're not doing enough.

"I’m seeing school counselors who were maybe feeling like they were sitting pretty with their programs and what they had been offering their LGBTQ youth at their sites now ramping it up," says Catherine Griffith, assistant professor of student development at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst School of Education. That means asking for more trainings and workshops, particularly on how to talk about trans-specific issues, like pronoun usage and bathroom conflicts.

A student in Massachusetts works on homework. Photo by Jewel Samad/Getty Images.

Griffith recommends approaching conversations with struggling students by listening first and recognizing their expertise on their own lives. She also endorses approaches like William's, in which counselors use visual cues (like a sign hanging in an office) and specific language to signal support. Her research into interventions for LGBTQ youth led to the development of a curriculum — which she distributes free to educators — that emphasizes the helpfulness of organized groups to combat social isolation.

For students, Griffith explains, the ability to organize helps them learn from peers, develop a sense of altruism, and bear witness to others' challenges, especially when it feels like voices in positions of authority are aligned against them.

While William struggles to sneak a kind word to a struggling eighth-grader, 3,000 miles away, the kids in Cynthia Olaya's Campus Pride Club are lighting bonfires on the beach.

A 14-year veteran psychologist from Long Beach, California, Olaya looks younger than her 40 years, a stroke of genetic good fortune that she believes makes it easier for students to open up to her.

"I don’t know how much longer I’m going to be able to use that," she jokes.

Here in Fountain Valley, where she helps oversee the two-decade-old group, the Trump administration feels far away — literally and figuratively. Earlier this year, when rumors began swirling that the president was prepared to sign an executive order allowing business owners who cite religious convictions to discriminate against LGBTQ customers, her principal addressed the controversy, bluntly, over the school loudspeaker.

"He said, 'Don’t worry students. We’ve still got your back,'" Olaya recalls.

The club, formerly a Gay-Straight Alliance, recently rebranded to be "more trans-inclusive." Her LGBTQ students benefit, she explains, not only from the group, but from robust institutional support and, perhaps most critically, support from their elected representatives. Last year, the state board of education approved a measure requiring that schools add the contributions of LGBTQ Americans to history lessons as early as second grade. A 2017 law bans state-funded travel to states that have anti-LGBTQ laws on the books. In California, there are no rules preventing her from freely discussing her students' gender and sexual orientation.

Her students are worried about what the Trump administration might do to rollback their rights, but most are not panicking — yet.

"I think they feel like, 'We’re safe here,'" she says.

The Trump administration has alternated between playing coy with LGBTQ rights and launching an all-out assault on the policies of the Obama administration.

Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images.

At times, both approaches appear to be on the table simultaneously. The draconian religious freedom order Olaya's students feared in February turned out to be little more than a symbolic statement when it was signed in May. The president announced a similarly harsh measure to ban transgender Americans from serving in the military — but has yet to take steps to implement it. The military, it appears, is ignoring it for the time being.

How LGBTQ kids fare in this whipsaw environment can have less to do with how much their counselors want to help and more with the institutional and legal frameworks that govern how much they can help.

Some communities have followed the president's lead in loosening, or refusing to enforce, current protections. Others are resisting the charge.

In some places — the jury is still out.

Holiday, Florida, is an area in constant transition. In the middle school where psychologist Jacalyn Kay Jackson works, immigrants and students of color mix with white students from "more conservative" families. Many arrive in the district for a year or two before moving on. 80% are on reduced or free lunch. Many are LGBTQ.

Since the inauguration, Jackson says her students have been showing "more anxiety" than usual. While Muslim and immigrant students have received the bulk of harassment from their right-wing peers, the backlash has been stinging her LGBTQ kids as well.

"We did have some transgender students and gender-nonconforming students who were worried that some of the rights that they felt that they had fought hard for were being taken away," she says.

Jackson has held the role of LGBTQ liaison for her district since last school year — and she's thrilled about it. She spends half a day a week teaching other educators in the district how to best support gay, lesbian, bisexual, queer, and trans youth, how to navigate locker and restroom issues, and how to create safe spaces for discussion and recovery from trauma. She's working on a 60-page best practices guide, which she plans to distribute to teachers in her district this coming school year. Despite the occasional complaint, her district is fully behind her work — which gives her much-needed cover.

In her area of Florida, the 2016 shooting at Orlando's Pulse nightclub opened a lot of eyes to the dangers LGBTQ youth face. She hesitates to call it a "silver lining," but that's the phrase that comes to mind. More parents have been going to Pride parades. Many who were formally opposed to, or equivocating on, expanding LGBTQ rights in the district have come around a bit.

"Not that they’re actively supportive, but maybe they’re more possibly supportive, perhaps because it hit closer to home than it ever has been," Jackson says.

A person builds a balloon rainbow near the site of the Pulse shooting in Orlando. Photo by Spencer Platt/Getty Images.

It's not a cakewalk. Some students in Jackson's school still face rejection from their families. As the Trump administration attempts to dismantle Title IX guidelines and rollback trans-inclusive policies in the military, LGBTQ kids, she explains, need a "buffer to what [they're] hearing on the news," which for many, isn't at home.

Still, with support strong and growing, at school, that "buffer" appears to be holding — for now.

The only reason her work is possible in this social and political climate, she explains, is the last five years of rapid-fire progress toward LGBTQ inclusion and equality.

"Kids really heard a message when marriage equality came through, and prior to that as some of the individual states started recognizing marriage equality," she says. Meanwhile, parents and colleagues who were previously supportive are looking for ways to be more supportive — particularly of trans students.

Photo by Spencer Platt/Getty Images.

"A lot of them were wondering, 'What pronoun do I use?' and 'How do I support them?' and 'How do I have this conversation?'" Olaya says.

Even in areas where it's hard to keep the door open, there are signs that a metaphorical lock has been smashed off. William recalls counseling one student whose relatives were debating sending her cousin to a conversion therapy camp, and she was worried she would be next. Students, especially younger ones, who reveal too much about their sexuality to teachers often run the risk of being outed to their parents, even if the crisis originates at home. This student, like many others, knew she could come to William for help and that he would keep her confidence.

"The kids know how to ask the right kinds of questions," he says.

Increasingly, their school psychologists are trying to find the space to send the right message back.

"The message is: We’re listening, we’re here for you."

A father does his daughter's hair

A father does his daughter's hair A father plays chess with his daughter

A father plays chess with his daughter A dad hula hoops with his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad hula hoops with his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. A dad talks to his daughter while working at his deskAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad talks to his daughter while working at his deskAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. A dad performs a puppet show for his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad performs a puppet show for his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. A dad walks with his daughter on his backAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad walks with his daughter on his backAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. a dad carries a suitcase that his daughter holds onto

a dad carries a suitcase that his daughter holds onto A dad holds his sleeping daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad holds his sleeping daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. A superhero dad looks over his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A superhero dad looks over his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. A dad takes the small corner of the bed with his dauthterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad takes the small corner of the bed with his dauthterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. Yorkie GIF

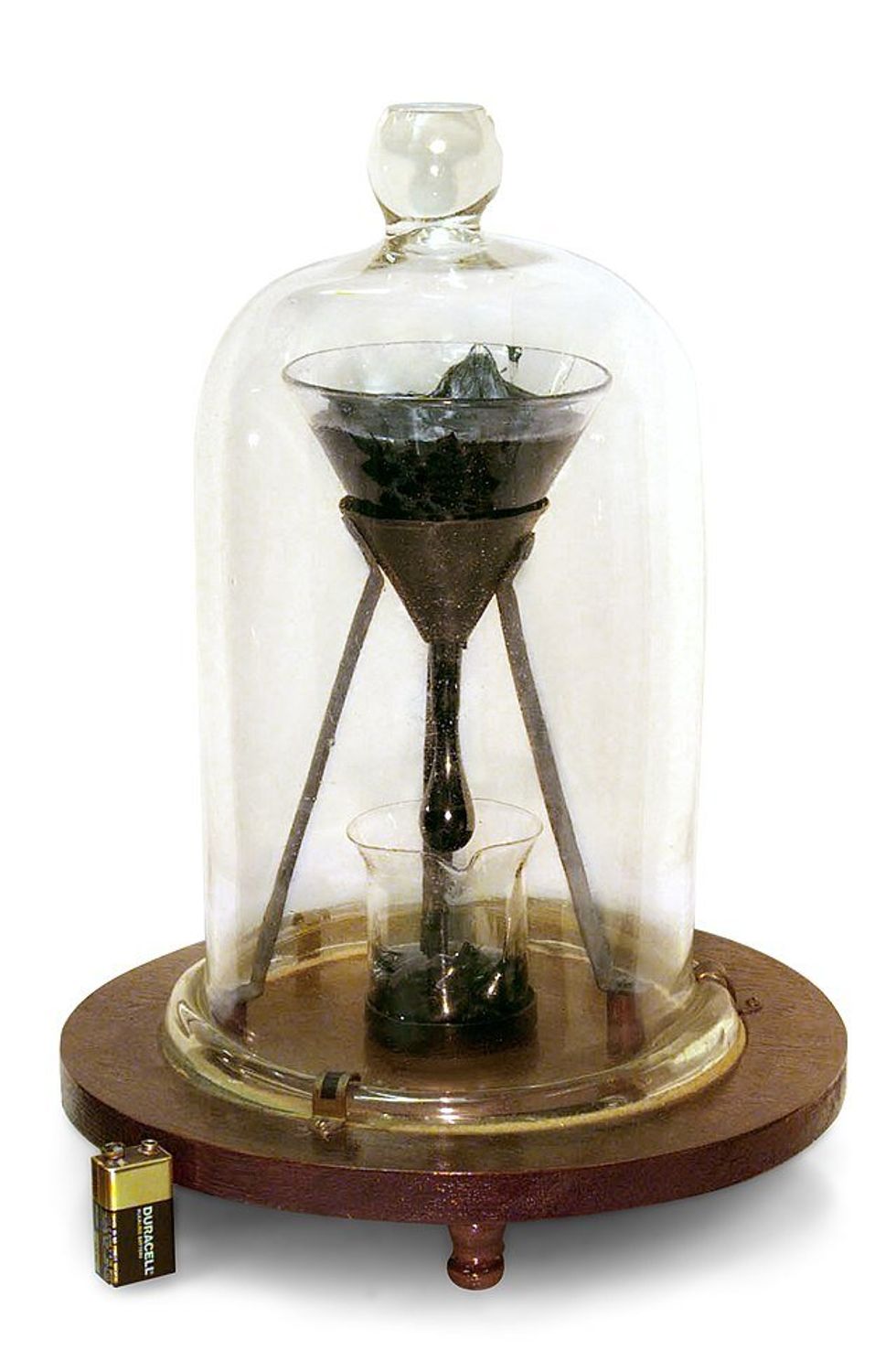

Yorkie GIF Pitch moves so slowly it can't be seen to be moving with the naked eye until it prepares to drop. Battery for size reference.

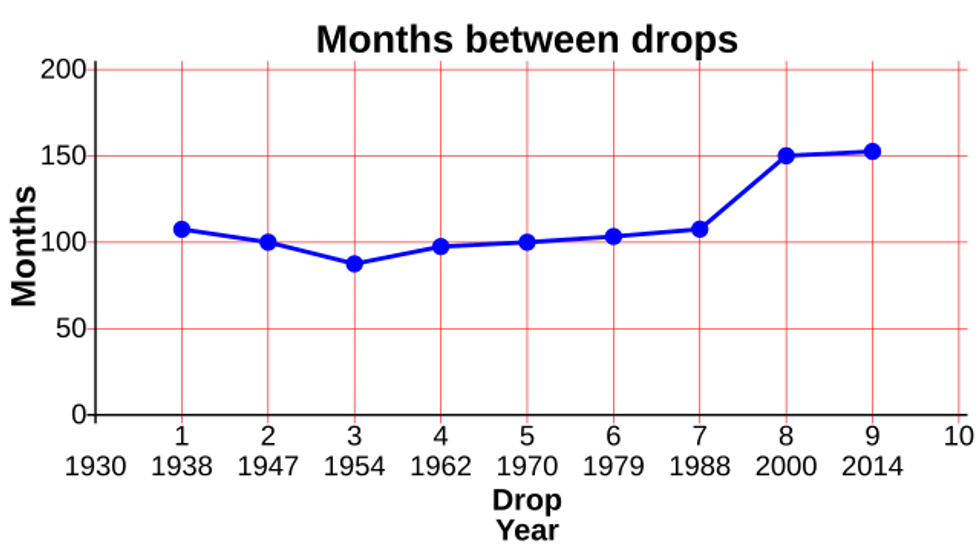

Pitch moves so slowly it can't be seen to be moving with the naked eye until it prepares to drop. Battery for size reference. The first seven drops fell around 8 years apart. Then the building got air conditioning and the intervals changed to around 13 years.

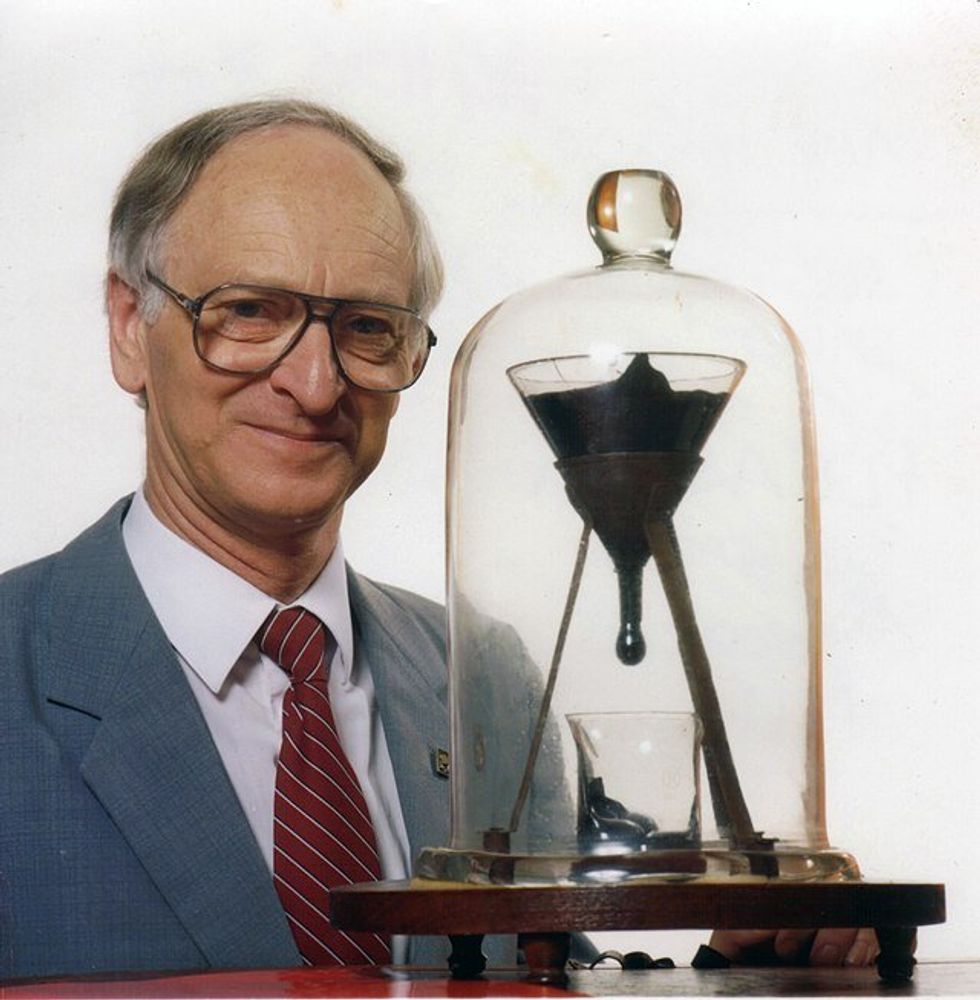

The first seven drops fell around 8 years apart. Then the building got air conditioning and the intervals changed to around 13 years. John Mainstone, the second custodian of the Pitch Drop Experiment, with the funnel in 1990.

John Mainstone, the second custodian of the Pitch Drop Experiment, with the funnel in 1990. shocked cat GIF

shocked cat GIF Bored Cat GIF

Bored Cat GIF