Barely three months after Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, allowing for the relocation of anyone on the West Coast deemed a threat to national security.

Soon, nearly 100,000 people of Japanese ancestry (many born in America and half of them children) were assigned identification numbers and loaded into buses, trains, and cars with just a few of their belongings. After a brief stay at temporary encampments, they were moved to 10 permanent, but quickly constructed, relocation centers — better known as internment camps.

Departing for relocation. Photo by Ansel Adams/Library of Congress.

In 1943, renowned photographer Ansel Adams visited one of the camps.

Adams was best known for his landscape photography, with his work appearing in galleries and museums across the country. But he welcomed the opportunity to see and capture life at the Manzanar War Relocation Center in the fall of 1943.

Photo by Ansel Adams/Library of Congress.

These are just a few dozen of his photos capturing the unthinkable experience of being a prisoner of war in your own country.

Life at the internment camp was hard on the body and spirit.

1. Nestled in Owens Valley, California, between the Inyo and Sierra Nevada mountains, the camp faced harsh conditions.

Photo by Ansel Adams/Library of Congress.

There were relentless blasts of desert dust, heat during the day, and punishingly cold temperatures at night.

2. There were 10,000 people crowded into 504 barracks at Manzanar, covering about 36 blocks.

Photo by Ansel Adams/Library of Congress.

3. Each barrack was divided into four rooms, shared toilets, showers, and a dining area, offering families little to no privacy or personal space.

Photo by Ansel Adams/Library of Congress.

Furnishings and creature comforts were sparse. Just a cot, a straw-filled mattress, and blankets. Up to eight individuals shared a 20-by-25-foot room.

4. Due to the severe emotional toll and inadequate medical care, some Japanese Americans died in the camps.

Marble monument with inscription that reads "Monument for the Pacification of Spirits." Photo by Ansel Adams/Library of Congress.

Others, including some at Manzanar, were killed by guards, allegedly forresisting orders.

Though he was a civilian employed by the military, Adams was able to capture aspects of the camp that the government didn't want depicted in his work.

5. The housing section at Manzanar was surrounded by barbed wire and patrolled by military police.

Photo by Ansel Adams/Library of Congress.

But shots of armed soldiers, guard towers, or barbed wire weren't allowed, so Adams worked around it. Instead, he captured these subjects in the background or the shadows.

6. So while he couldn't take a photo of the guard tower, he took one from the top of it.

Photo by Ansel Adams/Library of Congress.

As serious as conditions were, internees attempted to make the most of an unimaginable situation.

7. They were allowed to play organized sports, like volleyball.

Photo by Ansel Adams/Library of Congress.

8. Baseball games were popular too.

Photo by Ansel Adams/Library of Congress.

To maintain order, teams of players from each center were allowed to travel from camp to camp to play ball.

9. Churches and boys and girls clubs were established.

A Sunday school class at the internment camp. Photo by Ansel Adams/Library of Congress.

10. There were singing groups.

The choir rehearses. Photo by Ansel Adams/Library of Congress.

11. And even a YMCA.

Photo by Ansel Adams/Library of Congress.

In the face of adversity, everyone did their best to stay busy.

12. Kids went to school...

Photo by Ansel Adams/Library of Congress.

13. ...had recess...

Photo by Ansel Adams/Library of Congress.

14. ...and studied for uncertain futures, all behind barbed wire.

Students listen to a science lesson. Photo by Ansel Adams/Library of Congress.

15. The adults worked inside Manzanar. Some maintained the dusty, arid fields.

There were 5,500 acres of land for agriculture at Manzanar. Photo by Ansel Adams/Library of Congress.

16. They grew crops like leafy greens and squash.

Photo by Ansel Adams/Library of Congress.

17. Or raised cattle.

Photo by Ansel Adams/Library of Congress.

18. Others worked as welders...

Photo by Ansel Adams/Library of Congress.

19. ...nurses...

A nurse tends to babies at the orphanage. Photo by Ansel Adams/Library of Congress.

20. ...scientists...

Photo by Ansel Adams/Library of Congress.

21. ...or shopkeepers.

Photo by Ansel Adams/Library of Congress.

22. Workers earned $12 to $19 a month. Some pooled their earnings to start a general store, newspaper, and barbershop.

Photo by Ansel Adams/Library of Congress.

By the end of the war, more than 11,000 Japanese Americans had been processed through the Manzanar camp.

And despite being held for supposedly posing a threat to national security, not one Japanese American was charged with espionage.

Photo by Ansel Adams/Library of Congress.

The Manzanar camp closed in 1945. Japanese Americans returned to neighborhoods and homes they barely recognized. And 45 years later, they received a formal apology.

In 1988, after a decade-long campaign, Congress passed The Civil Liberties Act, which required the government to pay $20,000 in reparations to each internment camp survivor. In 1990, the first of nine redress payments was made. A 107-year-old reverend, Mamoru Eto, was the first to receive his payment. Later, President George H.W. Bush delivered a formal apology.

"I took that as evidence that — in spite of the things the government did — this is a country that was big enough to say, 'We were wrong, we're sorry," one survivor told the BBC.

By standing up to hysteria and xenophobia — and refusing to forget this unforgivable era in American history — we can continue to do right by the thousands of Americans put in an unthinkable situation.

These photos remind us of why we will never go back to a place like that again.

Millennial mom struggles to organize her son's room.Image via Canva/fotostorm

Millennial mom struggles to organize her son's room.Image via Canva/fotostorm Boomer grandparents have a video call with grandkids.Image via Canva/Tima Miroshnichenko

Boomer grandparents have a video call with grandkids.Image via Canva/Tima Miroshnichenko

In a 4-day model, kids often (but not always) receive less instructional time. Photo by

In a 4-day model, kids often (but not always) receive less instructional time. Photo by

Worried mother and children during the Great Depression era. Photo by Dorthea Lange via Library of Congress

Worried mother and children during the Great Depression era. Photo by Dorthea Lange via Library of Congress  A mother reflects with her children during the Great Depression. Photo by Dorthea Lange via Library of Congress

A mother reflects with her children during the Great Depression. Photo by Dorthea Lange via Library of Congress  Families on the move suffered enormous hardships during The Great Depression.Photo by Dorthea Lange via Library of Congress

Families on the move suffered enormous hardships during The Great Depression.Photo by Dorthea Lange via Library of Congress

Play Go GIF

Play Go GIF  Things were different when we were kids.

Things were different when we were kids.  imagination GIF

imagination GIF

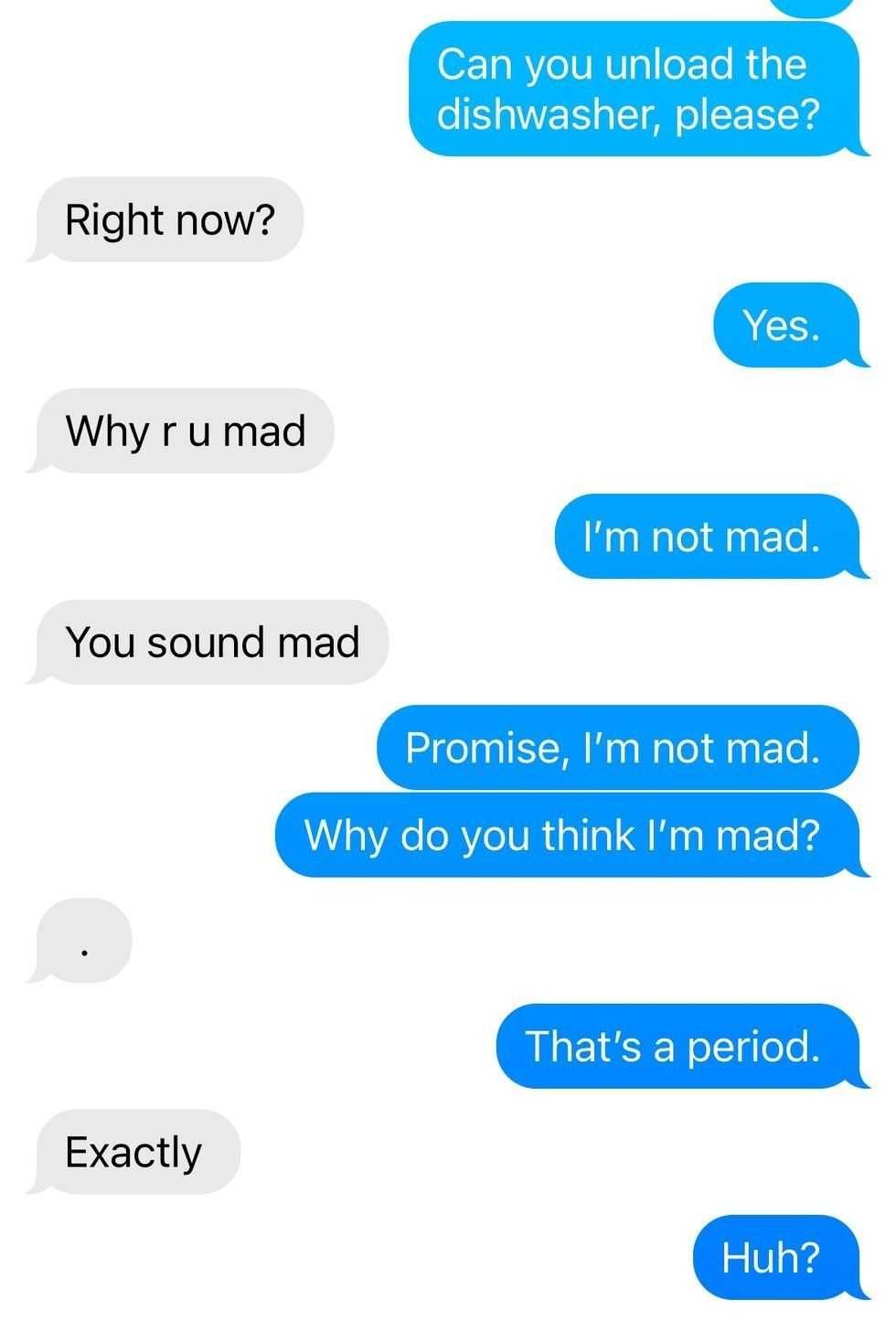

How can we see a period so differently?Photo credit: Annie Reneau

How can we see a period so differently?Photo credit: Annie Reneau  "Period!" means period. An actual period means nothing.

"Period!" means period. An actual period means nothing. Mic drop.

Mic drop.  A period is just a period. Period.

A period is just a period. Period.