How the U.S. put an end to plane hijacking and why gun reform advocates should take note.

As thousands across the nation prepare to take to the streets on March 24, 2018, for The March for Our Lives, we're taking a look at some of the root causes, long-lasting effects, and approaches to solving the gun violence epidemic in America. We'll have a new installment every day this week.

At one point in this country, a plane was hijacked at the rate of once a week.

Between 1968 and 1972, (a period that writer Brandon I. Koerner dubbed the "golden age of hijacking"), more than 130 airplanes were hijacked. The practice was so prevalent, sometimes there would be more than one incident a day.

Not unlike our current mass shooting epidemic, skyjacking — as it came to be known — was a problem so complex and frequent that the American government, passengers, and even airlines themselves began to think of it as just a standard risk of air travel. Yet between the mid-1970s and 9/11 (and again after 9/11), skyjacking virtually ceased to exist.

What changed? And how did it get so bad in the first place? Through eight jaw-dropping facts, I'll walk you through some of Koerner's account of this incredible time in American history that wasn't very long ago — and what gun violence prevention advocates can learn from it.

Photo by Scott Olson/Getty Images.

1. Plane hijacking wasn't a routine occurrence in the U.S. until 1961, when all of a sudden, people wanted a quick escape to Cuba.

The hijackings began not long after the end of the Cuban revolution. U.S. and Cuban relations weren't strong at the time. Some saw hijacking as the only way to return to their home country or as a one-way ticket to what they perceived as a kind of "socialist Club Med."

Hijackers would board flights and demand to be taken to Havana. At the time, the airlines and the FAA told pilots and crew not to argue or take any heroic action, but instead to deliver on the hijackers' demands and take them where they asked.

Trips to Cuba became so frequent that pilots were given Spanish phrase cards to help communicate with the Spanish-speaking hijackers.

The Paseo de Marti (formerly Prado Boulevard) in Havana, circa 1960. Photo by Three Lions/Getty Images.

2. Hijacking was so common, it became a major theme on TV shows and movies.

Monty Python performed a sketch about it, and planes became a high-stakes setting for many a TV drama and film. Time magazine even wrote a piece in their travel section on what to do if your plane is hijacked. Keep that one in your carry-on.

3. What did Castro think about all these unsolicited arrivals? He wasn't too pleased.

Castro didn't exactly roll out the red carpet for the giant planes and wannabe heroes landing in his country. Koerner, author of "The Skies Belong to Us," shared the two most common fates of hijackers in an interview with CNN:

"One, you would be put in a South Havana dormitory called Hijacker House, where you were given about 16 square feet of living space with a cot, and they give you 40 pesos a month, (and) you kind of have to fend for yourself. It was a really awful life.

And if the government really didn't like you — for example, if you were violent on board the plane or if you robbed any of the passengers — they would actually send you to these gulags in the south of the country where you would harvest sugar cane. And the conditions there were just absolutely nightmarish."

4. In 1969, one hijacker realized there were places to go other than Cuba, opening up a literal world of trouble.

On the run from a military court martial, Raffaele Minichiello, an Italian immigrant and U.S. Marine, decided to flee to his home country rather than stand trial. He hijacked a plane heading from Los Angeles to San Francisco, let passengers out in Denver, then asked to fly to New York. When they got to the Big Apple, Minichiello (in so many words) said "Gotcha! I actually want to go to Rome." FBI agents tried to stop him in New York, but Minichiello fired a round into the fuselage and they backed off. After stopping again in Maine and Ireland, Minichiello made it to Rome.

His "successful" journey inspired other hijackers to think big, requesting rides to North Korea and Algeria. Some began asking for money and gold bars.

Minichiello was arrested in Rome, on Nov. 1, 1969. Photo by AFP/Getty Images.

5. While the hijackings were a scary, dangerous nuisance, the FAA used their political weight to prevent any legislation from passing.

Airlines were booming high-tech businesses at the time. The FAA did everything they could to keep them happy. Airport security was nonexistent because airlines thought no one would want to deal with the inconvenience. They pushed back against any legislation calling for metal detectors or physical searches.

Speaking on behalf of the FAA at a congressional hearing in 1968, staffer Irving Ripp said, "It's an impossible problem short of searching every passenger. If you've got a man aboard that wants to go to Havana, and he has got a gun, that's all he needs."

A view of the Trans World Airlines Terminal in New York, circa 1962. Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images.

6. The FAA did manage to establish a task force to come up with solutions. They solicited ideas from the public and they were, well, interesting.

Ideas from concerned citizens included forcing everyone on the plane to wear boxing gloves, building a fake Havana airport in Miami so planes could land there and hijackers could be arrested by American agents, installing trap doors near the cockpit, and even playing the Cuban national anthem before flights to see if anyone knew the words.

Oh, and the whole "build a fake airport" idea was actually seriously considered at one point. (Too expensive.)

7. A psychologist and hijacking task force member dug into the backgrounds of the hijackers to help him screen potential threats.

His name was John Dailey, and he examined everything from hijackers' departure cities to clothing and methods of payment. Eventually he created a checklist to help weed out potential threats from a sea of passengers and discreetly pull aside a few for additional screening.

The FAA allowed Dailey to test his method, and it was successful. However, it relied heavily on gate agents and not trained security personnel.

The American Boeing 707 circa 1958. Photo by Reg Speller/Fox Photos/Getty Images.

8. What finally made the FAA change their tune? The threat of mass casualties — and legal issues.

On Nov. 10, 1972, three hijackers threatened to crash Southern Airways Flight 49 into a nuclear research reactor near Knoxville, Tennessee, if they didn't receive $2 million. The airline came up with the money, but the flight continued (with a few stops and delays) all the way to Havana, where the hijackers were put in jail.

Realizing the planes could be used as weapons, the threat of loss of life onboard and mass casualties on the ground was enough to move the FAA and the government to act.

Starting Jan. 5, 1973, the FAA put mandatory screenings in place for all airplane passengers. And despite the FAA's concerns, most people didn't seem to mind.

Security guards inspect passengers at a security checkpoint in London, 1975. Photo by Evening Standard/Hulton Archive/Getty Images.

Our country transitioning from hundreds of hijackings to hardly any was no accident. It's a reminder of what can happen when the government takes control back from big business and lobbying organizations.

Yes, hijackings still occurred after 1973, but they were significantly less frequent and often ended without incident.

Like Southern Airways Flight 49, the attacks on September 11 forced swift, comprehensive security changes to prevent similar attacks. While the changes have been frustrating or cumbersome at times, they've been successful.

Gun violence is an issue the gun lobby believes is impossible to solve. The airlines thought screening would ruin their business, so they fought it tooth and nail while passengers were actually terrorized. The NRA and the politicians they support seem to think mass shootings are the price we pay to maintain our Second Amendment rights. But there has to be a better way — particularly one that doesn't center on selling more guns.

If we can put an abrupt end to the "golden age of hijacking," surely we can work together to put an end to this devastating era of widespread gun violence. Don't believe anyone who says commonsense policy changes won't work. They already have.

Photo by Spencer Platt/Getty Images.

For more of our look at America's gun violence epidemic, check out other stories in this series:- The next time someone blames mass shootings on mental illness, send them this.

- Parkland kids are changing America. Here are the black teens who helped pave their way.

- Dear America: Kids doing active-shooter drills is not normal.

- Answer 3 questions to find out which gun violence action plan is right for you.

And see our coverage of to-the-heart speeches and outstanding protest signs from the March for Our Lives on March 24, 2018.

A father does his daughter's hair

A father does his daughter's hair A father plays chess with his daughter

A father plays chess with his daughter A dad hula hoops with his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad hula hoops with his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. A dad talks to his daughter while working at his deskAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad talks to his daughter while working at his deskAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. A dad performs a puppet show for his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad performs a puppet show for his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. A dad walks with his daughter on his backAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad walks with his daughter on his backAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. a dad carries a suitcase that his daughter holds onto

a dad carries a suitcase that his daughter holds onto A dad holds his sleeping daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad holds his sleeping daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. A superhero dad looks over his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A superhero dad looks over his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. A dad takes the small corner of the bed with his dauthterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad takes the small corner of the bed with his dauthterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. "You are yourself drunk, you idiot!"

"You are yourself drunk, you idiot!" "People like you bring shame to this country."

"People like you bring shame to this country." "I’m glad there are people like this lady who aren’t afraid to stand up to bullies."

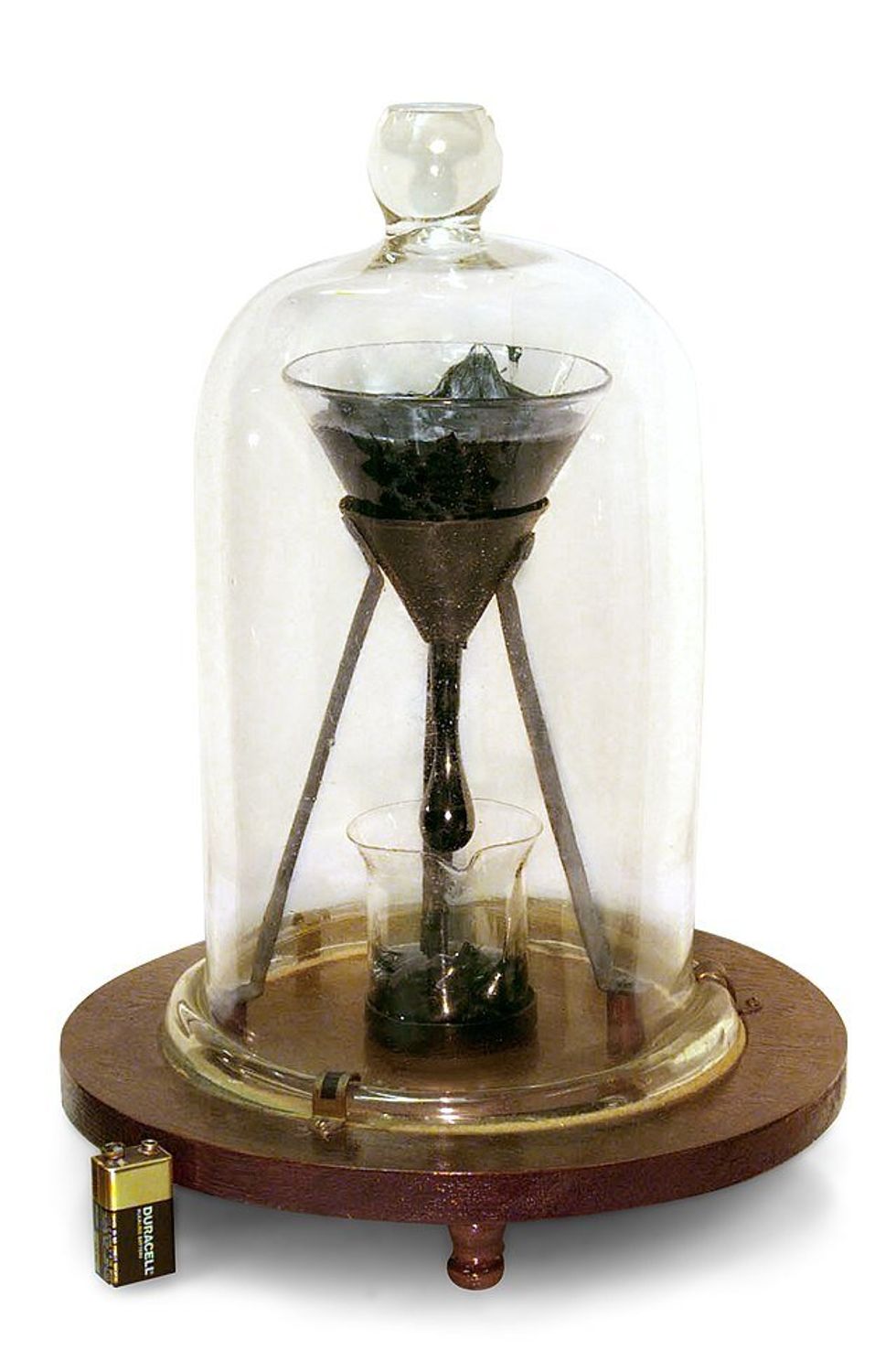

"I’m glad there are people like this lady who aren’t afraid to stand up to bullies." Pitch moves so slowly it can't be seen to be moving with the naked eye until it prepares to drop. Battery for size reference.

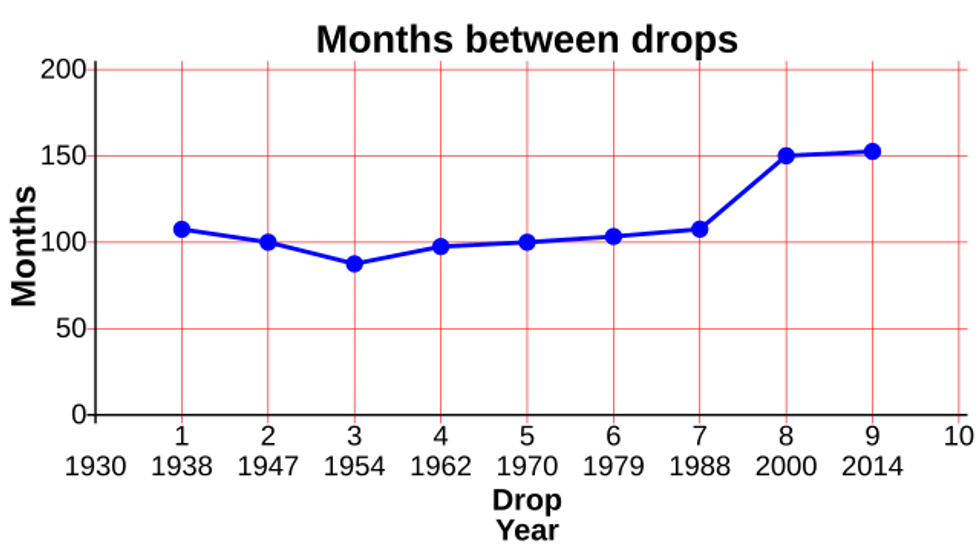

Pitch moves so slowly it can't be seen to be moving with the naked eye until it prepares to drop. Battery for size reference. The first seven drops fell around 8 years apart. Then the building got air conditioning and the intervals changed to around 13 years.

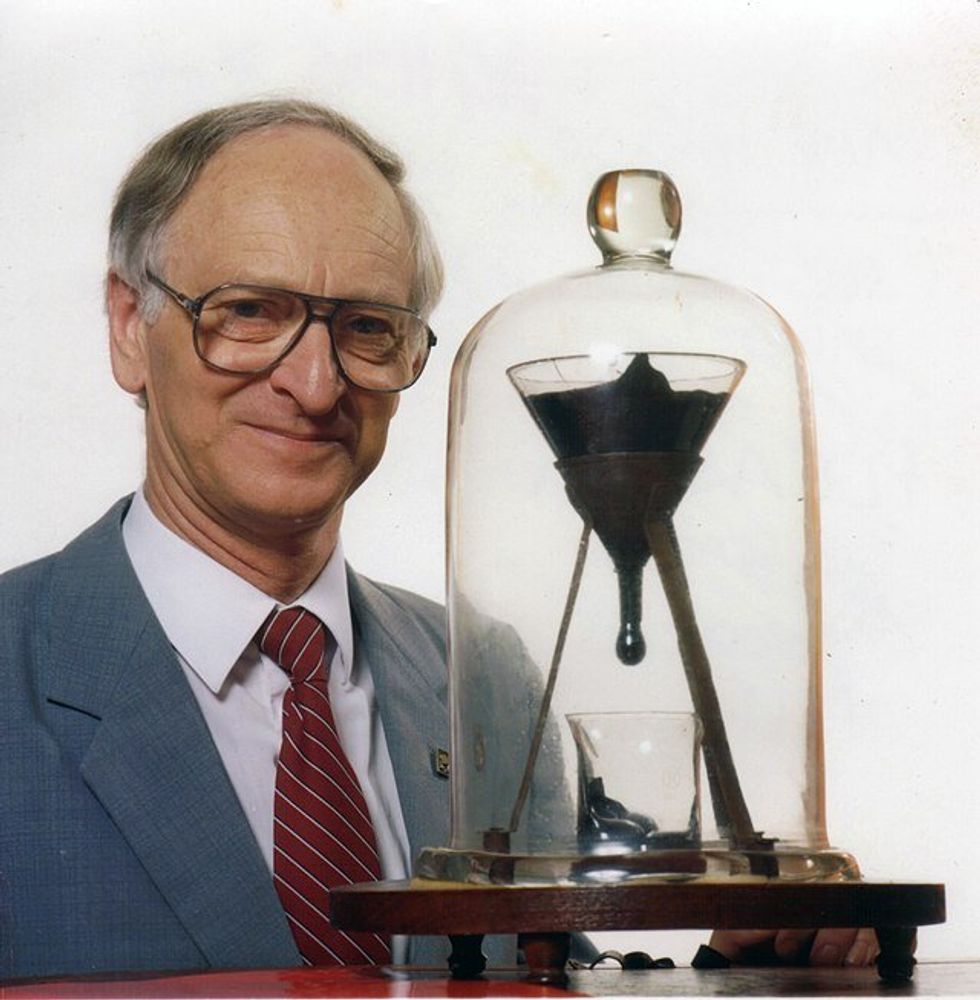

The first seven drops fell around 8 years apart. Then the building got air conditioning and the intervals changed to around 13 years. John Mainstone, the second custodian of the Pitch Drop Experiment, with the funnel in 1990.

John Mainstone, the second custodian of the Pitch Drop Experiment, with the funnel in 1990. boy in green sweater writing on white paper

Photo by

boy in green sweater writing on white paper

Photo by  person using pencil

Photo by

person using pencil

Photo by

Well Done Clapping GIF by MOODMAN

Well Done Clapping GIF by MOODMAN