We need a system for keeping conspiracy kooks out of office. Here's what that might entail.

One of the greatest things about the American experiment is the idea of self-rule, "a government of the people, by the people, for the people." Instead of power being held by a ruling class or monarchical dynasty, we routinely elect our leaders from among the citizenry to represent us in the government.

It's a system that works well when the representatives we choose are among the best of us. But the fact that virtually anyone can serve as an elected official also leaves us open to potentially disastrous leadership. We could end up with, say, a malignant narcissist autocrat wannabe or a kooky conspiracy theorist in positions of power—a reality that clearly puts the security of the entire country in danger.

The Constitution stipulates the requirements for holding office, and they are extremely simple by design. To serve in Congress, you have to be 25 years old, a citizen for at least seven years, and live in the area you represent. To serve as President, you have to be 35 years old, a natural-born citizen of the U.S. and have lived in the country for 14 years.

That's it. Super basic. On paper, a guy who collects trash for a living (a noble job—no criticism) is as qualified to be president or a member of Congress as a professor of constitutional law. There are no educational qualifications and no previous job or relevant experience required. There are also no psychological screenings, meaning that, theoretically, a literal psychopath serial killer could be elected to the position that controls the nuclear codes.

A viral video shared by "Politics Girl" highlights how absurdly weird it is that people can get a job in the most powerful positions in our government without being the least bit qualified:

It's true. There is no official vetting process. And while there are some constitutional disqualifications—such as participating in rebellion or insurrection (ahem), impeachment when included as part of a conviction (double ahem), and not taking the oath of office—most attempts to create additional qualifications have been deemed unconstitutional.

There's wisdom in that. Adding official qualifications is a slippery slope, and most of what we could come up with would be arbitrary anyway.

Relevant job experience is a definite plus for a person seeking public service, no doubt. But one strength of our representative system is the diversity of experience and perspectives it inevitably brings to the table. Having lawmakers who come from a spectrum of careers and backgrounds is a good thing, and can help ensure that more Americans are seen and heard in our government.

What about education? Most of us would agree that an elected official should be smart and knowledgeable. But how do we measure that? Quality of education can vary greatly, rendering specific levels of education virtually meaningless. Earning a degree might indicate an ability and willingness to learn and work, but it is not a guarantee of intelligence or relevant knowledge. People who haven't gone to college might have gained skills and insights through service to their community that would be more valuable to governance than book learning. And since there are barriers that make higher education inaccessible for some Americans, having an education requirement would be an unjust form of gatekeeping.

They have to at least know about government, though, right? A certain understanding of civics seems like a logical prerequisite, but how do we measure that? Do we create a test a person has to pass before they can get on a ballot? Might not be a bad idea, but would that actually solve the real problem we're looking at? A constitutional law degree doesn't make someone conscientious, and a genocidal maniac could study and pass a civics test.

So how about a psychological screening of some sort? Again, not a bad idea on the surface, but here we run into the issue of who conducts it and what they should look for. Would there actually be a set of dealbreaker diagnoses that would disqualify someone? Or would we just provide the results to the public and let them decide themselves whether a person is fit to serve?

The problem there, of course, is that mental health issues that shouldn't preclude someone from serving—an anxiety disorder, for example—could unfairly lead people away from a candidate due to the stigma attached to mental health. There's a huge difference between a run-of-the-mill mental health issue and a full-blown dangerous personality disorder, but any diagnosis could be weaponized. Where and how do we draw the line?

Since party politics is a feature of our system (one that George Washington warned us against, for good reason), some make the argument that the parties themselves need to vet candidates before they get on the primary ballots. A Brookings Institute report from 2018 pointed out that activist groups have begun producing more candidates, which is leading to more underqualified, ideologically extremist candidates. If we're going to have a two-party system, those two parties need to ensure that the candidates in their parties aren't total whack jobs. The suggestion made by the report authors is "to strengthen the position of the institutional parties so that they maintain voice and influence in the process of developing candidacies—not instead of voters and activists, but alongside them."

But what happens if a party itself moves farther to the extremes, either because of the candidates that are getting attention or because the social reality has pushed the voters in that direction? (Ahem, QAnon.)

And isn't partisan politics itself a big reason we're in this spot? A system that places people in two distinct boxes is inevitably going to lead to extremism, as parties resort to increasing demonization of the other side as they vie for power and influence.

Lee Drutman, senior fellow at the New America think tank, wrote about why we need multiple parties in the U.S. in 2019:

"Under the two-party system, U.S. politics are stuck in a deep partisan divide, with no clear winner and only zero-sum escalation ahead. Both sides see themselves as the true majority. Republicans hold up maps of the country showing a sea of red and declare America a conservative country. Democrats win the popular vote (because most Americans live in and around a handful of densely populated cities) and declare America a progressive country.

The only way to break this destructive stalemate is to break the electoral and party system that sustains and reinforces it. The United States is divided into red and blue not because Americans want only two choices. In poll after poll, majorities want more than two political parties."

Expanding our options beyond Republican and Democrat sounds like a fabulous idea in my book.

In the meantime, we the people are still left to vet the people who get put on the ballot. So maybe the answer in the short term is to 1) Encourage and enable better candidates to run for office, and 2) Educate and encourage the voting populace to do a better job of vetting. Relying on a candidate's own messaging isn't enough. What have they actually done in their communities? What have they said in public or on social media? Look at various media sources to see what kinds of red flags may have been spotted.

Of course, this process only works if people actually care about not having kooky conspiracy theorists and malignant narcissist authoritarians in our government. Ultimately, when we start electing highly problematic people to lead us, that's a reflection of where we are as a society. And unfortunately, there's no quick fix for a voting populace that doesn't recognize when an elected official is an actual danger to the country and when they're just being subject to partisan attacks. (A good hint to the former is when members of the official's own party, especially one that tends to stick together, speak out and say, "Yeah, this is a bridge too far.")

Answers here aren't obvious or simple, but it's clear we need to do something different. The way we're going now, we very well could end up with a psychopathic serial killer in Congress. And my biggest fear is that a good portion of the nation wouldn't even blink an eye if we did.

- Obama's post-election lunch with the former presidents is what ... ›

- The First Muslim and Native American women were just elected to ... ›

- The majority of women elected to Congress this year are former Girl ... ›

A woman reading a book.via

A woman reading a book.via A woman tending to her garden.via

A woman tending to her garden.via

Cats can be finicky about how they're held.

Cats can be finicky about how they're held.  Squish that cat.

Squish that cat.

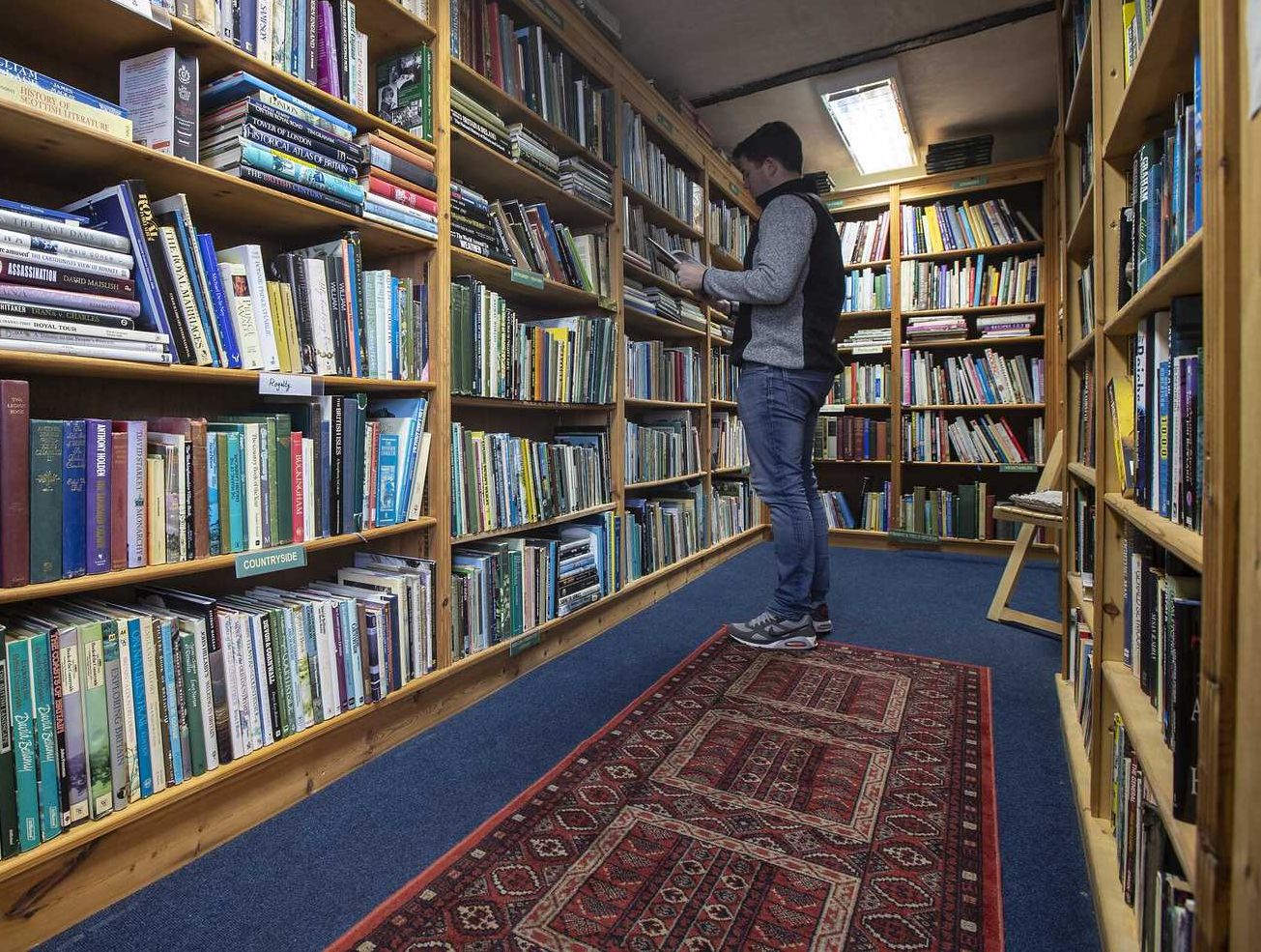

A person browses at The Open Book in Scotland.Photo Credit: Colin Tennant, Flickr

A person browses at The Open Book in Scotland.Photo Credit: Colin Tennant, Flickr The bedroom for rent above The Open Book in Scotland.Photo Credit: Colin Tennant, Flickr

The bedroom for rent above The Open Book in Scotland.Photo Credit: Colin Tennant, Flickr