Imagine your childhood neighborhood. Now imagine waking up one morning to a bulldozer ready to plow it down.

Plenty of people would, understandably, have an emotional reaction at the idea that the place they grew up was about to be torn to the ground.

For some, a city full of little boutiques and expensive coffee shops is the ultimate sign of progress and growth. But for the people who have lived there much longer — whose homes stood long before the frozen yogurt and the bike lanes — this can be a painful process.

As the face of their neighborhood transforms, the cost of living is driven up, often causing longtime residents to lose their homes and, along with it, their connection to a place and its history.

But does revitalizing a neighborhood have to mean erasing its history? In the Westside neighborhood of Covington, Kentucky, the answer is a resounding “no.”

Photo by Annie O'Neill, provided by the Center for Great Neighborhoods of Covington.

Covington once looked like any other casualty of urban flight, as residents began to move from the city to the suburbs for a variety of reasons. Then a state highway was expanded a decade ago, splitting the city’s Westside neighborhood right down the middle. This contributed to disinvestment in the area, as historic buildings fell into disrepair and the value of homes began to fall. Before long, Covington was a city in decline.

But instead of getting discouraged, community members and organizations began to mobilize to save their city.

One organization in particular — the Center for Great Neighborhoods of Covington — had a vision for change. And unlike many revitalization efforts elsewhere, they didn’t want Covington to become unrecognizable. In fact, they wanted the exact opposite.

Photo by Annie O'Neill, provided by the Center for Great Neighborhoods of Covington.

Rather than treating Covington like a blank slate for outsiders to change, they turned to the existing community to reclaim the city they loved.

They tried something called “creative placemaking,” which encourages creative and artistic efforts to strengthen a community from within. And they did this by getting their own local artists involved.

Photo by Annie O'Neill.

Kate Greene, program manager of community development at the Center, says that Covington had everything it needed all along. “It has a makers’ history,” she explains. “[There’s] a ton of artists — whether they define themselves as artists or not.”

The Westside had an abundance of creativity — be it storytelling, sculpture, ceramics, or stained glass — just waiting to be tapped into. “We’re really trying to take that and bring it to the surface again,” Greene explains.

Photo by Annie O'Neill.

For example, the Center worked with a local artist to organize a community dinner that included a stenciled paper tablecloth that attendees could write on. Residents were asked about their neighborhoods and how to make them better — focusing on access to fresh food in particular — and they responded directly on the tablecloth.

In this way, the Center was able to reach residents who might otherwise not share. “[It was] to get other people’s voices … who maybe weren’t inclined to raise their hand or speak up,” says Greene.

Photo by Stacey Wegley, provided by the Center for Great Neighborhoods of Covington.

It was these voices, many of whom were engaged for the first time, that began to transform Covington.

With the help of grants — including from The Kresge Foundation, as part of their Fresh, Local and Equitable initiative known as FreshLo — the Center was able to empower residents.

These funds allowed them to teach classes, rehab historic homes, organize community events, create artists’ studios, and most importantly, build lasting connections, with a particular focus on the Westside neighborhood.

“A lot of people [think] it’s just murals and sculptures and mosaics … but in our work, that’s really not important to us,” Greene explains. “How did you build that sculpture together? What connections were made? Who was making decisions? Did new leaders surface? All of those elements are the key.”

Tatiana Hernandez, Senior Program Officer at the Kresge Foundation, agrees. "Creative approaches are needed to meaningfully address the systemic barriers facing low-income residents," she explains. "[We can] give residents a sense of agency, and contribute to the narrative of a place."

Photo by Stacey Wegley.

“[It’s] a way to build pride in the community,” Greene adds.

These efforts have allowed the neighborhood to hold onto its identity and history, even as the city changes.

That identity is what makes Covington unique.

“I don't [want] Covington to lose its identity and become gentrified,” says Tashia Harris, a lifetime resident and community consultant for the Center. “I like the beautiful mix of cultures that I'm surrounded by here, and creative placemaking [is] helping Covington keep its identity.”

Photo by Stacey Wegley.

Your childhood neighborhood might not have had a gourmet sandwich shop. But maybe it had a corner store stocked with your favorite soda or an old Victorian house on the corner that always reminded you of a castle. Maybe it had a barber that cut your hair for the first time or a rec center where you learned to swim.

Revitalizing a city doesn’t have to mean losing what makes it special. And in Covington, Kentucky, it’s places just like these — and the history they hold — that make it still feel like home.

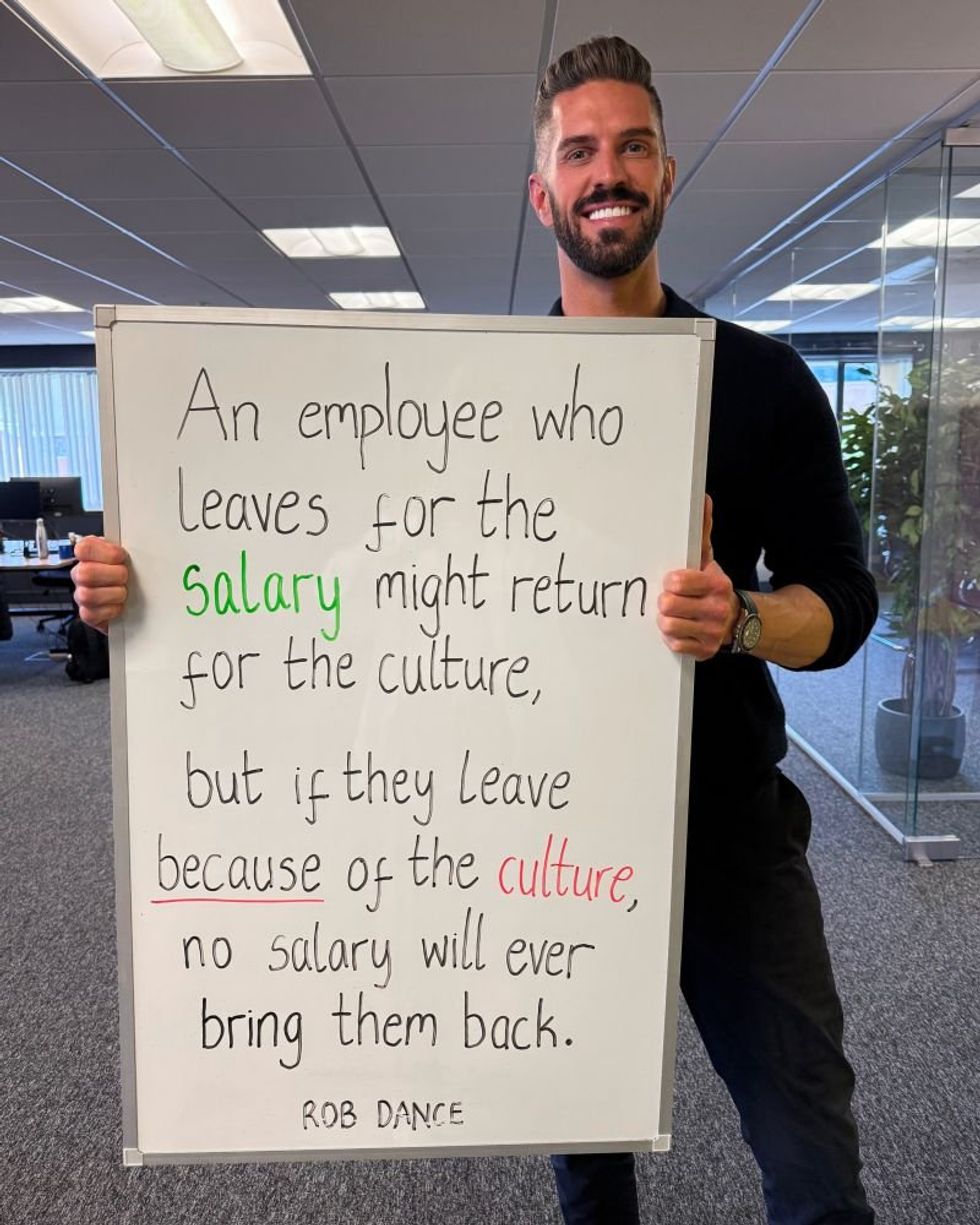

CEO Rob Dance holds up a whipe board with his culture philosophy.

CEO Rob Dance holds up a whipe board with his culture philosophy.  A heart shaped neon sign in the dark

Photo by

A heart shaped neon sign in the dark

Photo by