High schoolers preserved a Japanese internment camp for decades. Now, it’s a national park.

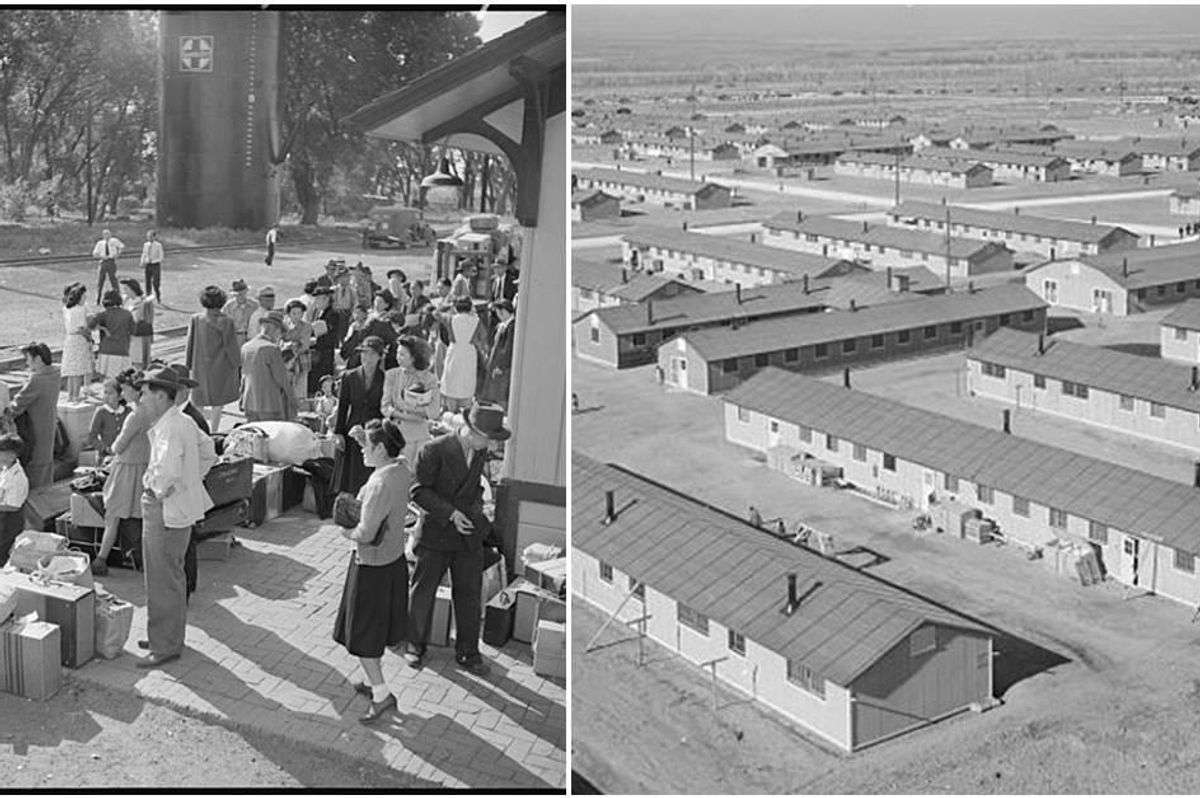

The Amache Internment Camp near Granada, Colorado.

After the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor in 1941, a wave of fear ran through the country that led America to violate the civil liberties of tens of thousands of its own citizens. In 1942, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which led to the internment of 120,000 Japanese Americans and people of Japanese ancestry in ten camps throughout the country.

Two-thirds of those interned were U.S. citizens.

The smallest of the camps, Amache in southeast Colorado, housed around 10,000 internees from 1942 to 1945, with a peak of 7,318 in 1943.

At the camp, internees lived in military-style barracks. Some worked producing agricultural products and others labored in the silkscreen shop or at the cooperative store. The camp also had a barbershop, schools for children and a hospital. Amache also had the largest number of internees volunteer or be drafted into service during World War II of any internment camp.

After the war, in 1947, most of Amache’s original building stock was sold through the War Assets Administration.

Registering the first arrivals at the Amache Internment Camp.

The Japanese internment was one of America’s most shameful acts of cowardice and bigotry. In 1988, President Ronald Reagan formally apologized for the atrocity calling it a “grave wrong” and used the moment to reaffirm “our commitment as a nation to equal justice under the law.”

John Hopper was a new social studies teacher at Granada High School in Colorado when he first visited the plot of land where the Amache Internment Camp once stood. “It just looked like a sagebrush cactus hill with cattle on it,” he told the Christian Science Monitor.

Three years later, some of Hopper’s “really bright and willing students” wanted to interview a camp survivor, which led him to create a nonprofit, the Amache Preservation Society (APS). The extracurricular activities surrounding Amache and its history soon evolved into a class at Granada.

I\u2019m incredibly grateful for Granada High School Principal John Hopper and his students who have worked to preserve Amache and gave us a tour of the site today.\n\nAnd a huge thanks to Granada for their willingness to donate their land.pic.twitter.com/S1t1DkwcU7— Michael Bennet (@Michael Bennet) 1645315272

Over the years, students enrolled in the class have worked on the preservation of the site by tending to the cemetery or other landmarks. They have helped to work at the Amache Museum as docents or on the site as tour guides.

“The first time I ever saw John’s kids give a presentation, ... I thought, OK, this is what this is all about,” Bonnie Clark, an anthropology professor at the University of Denver and leader of the DU Amache Project, told Christian Science Monitor. “They are super engaged.”

Over the years, thanks in part to work done by the students, Amache has been a place for camp survivors and their descendants to visit and pay homage to loved ones while keeping the memory of the tragedy alive.

View of Granada War Relocation Center from the interpretive signs at the entrance.

For the students, caring for Amache and its history has been a lesson in compassion.

“It’s taught me a lot about empathy,” Bailey Hernandez, a junior, said. “You start to think, well, how would I have reacted if my family was forced into one of these camps?”

For Hopper, now the dean of students at Granada School District RE-1, it’s an opportunity to teach students about individual rights in a very real way.

“It is a heavy, heavy topic, especially when you talk about civil liberties,” he said. “But that’s part of my job I enjoy talking about–needs to be talked about.”

In 2006, Amache was designated as a national historic landmark, and last month, President Joe Biden made it part of the National Park Service. But in a way, it was already being treated that way by the students of Granada and Hopper.

The Japanese internment during World War II was a catastrophic lapse in judgment by the American people and its leaders that should never happen again. The best way to ensure that is by remembering our past and never forgetting its lessons. Hopper and his students’ incredible work has kept those priceless memories alive for future generations, thus helping to protect all of us from injustice.

- The moving reason these Japanese-American basketball leagues ... ›

- A mini history lesson about the concentration camps on American ... ›

- 21 powerful photos show what life inside a Japanese internment ... ›

- Eagle Scout raises $77,000 for veterans' memorial - Upworthy ›

- Traveling couple reveals which national park is the best - Upworthy ›

Rihanna Nails GIF

Rihanna Nails GIF

Good luck trying to catch a gazelle.

Good luck trying to catch a gazelle. Chickens will eat just about anything.

Chickens will eat just about anything. There's actually a big difference between horses and zebras besides just the stripes.

There's actually a big difference between horses and zebras besides just the stripes. Stop Right There The End GIF by Freeform

Stop Right There The End GIF by Freeform