I asked this kid what she wanted to be when she grew up. She said, 'Nothing.'

While education isn't an all-encompassing solution for refugee kids, it can make a big difference.

"What do you want to be when you grow up?"

When you ask a lot of kids this question, they usually have quick answers. They want to be doctors, artists, firefighter ... you name it, they'll dream it up. Kids have pretty awesome (and hilarious) ambitions.

Most kids, that is.

When I asked Zeinab, a 9-year-old girl living at the Mosaab al-Telyani refugee camp in Lebanon, this question, her answer had a completely different tone.

"I don't want to be anything. I won't become anything," Zeinab said

Zeinab, 9 years old on her first day at the program. All photos taken by the author, used with permission.

Zeinab is one of those kids you'd expect to be at the top of her class.

Unlike the other kids in her school, she is very quiet and often sits by herself. She's exceptionally thoughtful and beyond her years in education. I imagine she'd be the one raising her hand all the time at an American elementary school, the one acing vocabulary and math tests.

But at the Mosaab al-Telyani camp school, Zeinab rarely attends class. She has even said that she plans to drop out of school completely when she turns 13.

Zeinab has been assured for years that she would not become anything in life.

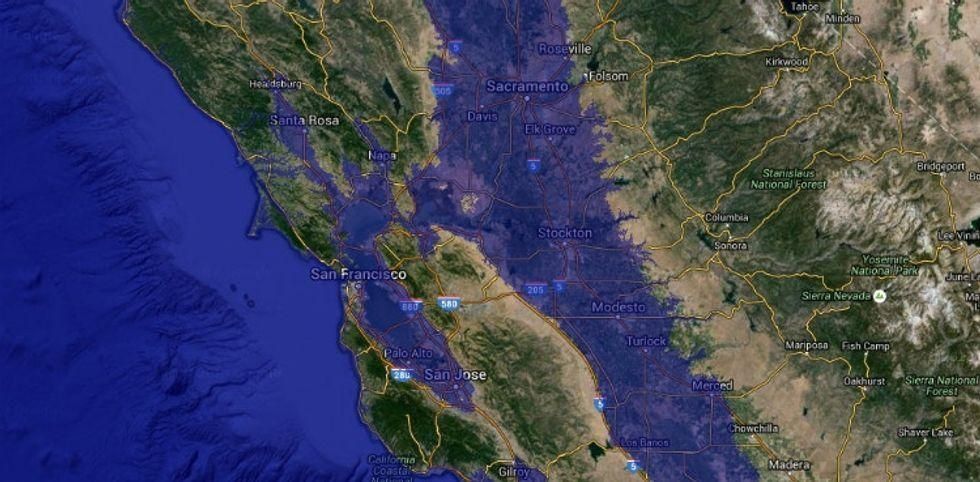

She had no hope for a life different from the one she was living, and her weak, almost nonexistent, education hadn't encouraged ambition. She had migrated from Syria to Lebanon over two years ago and lost both her parents and all her family members to the war. She lives at an orphanage in the Mosaab al-Telyani camp, which is right across the border from Syria in Beqaa Valley, Lebanon. It's home to hundreds of Syrian refugees. Zeinab is expected to marry in her teenage years in order to survive.

Zeinab writes her name in English.

Many Syrian refugee children like Zeinab miss years of school and receive little to no education after they leave their home countries. The UNHCR found last year that 66% of the 80 refugee children they interviewed in Lebanon did not attend school. And a World Bank report revealed that failure and dropout rates among Syrian children are now almost twice the national average for Lebanese children.

While education is certainly not an all-encompassing solution for refugee kids like Zeinab, it can make a big difference.

The Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre reports that 9,500 people a day — approximately one family every 60 seconds — are being displaced in Syria. The average global displacement for all refugees is 17 years, and it's likely that for Syrians, the time period will be longer. So while the proportion of the refugee crisis is unprecedented — a generation without education is a lost generation — the impact of quality education could be huge.

A recent Human Rights Watch study concluded that ensuring Syrian refugees have education will reduce the risks of early marriage and military recruitment and will increase their earning potential. Most importantly, education will shape Syrian youth to tackle the challenges they will face rebuilding their country or adjusting to unpredictable futures.

For three months, Zeinab was part of an education project that hoped to improve basic language and math skills for children with significant gaps in their education.

The program was aimed at helping these kids eventually enter the Lebanese public school system, but it was also about instilling hope and reinvigorating ambition in a generation that seems to have given up. The classrooms became safe spaces not only for education but also for building self-esteem and inspiring dreams for the future.

When the program ended, I asked Zeinab the same question again: "What do you want to be when you grow up?"

This time she had an answer ready: "I want to be a teacher."

Zeinab, on her last day of the program.

The more passionate you are about your goals, the more secretive you should be.

The more passionate you are about your goals, the more secretive you should be.  People with dementia tend to remember distant memories and forget recent ones.

People with dementia tend to remember distant memories and forget recent ones. All the workers in a dementia village are trained in memory care.

All the workers in a dementia village are trained in memory care. Kamikatusu's recycling techniques are well worth the effort.

Kamikatusu's recycling techniques are well worth the effort.  The inside of Kamikatsu's Zero Waste Center.

The inside of Kamikatsu's Zero Waste Center.  How to recycle boxes and other cardboard goods.

How to recycle boxes and other cardboard goods.  Give radical recycling a try.

Give radical recycling a try.  Raise that top dishwasher rack to the roof!

Photo by

Raise that top dishwasher rack to the roof!

Photo by  How it feels to learn you've been using your dishwasher wrong for yaers.

How it feels to learn you've been using your dishwasher wrong for yaers.