In the wake of suicide, we're often left with two questions: "Why?" and "How could this have been prevented?"

Neither have easy answers. The painful truth — as evidenced by the recent deaths of beloved public figures Kate Spade and Anthony Bourdain — is that suicide is much more prevalent than many are comfortable talking about. According to statistics, suicide is the 10th leading cause of death in America, claiming more than 44,000 lives each year. More worryingly, a recent report from the Centers for Disease Control shows that suicide rates are on the rise — up 30% from 1999.

What's even more difficult to come to grips with is the fact that suicide isn't a monolith. We may have been taught to look for warning signs in friends and family during our high school health classes and college orientations, but warning signs are often not obvious. Nor, as the tragic deaths of Spade and Bourdain have made distressingly clear, are fame, fortune, and a life that is perceived as "good" inoculations against suicidal thoughts or actions.

If there's anything the conversation that's stemmed from these high-profile deaths has re-affirmed, it's that "suicide doesn't have a look." And while it disproportionately affects some groups — LGBTQ youth, for instance, are more at risk than their non-LGBTQ counterparts — the reality is that anyone can experience suicidal ideation.

Here's the reality: Suicide is incredibly difficult to predict. There are many reasons for that.

In a piece for Big Think, Joseph Franklin, professor of psychology at Florida State University, writes that humans love explanations that are simple and universal. Though this way of thinking is often helpful, it doesn't translate when it comes to the topic of whether someone will commit suicide. In fact, Franklin's research on the topic showed that even when taking risk factors into account, the most trained experts are no better at predicting actual suicidality than "someone with no knowledge of the patient who predicted based on a coin flip."

It would be easiest if there were incontrovertible proof that depression was the main cause of suicide, but human nature is far too complex for that. Though depression is the "leading causes of disability worldwide" according to the World Health Organization, not everyone who lives with it experiences suicidal ideation. Nor, according to experts, is depression by itself the main cause of suicide.

There are also other factors at work. Many people who live with depression may not even know that they're experiencing symptoms of the disorder. And so many people try to push through the pain of depression with atypical symptoms — where the person appears fine to others — that is now colloquially known as smiling depression. Then there's the fact that despite long-held cultural beliefs about suicide, not all people who die by suicide telegraph their intentions to others. Nor are all suicides planned. Impulsivity and access to lethal means are also important factors that must be considered.

This means that it's more important than ever to show up for the people in our lives.

Just because suicide is hard to predict now, doesn't mean it will always be. And new advances in technology — specifically machine learning — are bringing researchers closer to more reliably being able to recognize who is more at risk and when.

But that technology is still years away, which means that it's on us to reach out and take action when we notice warning signs in our friends and loved ones.

Making the public at large aware of hotlines and suicide prevention centers is important, but it's also essential that we recognize that not everyone will want to, or even know that they can, utilize these services. And the stigma that surrounds mental illness often makes it feel impossible to ask for help, no matter who you are.

The most important thing we can do is be present for those that we care about. It may feel strange to call up a friend just to check up on how they're doing, but the even the smallest amount of human contact can't be overstated.

Think about your own dark times — everyone has them: When it felt like it would be too much to even text a friend, what would it have been like to receive a message from them first, just making sure you're doing OK? Would you have considered it intrusive? Or would it have been a relief to have someone just be there?

Don't be afraid to talk — even if it's about your concern that the person you're reaching out to may be experiencing suicidal thoughts. Open and compassionate conversation about suicide doesn't lead to a higher risk. Instead, it allows the person who's struggling to name what's going on and share their feelings. Often, that's the first step to getting help.

If you or someone you know is struggling, know that there are immediate resources available if you're in a crisis. There are many organizations to become familiar with, including the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline 800-273-8255, the Crisis Text Line (text "HOME" to 741741), and the Trevor Project 866-488-7386.

Baby boomer grandparents.via

Baby boomer grandparents.via  A stressed mom with her head in her hands.via

A stressed mom with her head in her hands.via  A stressed mom doing laundry.via

A stressed mom doing laundry.via  Girl Illustration GIF by Valérie Boivin

Girl Illustration GIF by Valérie Boivin Jennifer Lopez Applause GIF by NBC World Of Dance

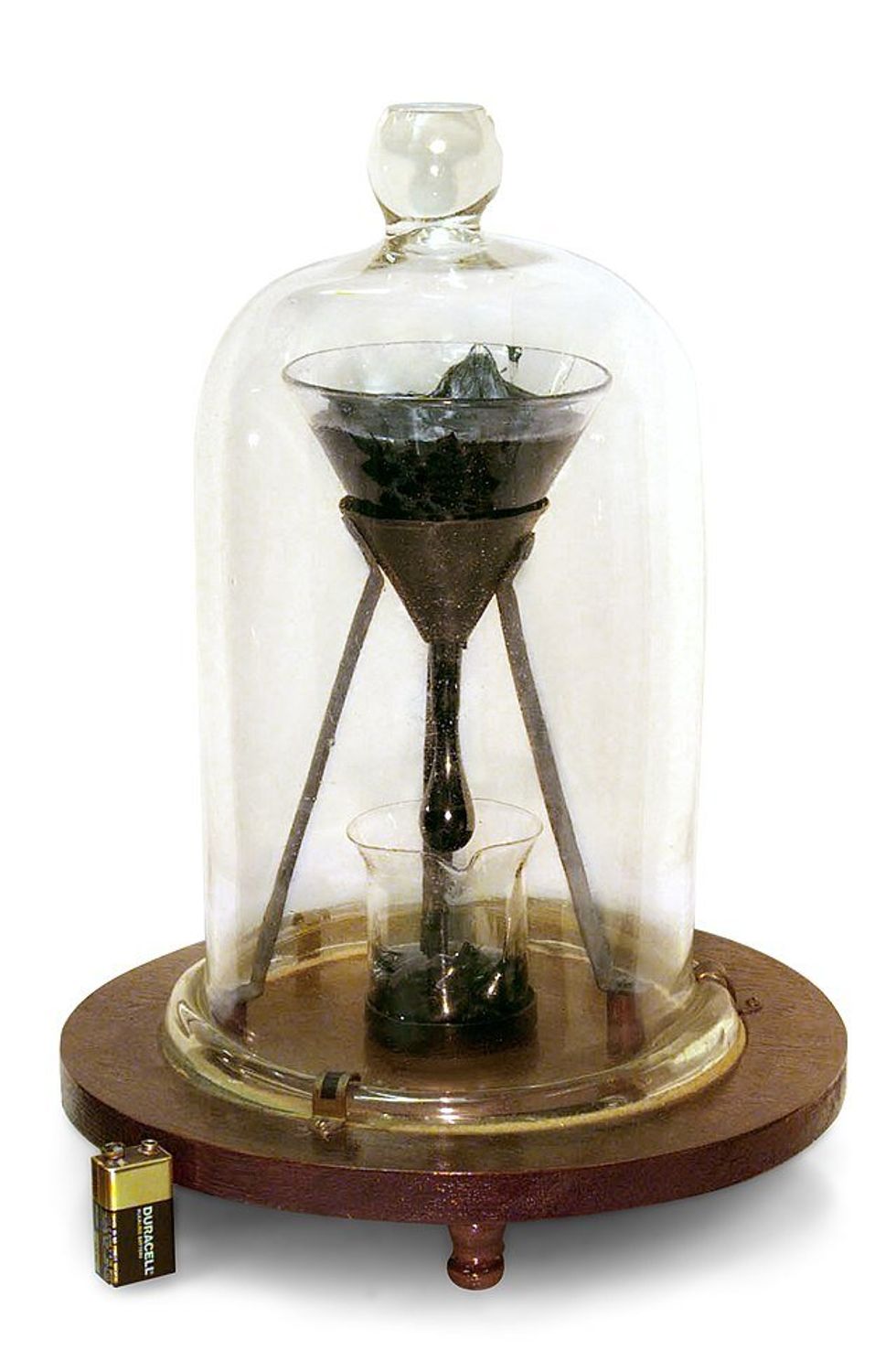

Jennifer Lopez Applause GIF by NBC World Of Dance Pitch moves so slowly it can't be seen to be moving with the naked eye until it prepares to drop. Battery for size reference.

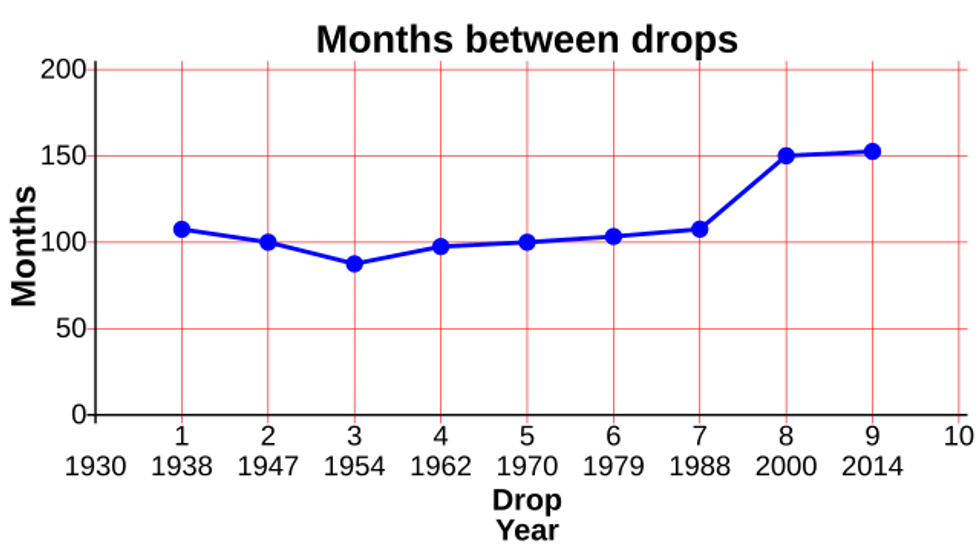

Pitch moves so slowly it can't be seen to be moving with the naked eye until it prepares to drop. Battery for size reference. The first seven drops fell around 8 years apart. Then the building got air conditioning and the intervals changed to around 13 years.

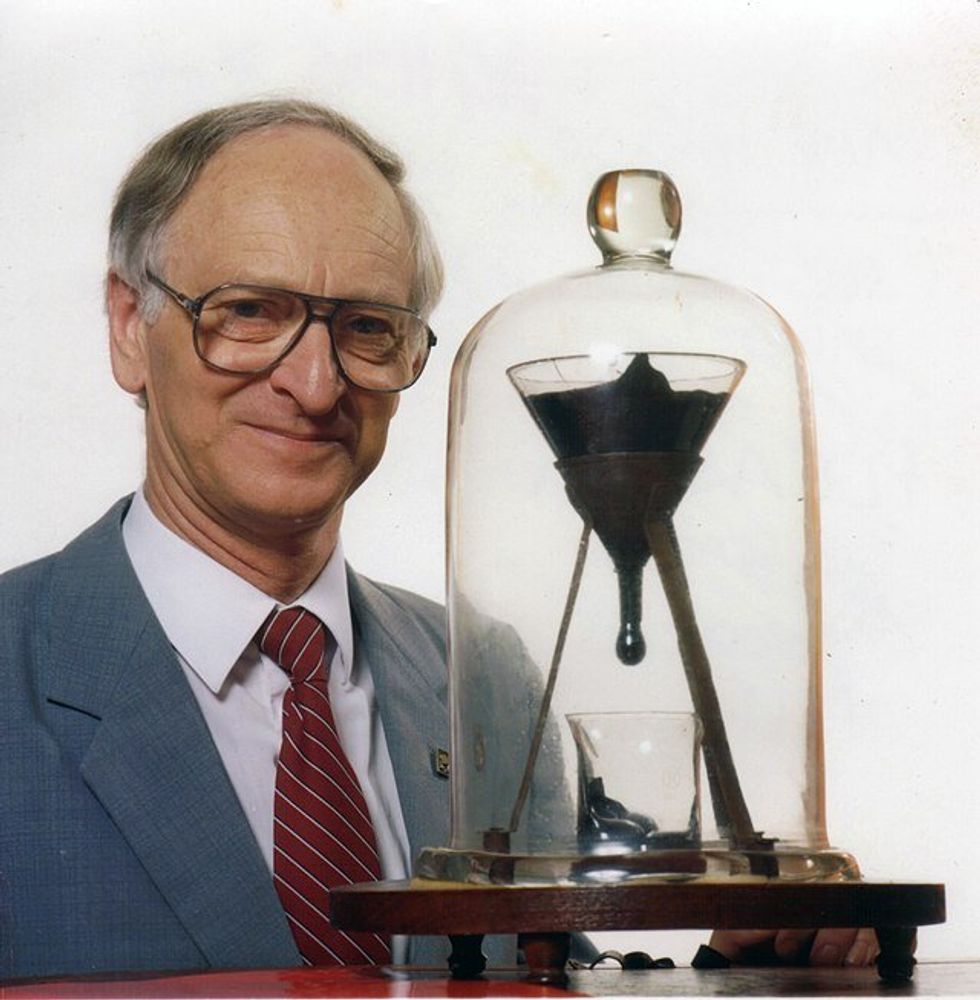

The first seven drops fell around 8 years apart. Then the building got air conditioning and the intervals changed to around 13 years. John Mainstone, the second custodian of the Pitch Drop Experiment, with the funnel in 1990.

John Mainstone, the second custodian of the Pitch Drop Experiment, with the funnel in 1990. Cat sitting on a cushion. Image via Canva.

Cat sitting on a cushion. Image via Canva. Cat sitting on a chair. Image via Canva.

Cat sitting on a chair. Image via Canva. shocked cat GIF

Giphy

shocked cat GIF

Giphy

Some kids in the '90s playing in a shopping cart.via

Some kids in the '90s playing in a shopping cart.via  A beautiful shot of a dog on a farm. via

A beautiful shot of a dog on a farm. via