Bob Branham was at his office on a Friday morning when he got an exciting call from a farmer offering him 40,000 pounds of green beans.

“[He] said, ‘I have a field of green beans that have to be picked right now. I have a choice. I can pick them and ship them all to you, free of charge, or I can just leave them in the field,’” Branham remembers.

Leaving them in the field would be great for his soil, the farmer explained, but he’d prefer that the produce goes to better use: feeding hungry families.

So he called Branham, who works as the Director of Produce Strategy at Second Harvest Heartland, a food bank in Saint Paul, Minnesota

These calls aren’t uncommon; in fact, they play a major role in Second Harvest Heartland and food banks’ efforts to continue providing healthy food for families in need.

40 million Americans don’t have consistent access to nutritious, healthy food, such as fruits and vegetables. This is often due to a combination of economic struggle, and the logistics of trying to find a store with affordable, fresh produce, rather than a corner store stocked with potato chips and ramen.

But the good news is, farmers — both big and small — are helping address the problem.

Surpluses - which occur frequently due to supply and demand shifts, favorable weather or the inability to sell or harvest crops in time - can leave farmers in a bind. Like the farmers Branham works with, they have to decide whether or not to donate, which introduces its own issues. After all, what can a single food bank do with 40,000 pounds of green beans?

“We [end up] getting surplus produce into food banks and we can’t use it [all] ourselves,” Branham explains. “It ends up going to waste in some way.”

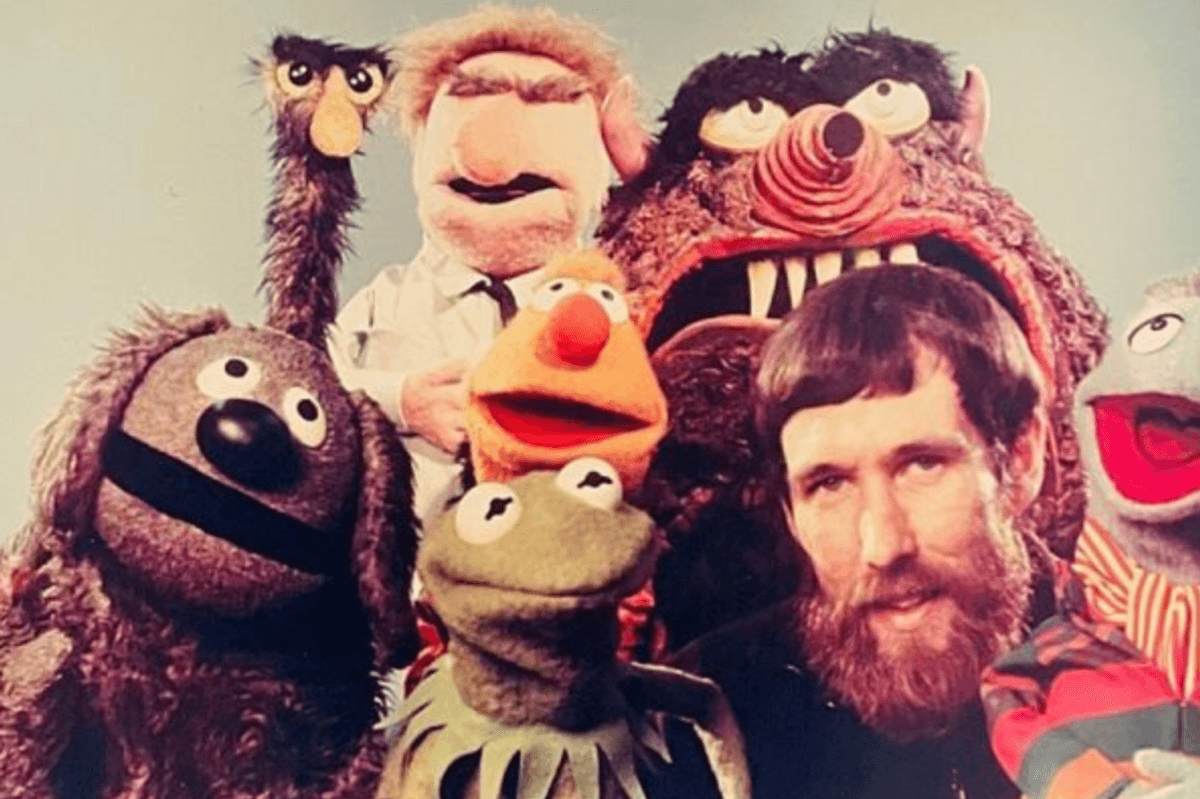

Photo by Thomas Gamstaetter/Unsplash.

If this food doesn’t go to waste, however, it could help a lot of families.

Think of it this way: The average meal weighs 1.2 lbs of food, give or take. In theory, Branham explains, 40,000 lbs of green beans could end up being about 33,000 “meals.” But since green beans aren’t themselves an entire meal, they could be combined with other rescued food, feeding upwards of a hundred thousand people.

So to ensure that surplus food gets where it’s needed most, Branham focuses on a powerful solution: produce cooperatives.

Produce co-ops, found at food banks like Second Harvest Heartland, function like a “hub” for food banks in their region. They receive donated fruits and vegetables and make sure they’re distributed to food banks that need them, rather than to locations where they’ll go to waste.

When large amounts of produce first arrive at a produce co-op, they’re first stored in a refrigerated warehouse. From there, the produce is “mixed” — packaged up with other types of fruits and veggies. The co-ops then track and ship the produce off to where it needs to go, in just the right amounts.

“That way, food banks can take on the amount of produce that they are able to distribute themselves, so they’re not wasting any either,” Branham says.

Farmers like Larry Alsum of Alsum Farms, which donates millions of pounds of surplus potatoes every year to produce cooperatives, are enthusiastic about their potential for impact.

“Nutrition for every human being is a fundamental need,” he says. “As a farmer who has been blessed to always have plenty of food myself, that [is] one of my passions in life . . . to provide food security for all.”

And for farmers like Alsum, feeding families is just one part of what makes produce co-ops great. It’s about the environmental impact, too.

“[Farmers] want to be good stewards of our land, water and resources used,” he says. “Part of this stewardship is to make sure that we keep the food waste to a minimum.”

As the Natural Resources Defense Council reports, the environmental impact of the surplus can be substantial. In fact, 21% of agricultural water use and 19% of all croplands are utilized to grow food that ultimately goes uneaten. Farmers like Alsum want to lessen this burden.

When all the food they grow is eaten, farmers ensure that every resource they use — including the water to grow their crops, the nutrients in the fertilizer that they use, and the land that they work — goes towards feeding hungry families, rather than vegetables and fruits that wilt in the fields.

With produce co-ops, it’s a win across the board — for farmers, the environment, and most importantly, families in need.

In fact, co-ops, like those at Second Harvest Heartland, have been so successful that they’re now being introduced to food banks around the country.

With the support of The Rockefeller Foundation, Feeding America now has the backing they need to bring produce co-ops to parts of the country where they don’t currently exist.

Over 200 food banks are part of Feeding America’s network, which means that the impact on food insecure families is only growing. “The more nutritious food [those families] have, the healthier they’re going to be,” Branham says. “[And then] they don’t have to trade off things like medicine or car repairs for food.”

That’s why, these days, when Branham gets a call about fruits or vegetables, he can’t help but feel hopeful.

After all, those 40,000 pounds of green beans were about much more than food — they were a profound reminder about how one farmer’s selfless act made all the difference, helping thousands of his neighbors and families throughout the Midwest.

“[That farmer] didn’t have to make that phone call,” Branham says. “[He shipped] it from his farm all the way up to me, costing him thousands of dollars, simply so I could have green beans that he could’ve left in the field.”

“That’s every day,” he continues. “That’s the story of the farmer and how their generosity is helping us do the work that we need to do.”

For more than 100 years, The Rockefeller Foundation’s mission has been to promote the well-being of humanity throughout the world. Together with partners and grantees, The Rockefeller Foundation strives to catalyze and scale transformative innovations, create unlikely partnerships that span sectors, and take risks others cannot — or will not.

A Generation Jones teenager poses in her room.Image via Wikmedia Commons

A Generation Jones teenager poses in her room.Image via Wikmedia Commons

A woman getting her nails painted.via

A woman getting her nails painted.via