Introducing hanami: the Japanese tradition that'll make you fall in love with nature.

'When cherry blossoms scatter ... no regrets.' — Kobayashi Issa

When it comes to viewing cherry blossoms, timing is everything.

Get the timing of your viewing party wrong, and all you'll see in the park are little red buds — or worse, a ground littered with the pink "snow" of fallen petals.

But get it right, and well ... just take a look.

Image by Kazuhiro Nogi/AFP/Getty Images.

Cherry blossoms bloom all over the world every spring.

If you live in Vancouver, Canada, Washington, D.C., or one of these other cities, you can see them right now at the end of March. (Go! Quickly!)

But in Japan, cherry blossoms are an even bigger deal. Their arrival generates national celebration.

The soft pink blooms, called sakura by the Japanese, only live for about 10 days every year. In Tokyo, their annual bloom usually occurs around the end of March, signaling the official start of spring.

Image by Junko Kimura/Getty Images.

Watching sakura blooms — often in the company of good friends and good food — is called hanami. And the Japanese take it very, very seriously.

During the 10- to 14-day period, hundreds of thousands of people flock to parks and gardens to enjoy picnics and gatherings and bask in the brief beauty of these bountiful blossoms.

Image by Junko Kimura/Getty Images.

Some dress up for the occasion.

Image by Yoshikazu Tsuno/AFP/Getty Images.

Others create art in honor of the season.

Sakura is one of the most popular symbols in Japanese culture, immortalized in art, stories, and this festive ice sculpture. Image by Yoshikazu Tsuno/AFP/Getty Images.

The hanami tradition is said to have begun during Japan's Nara period, when aristocrats would pass time in the spring admiring ume (plum) blossoms.

Over time, people began to associate hanami more with sakura blossoms, making springtime offerings to the Shinto spirits within the cherry trees in hopes of a good harvest to come.

These cats aren't part of a traditional offering, unless your religion is Instagram. Image by Junko Kimura/Getty Images.

In later years, Emperor Saga would hold feasts for his imperial court under the sakura blooms, drinking sake and listening to sakura-inspired poetry.

By the start of the Edo period, all levels of Japanese society were celebrating cherry blossom season.

Image by Chris McGrath/Getty Images.

Modern hanami parties don't have to happen during the day. Evening gatherings — when the blossom-laden branches are lit by lanterns or soft candlelight — are also very popular (and pretty magical).

Image by Chris McGrath/Getty Images.

Because even on a rainy evening, sakura blossoms put on a show.

Image by Chris McGrath/Getty Images.

Though, to be fair, it can get a little crowded.

In 2015, a record 19.73 million overseas tourists visited cherry blossom hotspots in at least 18 Japanese cities.

Image by Chris McGrath/Getty Images.

Demand for space is so high, some companies wanting to throw hanami parties might send employees down hours before to reserve a spot.

Image by Chris McGrath/Getty Images.

One of the reasons cherry blossoms draw so much attention in Japanese culture is their natural impermanence.

Like all flowers, cherry blossoms are doomed to wither eventually. In Japanese culture this is seen as a metaphor for the ephemerality of life, an idea embodied in the unique concept of mono no aware.

Image by Koichi Kamoshida/Getty Images.

"Mono no aware" loosely translates to English as "an empathy toward things." It's an acknowledgement that all things in life (even life itself) are temporary.

If this realization makes you sad, that's OK. It is supposed to. Part of mono no aware is acknowledging the soft sadness that comes along with our lives. For the sakura blossoms to bloom, they must also die. It is meant to be a wistful sadness, not an overwhelming one.

Image by Kazuhiro Nogi/AFP/Getty Images.

I like to think of mono no aware, and sakura blossoms in general, as a reminder for all of us to be fully present in life's moments as they happen.

To savor the beautiful, the sad, and the fleeting — as both we and they will eventually float away.

"The cure for / this raucous world ... / late cherry blossoms" — 17th century Japanese poet Kobayashi Issa

A group of friends chatting wearing masks.via

A group of friends chatting wearing masks.via

A boy drawing on an iPad.

A boy drawing on an iPad.

a man sitting at a desk with his head on his arms Photo by

a man sitting at a desk with his head on his arms Photo by  Can a warm cup of tea help you sleep better? If you believe it, then yes. Photo by

Can a warm cup of tea help you sleep better? If you believe it, then yes. Photo by

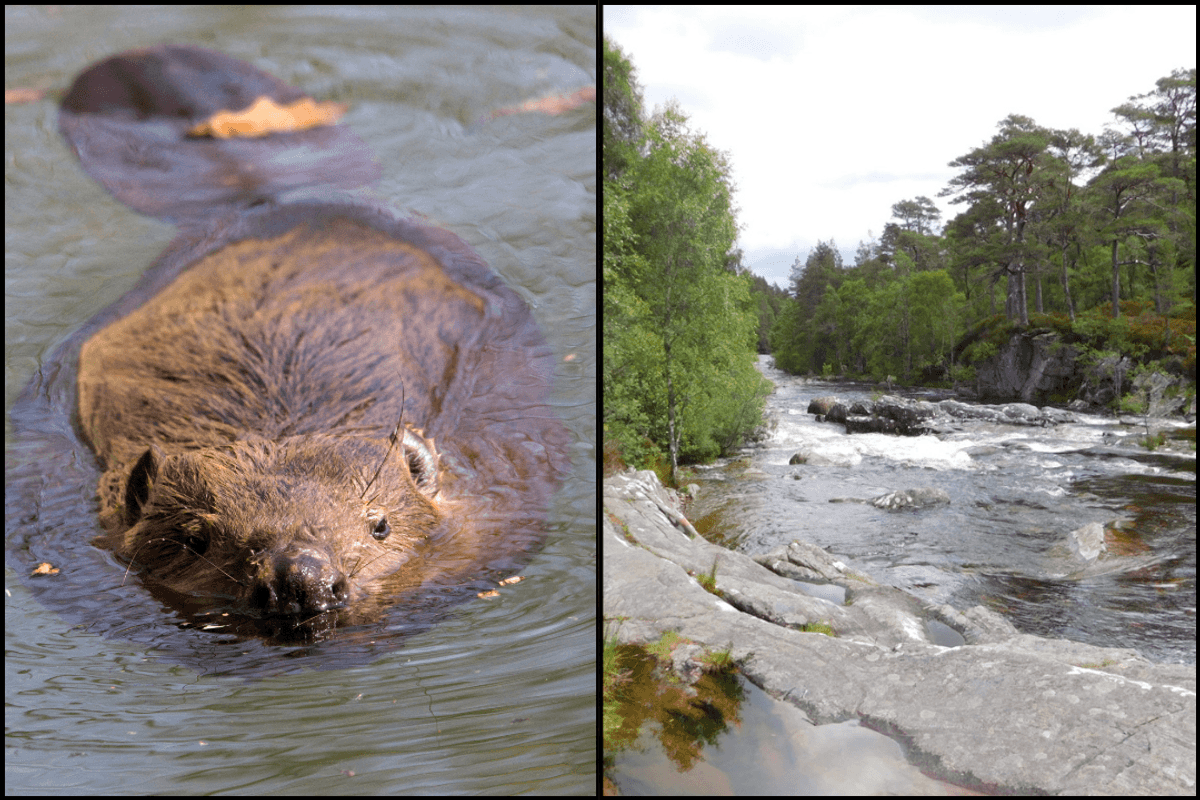

Dams have dramatic impacts on the surrounding ecosystem.

Dams have dramatic impacts on the surrounding ecosystem.  Beavers aren't just cute and charismatic.

Beavers aren't just cute and charismatic.