"I effectively bled to death in my own hospital," said Dr. Rana Awdish.

Dr. Rana Awdish. Photo from Henry Ford Hospital.

In 2008, Awdish was seven months pregnant and just finishing up her fellowship at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit. On her last day, however, something suddenly went deeply wrong inside of her. She began to bleed into her abdomen — fast. Her body effectively crashed out. It took more than 26 units of blood products that night just to keep her alive. She would go through organ failure, respirators, even a stroke.

Ultimately, the hospital was able to save her, but unfortunately, not her baby. Later, they'd discover the cause was an undiagnosed ruptured tumor in her liver. Her recovery would take years and five major operations.

"I had to relearn to walk, speak, and do many other things I had taken for granted," said Awdish. She told her story in an article published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Today, Awdish is back at work, but the experience forced her to confront some uncomfortable truths about her job.

Doctors are trained in how to cure patients, but actually being on the opposite side of that relationship revealed something Awdish had never realized: how inadvertently hurtful even an amazing doctor's words could be. Stuck in a hospital bed, Awdish saw how seemingly normal hospital jabber could hide a mess of tiny, unseen emotional barbs.

"We're going to have to find you a new liver," someone said to her. "Unless you want to live here forever."

“You should hold the baby,” another medical staffer said.“I don’t want to be graphic, but after a few days in the morgue, their skin starts to break down, and you won’t be able to anymore, even if you change your mind.”

But in those words, she also saw her own practice as a doctor.

"I overheard a physician describe me as 'trying to die on us.' I was horrified. I was not trying to die on anyone. The description angered me," said Awdish. "Then I cringed. I had said the same thing, often and thoughtlessly, in my training."

She realized that as a doctor, she had focused on getting people healthy. Just keeping people alive was her measure of success. But actually being sick herself brought up waves of emotion.

"I realized when I sort of kept dying in the hospital is that I had all this existential angst," says Awdish. "Can we talk about how I'm dying? You see it. I know you see it. You just coded it. This feels awkward that we're not discussing it."

But at the same time, Awdish realized she had been blind to her own patients confronting similar feelings. "I remember having patients ask me, when they're diagnosed with cancer, 'But how could this have happened?' And as a doctor, I had taken that as an invitation to give them data," says Awdish. "But that's not what they were asking. It was a request for a connection."

The problem, in the end, was that empathy had taken a backseat to everything else.

When Awdish went back to work, she decided to change her entire outlook of what medicine should be.

"My experience changed me. It changed my vision of what I wanted our organization to be, to embody," she explains.

While she had received years of training in how to fight illness — years of breaking disease into digestible parts, memorizing strategies, practicing care — there hadn't been an equivalent training in how to talk to patients. She had just been more or less expected to pick it up as she went.

Awdish began working with an organization called VitalTalk, which helps train physicians in how to communicate with patients.She and a group of like-minded doctors began recruiting improv actors from around Detroit and Pittsburgh to help them rehearse how to have tough, emotional conversations.

Awdish and her colleagues did this for years as a kind of grassroots movement. Today, Henry Ford Hospital has embraced Awdish's culture of empathy.

Awdish is now part of the hospital system's new Department of Physician Communication and Peer Support. Among other things, medical staff at Henry Ford now get access to a suite of talks, apps, workshops, and courses. They might learn how to recognize anxiety or how to connect with a patient's values before prescribing therapies, says Awdish. There are even shadowing programs, where the doctors can get discreet feedback and coaching.

New hires are also taught that everyone, not just doctors, can help people in the healing process. For this, Awdish can draw examples from her own experience.

"Radiology technicians learn what a kindness it was that they stopped trying to awaken my exhausted husband to move him from my bedside for my portable X-ray — instead throwing a lead cover over him and letting him sleep," said Awdish.

Awdish says even the doctors themselves could be benefiting from the changes. Physicians might have to have multiple, very difficult conversations with patients every day. It takes an emotional toll. By equipping doctors with the tools to better connect and communicate with patients, it's helping them too.

As for whether this is working, a pilot study suggested that patients can see a difference. The hospital is now collecting big picture data and plans on publishing it.

This is a teacher who cares.

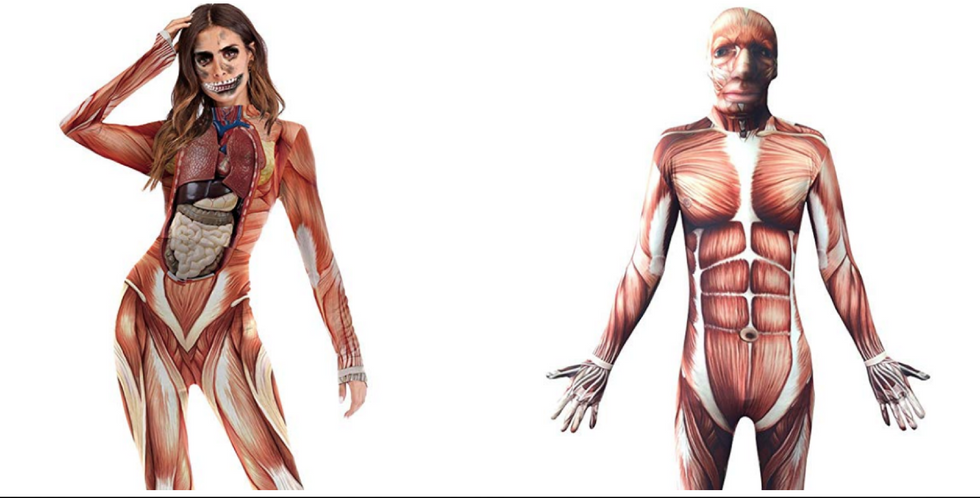

This is a teacher who cares.  Halloween costume, check.

Halloween costume, check.  Wealth Inequality is a rampant problem.

Photo by

Wealth Inequality is a rampant problem.

Photo by  Summer Fall GIF by Mark Rober

Summer Fall GIF by Mark Rober Raining Stick Figure GIF by State Champs

Raining Stick Figure GIF by State Champs Where we started.

Where we started. Paradise in the backyard

Paradise in the backyard Welcome to Whelan Design House.

Welcome to Whelan Design House. Beauty is possible!

Beauty is possible! Dads are gonna be dads.

Dads are gonna be dads.