Former gang members are helping to end violence in L.A. through an awesome program.

Ex-gang members are taking their community back, one relationship at a time.

While growing up in Southwest Houston post-Rodney King, I heard a lot about the turbulence and gang violence taking place in South Central Los Angeles.

All images used with permission from "License to Operate."

Shows like "A Different World" and movies like John Singleton's "Boyz n the Hood" showcased the impact of gang violence and the unrest between communities of color and police.

This was the post-Jim Crow era, and black people were being pushed to the poorest corners of large cities, areas that funneled the worst drugs to a group of people already struggling to survive. With the rise of the cocaine epidemic, a push for economic improvement, and a desire for brotherhood, many young black men felt forced to join gangs.

I listened to my mostly black neighbors talk about making sure the young men in our community focused on school and work, rather than falling into what was seen as an unforgivable gang lifestyle.

But for people living in L.A., getting out of those lethal neighborhoods wasn't as easy as just going to class on time or getting an education. For the thousands of young black men who lost their lives to guns during the '80s and '90s, there were few ways out.

Aquil Basheer remembers feeling forced into gang life as a teenager.

"To get people out of the gang life, you have to show them that there's something more out there," said Basheer. "When I was coming up, that something more didn't exist."

Basheer was born in Pacoima, a neighborhood in Los Angeles. He got involved with gangs as a teenager, but a short stint in gangbanging led him to a life he eventually realized he didn't want. He narrowly escaped a prison sentence thanks to some influential role models, but he says many of his friends got life in prison or ended up buried.

For many, seeing a family member killed or losing a loved one too soon can change everything. For Basheer, it wasn't a single incident that changed everything, but rather a variety of experiences that came together to make a big issue clear to him: The city he loved was becoming unrecognizable.

Eventually, Basheer and other former gang members decided that enough was enough.

The city they knew and loved was now a breeding ground for terror. And it wasn't just their male friends who were in danger either. Now, mothers were dying — and grandmothers and children. Boundaries no longer existed, and Basheer knew that he and others had played a large role in developing that culture.

"We had to bring an [option] to the table that would get individuals away from their mindset that [this type of] life was the way to go," Basheer says.

Basheer noticed that lots of gang members wanted to change, particularly when they hit their 30s. As people matured, they wanted a safer city for their own children.

"When people start having children and when they see that their brothers and sisters are at risk, they reevaluate things and start wanting to make some major changes," Basheer said.

But to do so, they needed someone with street credibility to step in and act as a mentor.

The former gang members got together and developed a gang interventionist group.

The middle-aged men — once some of the most feared men walking the streets — decided that their children and their community deserved better. Instead of searching for help outside the community, the men looked inward to figure out how to instill peace and restoration to a city that needed it.

In 2006, the community organizers came together and developed what they called the Professional Community Intervention Training Institute (PCITI).

The plan was simple: First, they brought in a group of community elders. These men and women would act as an anchor to people in a community in crisis, such as mothers who lost sons and children who lost classmates.

By training these elders how to deal with trauma and assist in stopping gang violence, safety nets are created. Going into the community to get a larger grasp of the needs isn't as difficult as it was before.

"It's operational protocol," Basheer said. "You have to create a whole new nexus for them to attach themselves to, to get away from their normal of gang culture — the thought they have to be better than the next."

Then, most importantly, these community elders show volunteers and workers how to navigate a given neighborhood, how to mediate in stressful issues, and how to create real conflict resolution that works.

It’s this dedication to conflict resolution that is sparking a rebirth in the city’s most plagued communities.

According to the organization, PCITI has a 93% success rate, meaning that many who were caught up in gang life are now actively working toward other options.

On a human level, PCITI has managed to grow relationships with young people in the community, which is where the real change is starting to happen. Finding at-risk gang members isn't exactly difficult, Basheer says, because most don't hide their affiliation — instead, they brag about it.

And rather than making exiting a gang the main goal, Basheer's team works to show gang members there are other options, a concept that hasn't necessarily been taught to many living in impoverished areas.

To understand how drastic this improvement is, you have to know a bit about L.A.'s gang history.

Los Angeles has long been hailed as the "gang capital" of America. Currently, there are believed to be 450 active gangs in the city — many of which have existed for over 50 years. Collectively, it's estimated that 45,000 individuals have been members. During the late '80s to the early '90s, almost 1,000 people died due to homicide in Los Angeles every year.

It's no secret that black and Latino men were — and still are — particularly susceptible to gang violence. In 1996, 46% of all gang members identified as Hispanic or Latino, and 35% were black. And 79% of large cities reported gang problems from 2008 to 2012.

While Basheer’s program is certainly a pleasant addition to the city, it’s just one piece to a very complicated puzzle that continues to take lives.

Even though gang violence was steadily declining during the early 2000s, L.A. recently saw its highest rise in gang violence since 2009. LAPD data showed that almost 60% of homicides were gang-related, putting a damper on an already struggling city.

But that’s exactly why Basheer and others keep going: They know that the road to peace and stability is never smooth. Instead, it’s often turbulent and complicated.

“These are everyday people that are part of the solution,” said Basheer. “They aren’t necessarily police officers or firemen. They’re citizens that want to improve lives in their communities.”

Basheer has also taken this plan to various communities in South Africa and Europe.

Most recently, he spoke at a UN conference focused on bringing safety to some of the world's largest cities.

"Surprisingly, the international communities get it and are way more on task than [American] urban cities," Basheer said.

He's also gotten involved with the Black Lives Matter movement, and he says this is what shows him the plan has strong potential; if his program works, the template has to be able to be replicated in other besieged areas too.

Community policing is important and effective — and it could be one of our best ways forward.

After documenting Basheer's movement in the documentary "License to Operate," producer Mike Wallen says he was surprised by how well this system was working.

“I felt like I was from an open-thinking, progressive family, but you don’t know what you don’t know,” said Wallen, who grew up in L.A. After taking on the film production pro bono, he got heavily involved with the interventionists and says he listened more than he spoke.

“It’s really important that we all care about this, whether we’re directly affected or not," Wallen said.

As distrust continues between communities of color and police, Wallen is right: Programs like this are key. It's important for people to see familiar faces in positions of authority. Engaging both parties to create solutions is a tool that everyone can work toward sharpening.

"The goal is to create sustainable communities, which are violence free, that can create their own version of sustainability," Basheer said.

The bottom line is that gang violence is a complicated issue.

But the best way to combat it might be the most basic and the most emotional: reaching out to others in your community to promote human connection, support, and mentorship.

Many young people join gangs because of the respect that comes with it and the sense of community they find. And, certainly, one solution will not fix a decades-long problem. With more people like Basheer in the mix, it is definitely possible to create a culture in which gang violence becomes a thing of the past.

Corgi cuddles spreading joy and smiles!

Corgi cuddles spreading joy and smiles! Joyful moments with furry friends! 🐶❤️

Joyful moments with furry friends! 🐶❤️

Cat sitting in a woman's lap

Cat sitting in a woman's lap Cat making biscuits

Cat making biscuits Who knew yawning and stretching could be a sign of love?

Who knew yawning and stretching could be a sign of love?

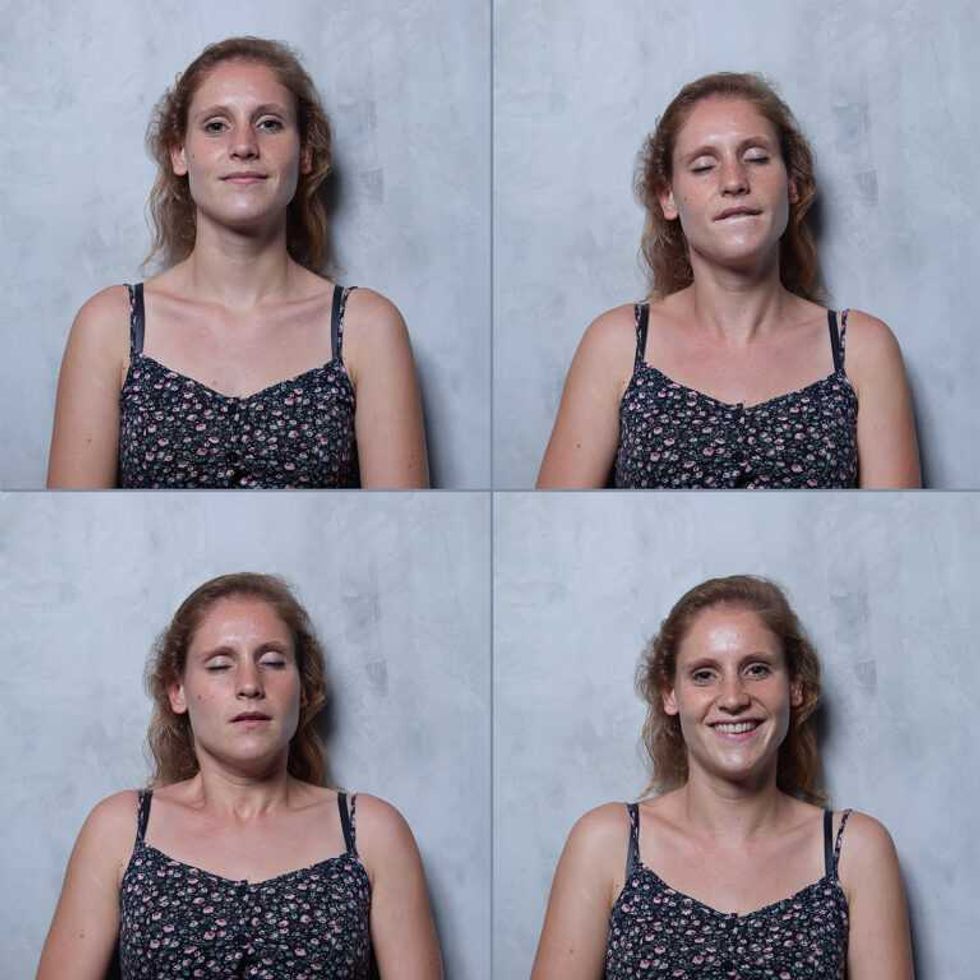

An O Project participant.

An O Project participant.  An O Project participant.

An O Project participant.  An O Project participant.

An O Project participant.  An O Project participant.

An O Project participant.  An O Project participant.

An O Project participant.  An O Project participant.

An O Project participant.  An O Project participant.

An O Project participant.  An O Project participant.

An O Project participant.  An O Project participant.

An O Project participant.  An O Project participant.

An O Project participant.