From the top-down and the bottom-up, communities are coming together to end food deserts.

Take a moment to think about how far from your house you have to travel to buy fresh fruits, vegetables, or meat. If you have to travel at least one mile (or 10 miles in rural areas) to purchase fresh food, you, my friend, are living in a food desert.

A food desert looks less like this:

Photo by iStock.

And more like this:

Yes, there is access to food in a food desert. But not fresh produce or meat. Photo by iStock.

Food deserts tend to exist in low-income areas, where residents may not have access to reliable transportation, which makes traveling long distances difficult, time consuming, and expensive.

For example, in Baltimore, a heavily residential metropolitan area, 1 in 4 people live in a food desert.

According to the Baltimore Business Journal, Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake intends to introduce legislation offering, "new or renovating supermarkets in certain areas of the city an 80 percent discount on their personal property taxes for 10 years."

Those areas of the city are, of course, food deserts.

Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake. Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images.

And Rawlings-Blake is not alone. Between 2001 and 2011, 12 states, including Washington D.C., enacted healthier food legislation. Which is a good thing, because food deserts aren't just an isolated issue, they're a national problem.

An estimated 23.5 million people in the U.S. (that's 7% of the country) reside in a food desert.

Without access to groceries or supermarkets to buy healthy food, residents of these areas often resort to fast food or convenience stores, which can result in poor nutrition and an increase in diet-related diseases like heart disease and Type 2 diabetes.

Photo by iStock.

As part of First Lady Michelle Obama's Let's Move campaign, the current administration pledged to eliminate food deserts in America by 2017.

While many elected officials are doing what they can, the legislative process is often slow. Many people living in food deserts can't afford to wait until 2017 to get access to fresh food.

Grassroots organizations in cities and communities are helping chip away at the ambitious goal.

Consider the Real Food Farm, an urban farm in a Baltimore park. While Mayor Rawlings-Blake is proposing a bill to give tax cuts to supermarkets in food deserts in the near future, the volunteers from Real Food Farm are making sure the people in those areas have access to fresh produce right now.

Several times a week, volunteers harvest crops and drive to different communities to sell fresh produce from their truck, better known as a "mobile farmers market." They even match the first $5 customers spend. Thanks to the matching program, shoppers can take home a full bag of groceries for less than most meals at fast food restaurants.

Real Food Farm's mobile farmers market in action. Photo by Real Food Farm, used with permission.

Or consider Juices for Life, a fresh-pressed juice bar in the Bronx, which was opened by platinum-selling rap artists Styles P and Jadakiss with the goal of bringing healthier options to the community they love.

"If you walk down the block in the hood, it's nearly impossible to find something healthy to put in your body," Jadakiss said in a video for EliteDaily. "We didn't have the knowledge or the opportunity we do now. That's exactly what we're trying to give to our community."

Or consider the People's Community Market in West Oakland, California, where the community was so desperate for a grocery store but couldn't secure large private investors. Brahm Ahmadi, a local entrepreneur, took it upon himself to found the market and sell stock in the organization through a direct public offering, the same nontraditional approach used by Costco and Ben & Jerry's when they were up-and-coming businesses.

The individuals and families investing (each contributing a minimum of $1,000) have raised over $1 million to acquire a site and get to work building the much-needed grocery store.

West Oakland is one step closer to veggies on veggies on veggies. Photo by iStock.

All of these options are steps in the right direction toward solving a much bigger problem. They're a frequent reminder that when we come together, we can find meaningful solutions to challenging problems and help our communities thrive.

Some at-home perk simply can't be beat.

Some at-home perk simply can't be beat.  Mark (Adam Scott) at the infamous dance party scene in Severance.

Mark (Adam Scott) at the infamous dance party scene in Severance.  A

A  A man and woman chatting.via

A man and woman chatting.via  Coworkers having a conversation.via

Coworkers having a conversation.via  Coworkers having a conversation.via

Coworkers having a conversation.via  Rachel Ruff Cuyler explaining how she would "fix" Poolhouse' song to make it the next "Teenage Dirtbag." @rachelruffcuyler/

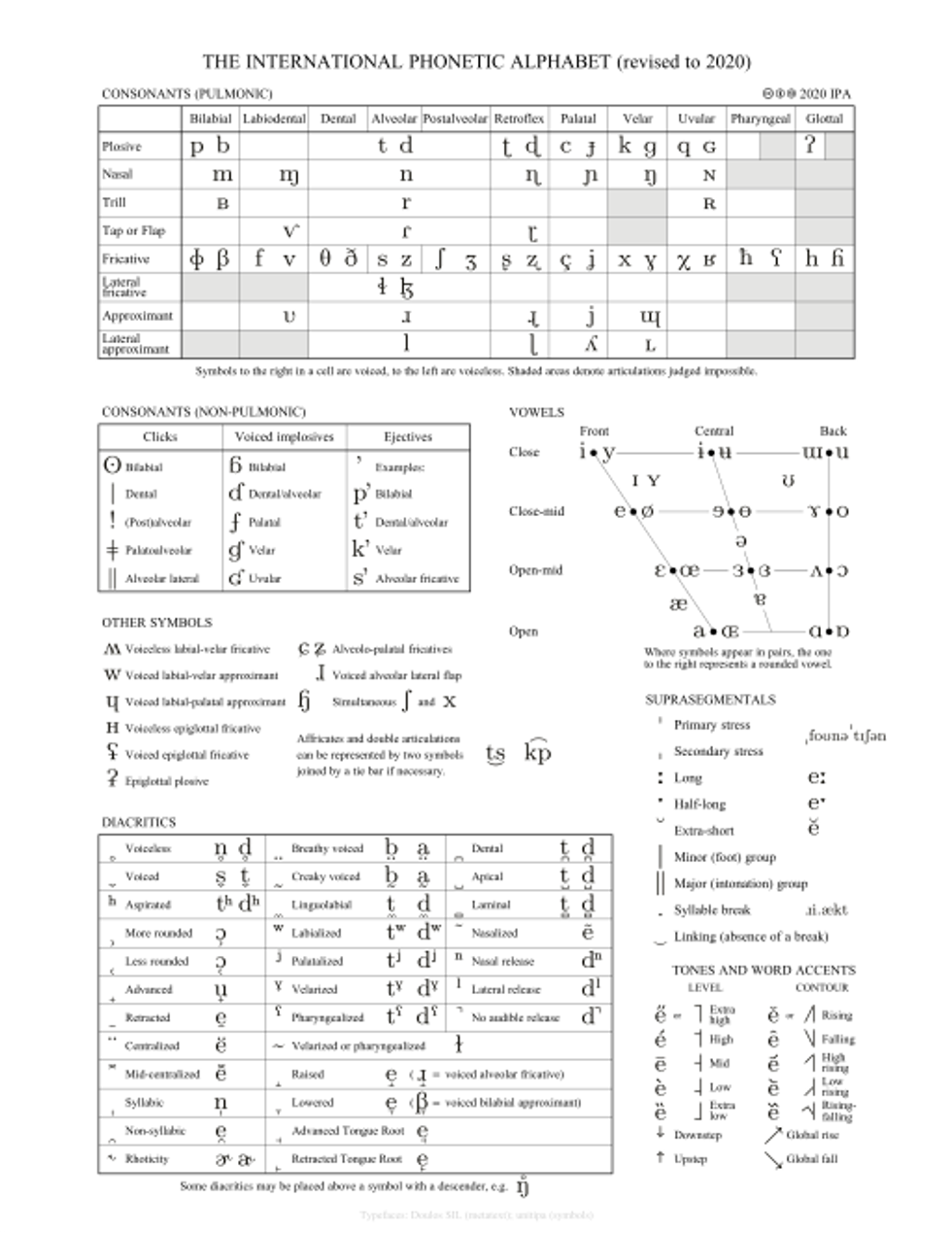

Rachel Ruff Cuyler explaining how she would "fix" Poolhouse' song to make it the next "Teenage Dirtbag." @rachelruffcuyler/ Not exactly a light read, but if you're serious about mastering your pronunciation the IPA can be a huge help.International Phonetic Association, CC BY-SA 3.0

Not exactly a light read, but if you're serious about mastering your pronunciation the IPA can be a huge help.International Phonetic Association, CC BY-SA 3.0