Courtney Peters-Manning was sick of complaining. She wanted to do something.

The results of the election had surprised and unnerved her, and reading her social media feed felt like running in circles.

"I was getting really frustrated with just the Facebook algorithm showing me everything from people who already agreed with me, and I felt like I needed to do something concrete," says Peters-Manning, a New Jersey attorney.

Facebook did, however, serve up one key piece of useful advice. Shortly after Election Day, Peters-Manning stumbled on a post about She Should Run, a nonpartisan, Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit organization that encourages and trains women to run for office. She joined the group's candidate incubator, which she says helped her crystalize her thinking and vision while giving her the confidence to firm up her plans.

The statehouse in Trenton, New Jersey. Photo by Marion Touvel/Wikimedia Commons.

Since then, she's been networking furiously across her county, where she hopes to run — and where currently only two of seven officeholders are female.

"My husband is really excited for me, and he’s ready to step up and do whatever he has to do to make it happen for me," she says.

According to She Should Run co-founder Erin Loos Cutraro, the group saw a surge of interest after Nov. 8 from women like Peters-Manning who responded to the shocking defeat of the nation's first major-party female nominee with a feeling of urgency to act.

Prior to November, the organization offered support to 100-200 new women per month. Since Election Day, more than 6,000 women have signed up for the group's incubator.

"We know that women, when they run, win at the same rate as men, so very simply, we need more women running," Cutraro says.

She Should Run was founded in 2008, initially to study the challenges to achieving gender equity in public office.

Photo by Ryan McBride/Getty Images.

After surveying women and analyzing races across the country, Cutraro and her co-founders concluded that much of the research, which was conducted on women in the business community, applied to women in politics as well — particularly the finding that, unlike most men, most women don't apply for jobs unless they can check every requirement.

"There’s a saying: ‘Either you’re at the table or you’re on the menu.’ So I think we need to be at the table."

— Courtney Peters-Manning

"A lot of women will question their qualification," Cutraro says. One goal of the incubator is to disabuse prospective candidates of the idea that they need to be an expert in everything in order to start the process.

For Chelsea Wilson, joining the She Should Run incubator has given her a community of like-minded women to talk about the fears and risks of running for office.

She Should Run "really meets women where they’re at," says Wilson, an Oklahoman and Cherokee Nation member who works on Native American economic development. "That’s one of the best things about it."

Wilson hopes to return to Oklahoma to run for local office, where she plans to continue her work representing Native interests and advocating equality for women and girls.

Recruiting more women for office is more than an issue of fairness, according to She Should Run.

"If we want the smartest policies possible, we can’t possibly expect to get there if we’re not tapping the talents of half the population in our country," Cutraro says.

Kamala Harris, freshman U.S. senator from California, takes the oath of office. Photo by Aaron P. Bernstein/Getty Images.

One of the organization's biggest challenges is getting women who are working on causes in their home communities to see their own power and potential for effecting change on those issues in office. The group has ambitious expansion plans, including adding staff in the coming year to help manage the onrush of interest and expanding its technological capability to reach more women virtually.

The group also aims to ensure the interests of half of the population are fairly represented at the highest — and lowest — levels of American government.

"There’s a saying: ‘Either you’re at the table or you’re on the menu.’ So I think we need to be at the table," Peters-Manning says.

For many of She Should Run's staff and clientele, 2016 demonstrated the brutality that women can subjected to on the campaign trail. Cutraro notes, however, that there are hundreds of offices at the state, local, and municipal levels where women can run issue-based campaigns without being subjected to a barrage of personal opposition research.

Chelsea Wilson with She Should Run's "All-Barbie female ticket." Photo via Chelsea Wilson.

Still, for those who are interested in running for higher office, the program hopes to embolden those nervous about meeting that brutality head-on to emerge clear-eyed and unafraid.

On that count, it's succeeding.

"I know that it’s going to require a lot of courage," Wilson says, "more courage than I thought it would even a year ago. And a lot of hard work. But it’s definitely not something I’m going let anyone intimidate me about, and it’s something that will be worth it, no matter what the outcome of a run for me would be."

This is a teacher who cares.

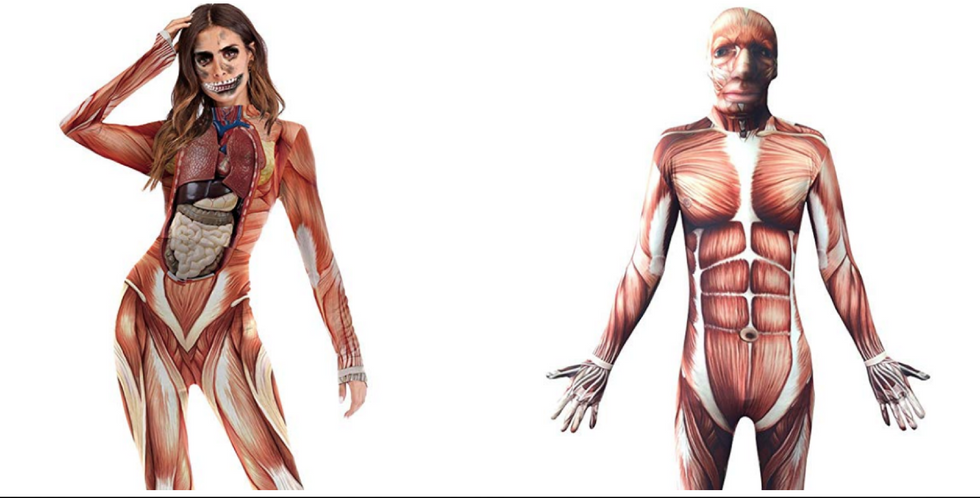

This is a teacher who cares.  Halloween costume, check.

Halloween costume, check.  Patagona has always done a great job taking care of its employeesYukiko Matsuoka/Flickr

Patagona has always done a great job taking care of its employeesYukiko Matsuoka/Flickr While nursing my baby during a morning meeting the other day after a…

While nursing my baby during a morning meeting the other day after a… Not sure if Dwight Schrute would be as accomodating.

Not sure if Dwight Schrute would be as accomodating. "The conditions had turned WHAT?"

"The conditions had turned WHAT?" John Calhoun poses with his rodents inside the mouse utopia.Yoichi R Okamoto, Public Domain

John Calhoun poses with his rodents inside the mouse utopia.Yoichi R Okamoto, Public Domain Alpha male mice, anyone?

Photo by

Alpha male mice, anyone?

Photo by