Some people are going bananas about bananas possibly going extinct.

Save the bananas.

You may have heard that bananas are going extinct.

And it's sort of true: The banana as we know it isin danger. But that's also only part of the story.

To understand what’s happening with bananas today, we have to take a look at the bananas of years past ... because we’ve actually been in this situation before.

Years ago, the bananas found in grocery stores didn’t look or taste like the bananas we know now.

They looked like this:

The "original" banana: Gros Michel. Image via iStock.

By all accounts, those bananas apparently tasted better. Known as the Gros Michel strain, they were cloned and mass produced and shipped all around the world until their days as the reigning banana species were brought to an abrupt end. You know that deliciously sweet artificial banana flavoring that tastes nothing like a banana? Well, allegedly, that’s what the Gros Michel tasted like.

So, what happened? Why aren’t we still snacking on deliciously sweet candy-flavored bananas?

The Panama disease, a fungus that destroys any crop that’s susceptible to it, killed most of the supply, bringing the Gros Michel bananas to their knees more than a century ago.

With the Gros Michel banana near extinction, the banana industry went into a panic.

Farmers lost their crops and their livelihoods. The soil was tainted because of the Panama disease, so they couldn’t just start over.

But, luckily, there was a solution: One species of banana proved to be resistant to the Panama disease. It could be planted in the infected soil and would bear fruit — no problem. It was the Cavendish banana to the rescue.

The bananas we're used to seeing! The Cavendish. Image via iStock.

The Cavendish banana is what most of us think of when we think of bananas.

While there are other varieties of bananas sold in local markets, many of which taste sweeter and are fun shades like pink and red, the Cavendish was the best bet for farmers because of its resistance to the disease. It’s not as delicious as the Gros Michel, but it would have to do.

The banana trade made a mistake though: They treated the Cavendish pretty much the same way they did the Gros Michel the century before. Instead of diversifying their banana production, they cloned just the Cavendish and ratcheted up production until the Cavendish became the most dominant banana in the market. Today, about 99% of the bananas consumed worldwide are of the Cavendish variety.

But here’s the thing: Relying too heavily on one species of banana (or any other item, really) can be a mistake.

The red banana. Image via iStock.

That’s called monoculture cropping — growing a genetically similar or identical crop without introducing any variants. And while it bodes well for production because it’s much easier to mass produce genetically identical crop, it also means that the slightest change can put the entire crop at risk. One disease can kill them all.

That’s what happened with the Gros Michel. And it’s on the verge of happening again today with our beloved Cavendish.

The adorably fuzzy pink bananas. Image via iStock.

A new version of the original Panama disease is back with a vengeance, and it’s targeting the Cavendish.

The situation is bad, but it’s not dire — not yet at least. While it feels a bit like a ticking banana time bomb, scientists and banana-breeders are on the case.

They’re trying to mate plants that are resistant to the new disease together, to create offspring that are more likely to make it if this situation repeats itself. They’re creating bananas that are built to survive.

And the farmers and economies that depend on the banana trade? They’re working to diversify their crop and to identify already-resistant banana species that can be grown in soil that’s been compromised by the disease. They’re not just waiting for a solution, they’re creating one.

The adorably tiny Lady Finger bananas. Image via iStock.

Our banana history may be repeating itself, but don't cry yourself to sleep just yet.

This time, we might be ready for it.

We’ve learned that doing the same thing over and over again will probably yield the same results, so we’ve got to change it up. Who knows, maybe in a few years, we’ll find a variety of delicious banana breeds in stores for all of us to enjoy snacking on.

Ronnie Archer-Morgan on an episode of the BBC's Antiques RoadshowImage via Antqiues Roadshow

Ronnie Archer-Morgan on an episode of the BBC's Antiques RoadshowImage via Antqiues Roadshow  Ronnie Archer-Morgan holds the ivory bracelet he refused to valueImage via Antiques Roadshow/BBC

Ronnie Archer-Morgan holds the ivory bracelet he refused to valueImage via Antiques Roadshow/BBC Autumn created this piece when she was just 5 years old.

Autumn de Forest

Autumn created this piece when she was just 5 years old.

Autumn de Forest

Soon, Autumn rose to national fame.Autumn Deforest

Soon, Autumn rose to national fame.Autumn Deforest Autumn de Forest paints

Autumn de Forest

Autumn de Forest paints

Autumn de Forest

An Autumn de Forest painting

Autumn de Forest

An Autumn de Forest painting

Autumn de Forest

An Autumn de Forest painting

Autumn de Forest

An Autumn de Forest painting

Autumn de Forest

Autumn de Forest stands with the Pope who looks at one of her paintings

Autumn de Forest

Autumn de Forest stands with the Pope who looks at one of her paintings

Autumn de Forest

Autumn de Forest works with other young painters

Autumn de Forest

Autumn de Forest works with other young painters

Autumn de Forest

A Nazi book burning in GermanyImage via Wikicommons

A Nazi book burning in GermanyImage via Wikicommons lord of the rings hobbits GIF

lord of the rings hobbits GIF Bryan Cranston Mic Drop GIF

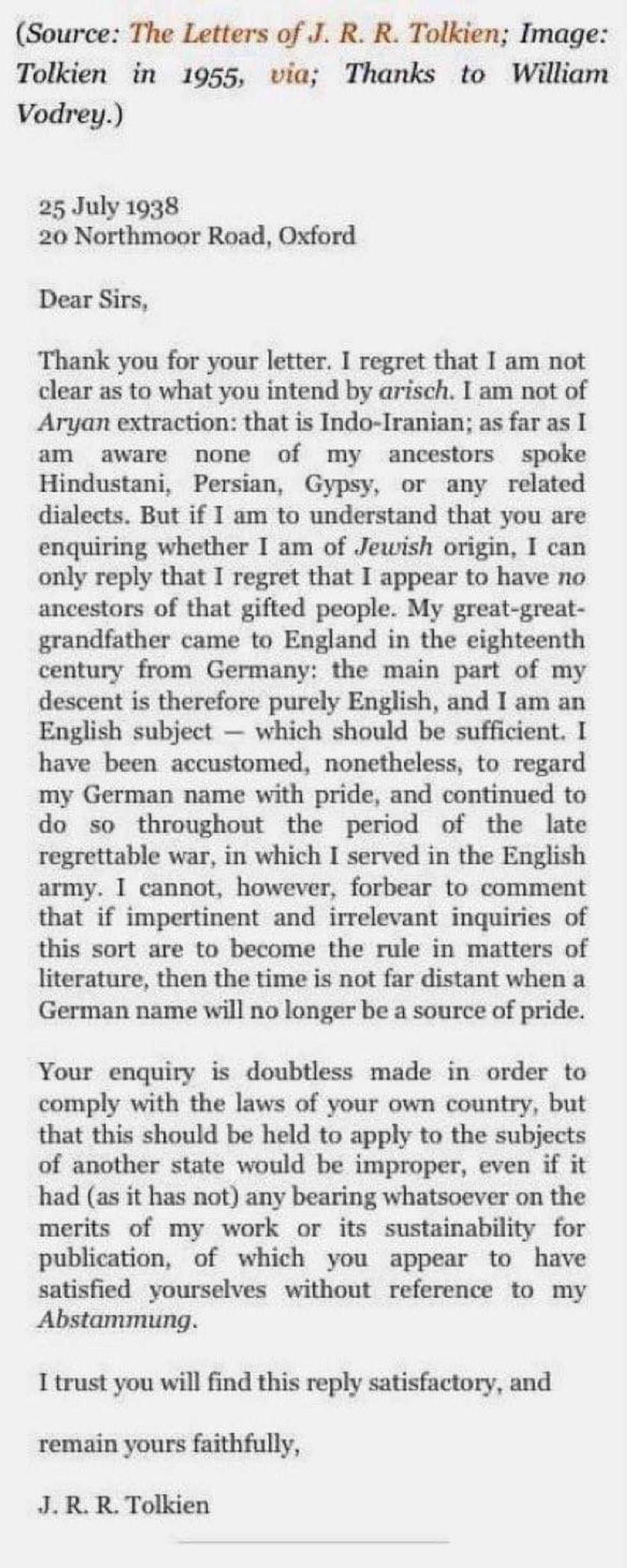

Bryan Cranston Mic Drop GIF The letter J.R.R. Tolkien wrote to his German publishersImage via Letters of Note

The letter J.R.R. Tolkien wrote to his German publishersImage via Letters of Note A group gathers around a birthday cakeImage via Canva

A group gathers around a birthday cakeImage via Canva A person holds an affirmation cardImage via Canva

A person holds an affirmation cardImage via Canva