When talking with other parents I know, it's hard not to sound like a grumpy old man when we get around to discussing school schedules. "Am I the only one who feels like kids have so many days off? I never got that many days off when I was a kid! And I had to go work in the coal mine after, too!" I know what I sound like, but I just can't help it.

In Georgia, where I live, we have a shorter summer break than some other parts of the country. But my kids have the entire week of Thanksgiving off, a week in September, two whole weeks at Christmas, a whole week off in February, and a weeklong spring break. They have asynchronous days (during which they complete assignments at home, which usually takes about 30 minutes) about once a month, and they have two or three half-day weeks throughout the year. Quite honestly, it feels like they're never in school for very long before they get another break, which makes it tough to get in a rhythm with work and career goals. Plus, we're constantly arranging day camps and other childcare options for all the time off. Actually, I just looked it up and I'm not losing my mind: American kids have fewer school days than most other major countries.

So it caught my attention in a major way when I read that Whitney Independent School District in Texas recently decided to enact a 4-day week heading into the 2025 school year. That makes it one of dozens of school districts in Texas to make the change and over 900 nationally.

Giphy

Giphy

The thought of having the kids home from school EVERY Friday or Monday makes me want to break out in stress hives. But this 4-day school week movement isn't designed to give parents a headache. It's meant to lure teachers back to work.

Yes, teachers are leaving the profession in droves and young graduates don't seem eager to replace them. Why? The pay is bad, for starters, but that's just the beginning. Teachers are burnt out, undermined and criticized relentlessly, held hostage by standardized testing, and more. It can be a grueling, demoralizing, and thankless job. The love and passion they have for shaping the youth of tomorrow can only take you so far when you feel like you're constantly getting the short end of the stick.

School districts want to pay their teachers more, in theory, but their hands are often tied. So they're getting creative to recruit the next generation of teachers into their schools — starting with an extra day off for planning, catch-up, or family time every week.

Teachers in 4-day districts often love the new schedule. Kids love it (obviously). It's the parents who, as a whole, aren't super thrilled.

Photo by National Cancer Institute on Unsplash

Photo by National Cancer Institute on Unsplash

So far, the data shows that the truncated schedule perk is working. In these districts, job applications for teachers are up, retirements are down, and teachers are reporting better mental well-being. That's great news!

But these positive developments may be coming at the price of the working parents in the communities. Most early adopters of the 4-day week have been rural communities with a high prevalence of stay-at-home parents. As the idea starts to take hold in other parts of the country, it's getting more pushback. Discussions on Reddit, Facebook, and other social media are overrun with debate on how this is all going to shake up. Some parents, to be fair, like the idea! If they stay-at-home or have a lot of flexibility, they see it as an opportunity for more family time. But many are feeling anxious. Here's what's got those parents worried:

The effect on students' achievement is still unclear.

The execution of the 4-day week varies from district to district. Some schools extend the length of each of the four days, making the total instructional time the same. That makes for a really long day, and some teachers say the students are tired and more unruly by the late afternoon. Some districts are just going with less instruction time overall, which has parents concerned that their kids might fall behind.

4-day school weeks put parents in a childcare bind.

Having two working parents is becoming more common and necessary with the high cost of living. I know, I know — "school isn't daycare!" But it is the safe, reliable, and educational place we send our kids while we need to work.

Families with money and resources may be able to enroll their kids in more academics, extracurriculars, sports, or childcare, but a lot of normal families won't be able to afford that cost. Some schools running a 4-day week offer a paid childcare option for the day off, but that's an added expense and for families with multiple kids in the school system, it's just not possible.

This will inevitably end with some kids getting way more screentime.

With most parents still working 5-day weeks, and the cost of extra activities or childcare too high, a lot of kids are going to end up sitting around on the couch with their iPad on those days off. I'm no expert, and I'm certainly not against screentime, but adding another several hours of it to a child's week seems less than ideal.

Of course there are other options other than paid childcare and iPads. There are play dates, there's getting help from family and friends. All of these options are an enormous amount of work to arrange for parents who are already at capacity.

Working 4 days is definitely a win for teachers that makes the job more appealing. But it doesn't address the systemic issues that are driving them to quit, retire early, or give up their dreams of teaching all together.

Giphy

Giphy

A Commissioner of Education from Missouri calls truncated schedules a "band-aid solution with diminishing returns." Having an extra planning day won't stop teachers from getting scapegoated by politicians or held to impossible curriculum standards, it won't keep them from having to buy their own supplies or deal with ever-worsening student behavior.

Some teachers and other experts have suggested having a modified 5-day school week, where one of the days gets set aside as a teacher planning day while students are still on-site participating in clubs, music, art — you know, all the stuff that's been getting cut in recent years. Something like that could work in some places.

As a dad, I don't mind the idea of my busy kids having an extra day off to unwind, pursue hobbies, see friends, catch up on projects, or spend time as a family. And I'm also very much in favor of anything that takes pressure off of overworked teachers. But until we adopt a 4-day work week as the standard, the 4-day school week is always going to feel a little out of place.

This article originally appeared in February

Courtesy of Kerry Hyde

Courtesy of Kerry Hyde Courtesy of Kerry Hyde

Courtesy of Kerry Hyde Courtesy of Kerry Hyde

Courtesy of Kerry Hyde Courtesy of Kerry Hyde

Courtesy of Kerry Hyde A heart shaped neon sign in the dark

Photo by

A heart shaped neon sign in the dark

Photo by

Photo by

Photo by

The paint companies are dying to know the secret formula for the new color.

The paint companies are dying to know the secret formula for the new color. A close-up of the human eye.

A close-up of the human eye.  Lady Liberty welcomes people to New York.

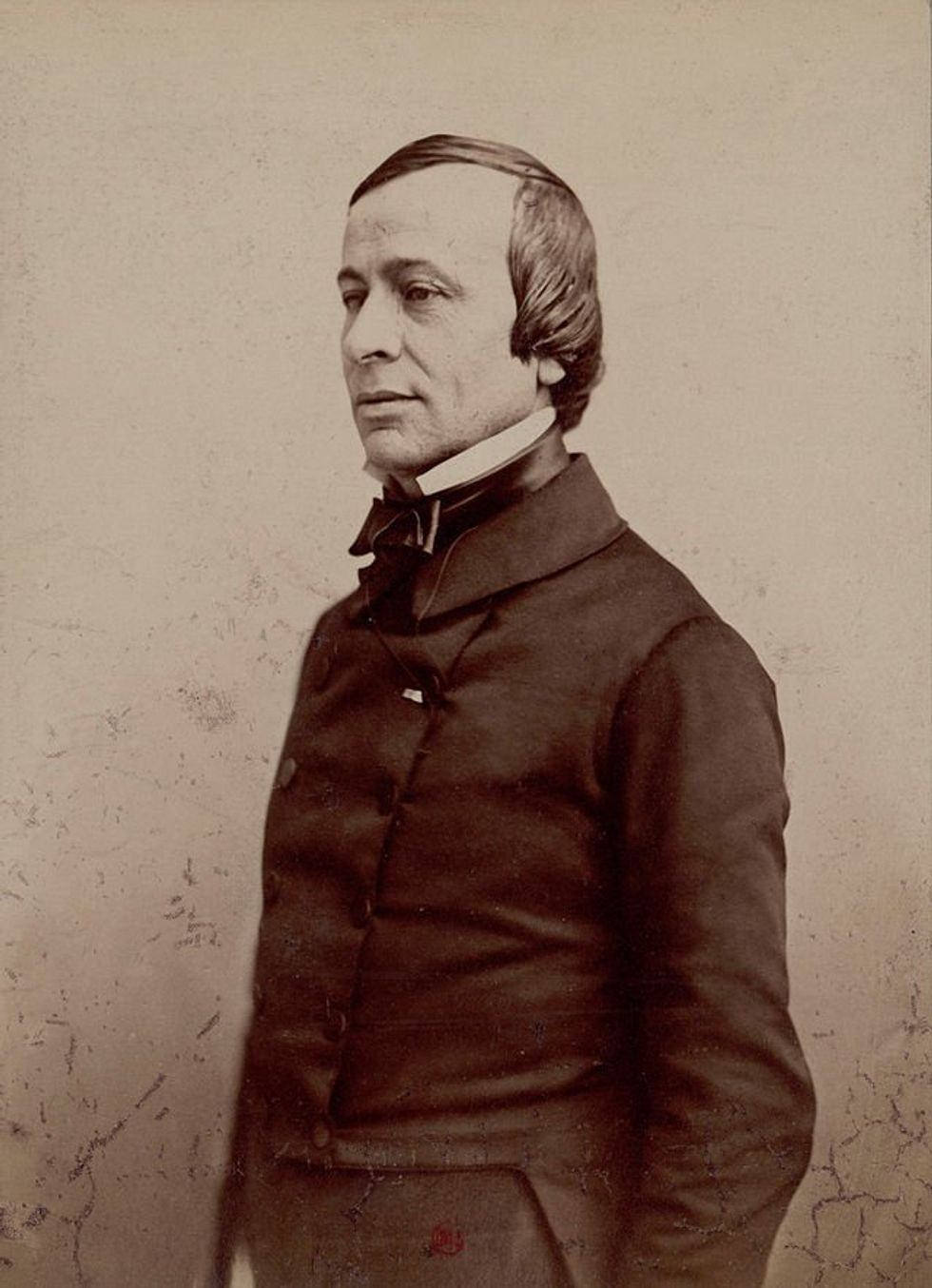

Lady Liberty welcomes people to New York. French abolitionist Édouard René de Laboulaye, who commissioned the Statue of Liberty.

French abolitionist Édouard René de Laboulaye, who commissioned the Statue of Liberty.