George Washington told America that political parties were our 'worst enemy.' He was right.

President George Washington warned Americans of the dangers of partisanship in his 1796 farewell address — and he didn't mince words.

The entire address is worth a read, but Washington's descriptions of "the Spirit of Party," which he said "is seen in its greatest rankness" in freely elected democracies and "is truly their worst enemy," are particularly intriguing.

Check out a bit of what he said about partisanship:

It serves always to distract the Public Councils and enfeeble the Public administration. It agitates the community with ill-founded jealousies and false alarms, kindles the animosity of one part against another, foments occasionally riot and insurrection. It opens the door to foreign influence and corruption, which finds a facilitated access to the government itself through the channels of party passions. Thus the policy and the will of one country are subjected to the policy and will of another.

Umm, prophetic much?

Of course, when Washington wrote those words, the parties we now see dominating American politics didn't exist. The "Spirit of Party" was burgeoning, however, and it doesn't take a political genius to see that the partisan divide we're currently experiencing was an inevitable outcome of such a spirit.

After all, partisan politics is divisive in its very nature. This is especially true in our two-party system, where supposedly opposite forces compete in a constant tug-of-war for power. In the abstract, that may seem like some form of balance, but in actuality, it's a recipe for deadlock and potential disaster:

There is an opinion that parties in free countries are useful checks upon the administration of the government and serve to keep alive the spirit of liberty. This within certain limits is probably true; and in governments of a monarchical cast, patriotism may look with indulgence, if not with favor, upon the spirit of party. But in those of the popular character, in governments purely elective, it is a spirit not to be encouraged . . . there being constant danger of excess, the effort ought to be by force of public opinion, to mitigate and assuage it. A fire not to be quenched, it demands a uniform vigilance to prevent its bursting into a flame, lest, instead of warming, it should consume.

Perhaps that's why the largest American voting block identifies as Independent.

I count myself among the 42% of U.S. voters who don't align themselves with a political party. Raised in a definitively non-partisan household, I've never felt any desire to call myself Democrat or Republican, Libertarian or Green, or any other party affiliation. In addition, I avoid arguments that center partisanship, and quickly grow weary of the childish, name-calling bickering that too often takes places between people who see themselves as mortal enemies based on red vs. blue.

However, I still get labeled with a political party almost every time I share an opinion on an issue—especially online—despite never stating any party preference. It's virtually impossible to discuss any political or social issue these days without someone assigning you to a party, and then assuming you support the party's platform and ideology whole cloth.

Our brains naturally categorize things, and the prevalence of partisanship leads people to automatically sort individuals into one of two distinct camps. Far too many people don't seem to grasp that it's possible to engage in social and political discourse without being entrenched in "the spirit of party."

People's beliefs and views don't fall neatly into two categories, so let's stop behaving as if they do.

When we step back and think about the depth and diversity of human thought, it's immediately clear that each of us has a unique combination of beliefs and experiences. That makes sorting millions of Americans into two political categories absurd.

And yet, that's what people do all the time when they assign labels like liberal/conservative, Democrat/Republican, blue/red, and left/right to people based on one expressed opinion. They do it without thinking. They do it without investigating. And they do it with deeply ingrained prejudices and assumptions that are not only unfair, but dangerous, as they lead to factionalism and blind loyalty.

Many people decry blind loyalty to party, but don't recognize it in themselves.

The view from top of the political fence is interesting. From what I can see, the problem with partisan politics isn't the partisans who take it to the extreme; it's the nature of the beast itself. Each side demonizes the other so viciously that when one heads down the path of partisan thinking, aligning with one side seems the only truly virtuous thing to do.

If your first response to that statement is, "But the [fill in opposing party] truly IS evil! Someone has to stop them!" take a step back. Folks on the other side are saying exactly the same thing about you, and they believe it just as strongly, for reasons they feel are just as legitimate. That kind of us vs. them thinking can easily lead to a righteous sense of party loyalty, which can easily lead to putting party before country.

Washington saw this coming when he expressed concern that political parties could result in loyalty to one's party overriding one's loyalty to the nation and to the common good. He also pointed out the corruptive influence they can have:

The alternate domination of one faction over another, sharpened by the spirit of revenge, natural to party dissension, which in different ages and countries has perpetrated the most horrid enormities, is itself a frightful despotism. But this leads at length to a more formal and permanent despotism. The disorders and miseries which result gradually incline the minds of men to seek security and repose in the absolute power of an individual; and sooner or later the chief of some prevailing faction, more able or more fortunate than his competitors, turns this disposition to the purposes of his own elevation, on the ruins of public liberty.

Without looking forward to an extremity of this kind (which nevertheless ought not to be entirely out of sight), the common and continual mischiefs of the spirit of party are sufficient to make it the interest and duty of a wise people to discourage and restrain it.

We would be wise to heed Washington's warnings, on an individual level if not on a national one. Obviously, America's two-party system isn't going anywhere anytime soon, but it's only fueled by our participation. Let's discuss the issues, but ditch the partisanship. If we continue to cling to divisive modes of governing, we'll never find the unity we so desperately need.

Dexters Laboratory What A Fine Day For Science GIF

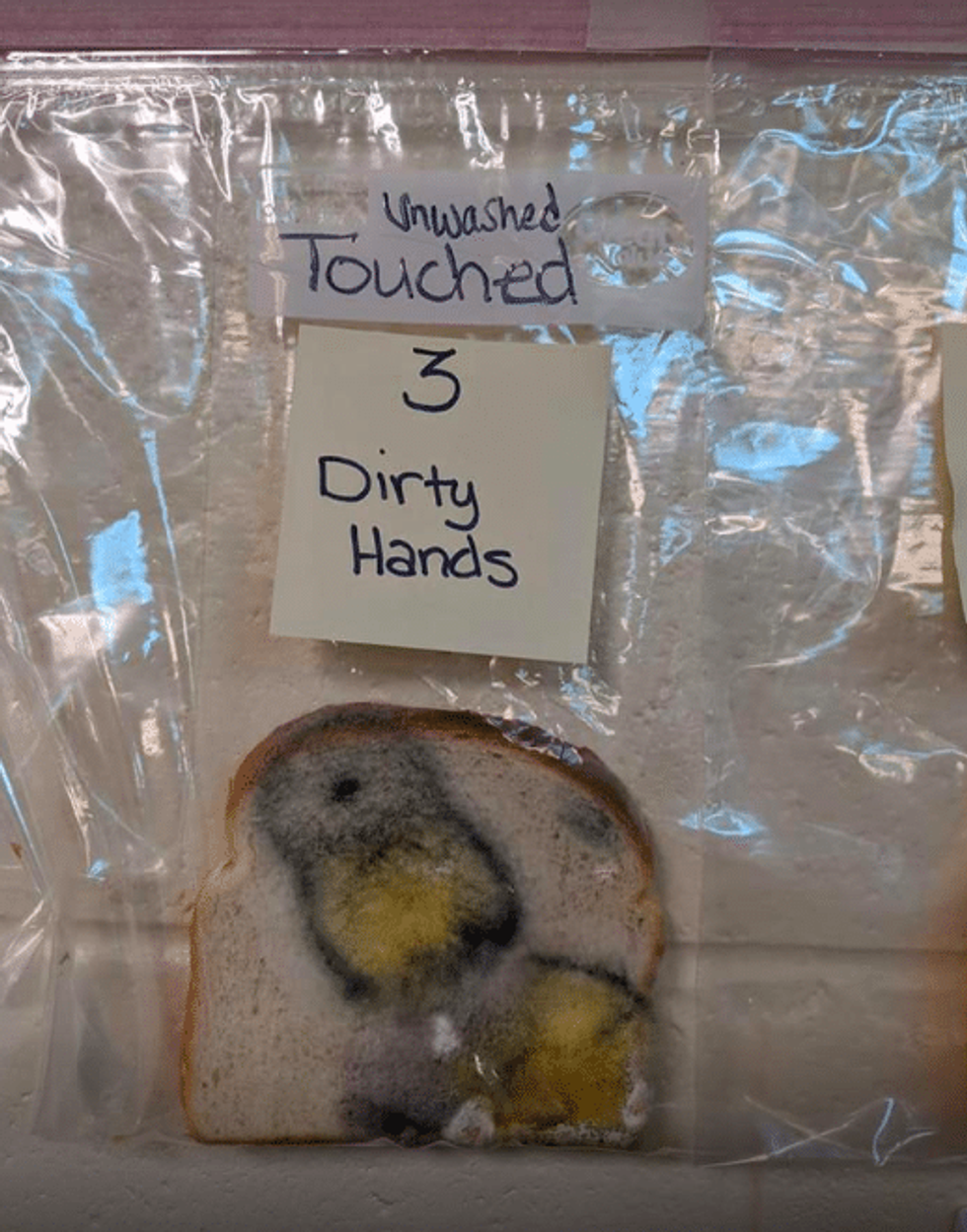

Dexters Laboratory What A Fine Day For Science GIF The bread doesn't lie. Facebook/Jaralee Metcalf

The bread doesn't lie. Facebook/Jaralee Metcalf

luxo jr lamp GIF by Disney Pixar

luxo jr lamp GIF by Disney Pixar Plastic doesn't belong in the ocean.

Plastic doesn't belong in the ocean. A father does his daughter's hair

A father does his daughter's hair A father plays chess with his daughter

A father plays chess with his daughter A dad hula hoops with his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad hula hoops with his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. A dad talks to his daughter while working at his deskAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad talks to his daughter while working at his deskAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. A dad performs a puppet show for his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad performs a puppet show for his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. A dad walks with his daughter on his backAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad walks with his daughter on his backAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. a dad carries a suitcase that his daughter holds onto

a dad carries a suitcase that his daughter holds onto A dad holds his sleeping daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad holds his sleeping daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. A superhero dad looks over his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A superhero dad looks over his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. A dad takes the small corner of the bed with his dauthterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad takes the small corner of the bed with his dauthterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. Teaching in a racially and ethnically diverse world.

Teaching in a racially and ethnically diverse world.