Coca-Cola won't give up plastic bottles because people want them. And that's the problem.

Coca-Cola was recently named the world's largest plastic waste producer in a global plastic audit, and it appears that won't be changing any time soon. The drink giant produces about three million tons of plastic packaging each year, or the equivalent of 200,000 bottles per minute, according to the BBC.

Global studies show that 9 out of 10 plastic bottles don't get recycled. We know that a huge percentage of our plastic waste ends up in the ocean, filling up the bellies of whales and breaking down into harmful microplastics. And with changes in how and where recycling gets processed, recycling itself has proven to be a non-solution to the planet's plastic pollution problem.

In light of this information, pumping out more and more single-use plastic bottles seems like a ridiculously irresponsible move. And yet, Coca-Cola recently announced that it will be sticking with single-use plastic bottles. Their reasoning? Because people like them.

Like any business, Coca-Cola's top priority is its bottom line. Though the company has pledged to use at least 50% recycled material in its packaging by 2030 and to partner with NGOs to improve waste collection, they are beholden to the demands of its customers. As Bea Perez, Coca-Cola's head of sustainability said at the World Economic Forum, "Business won't be in business if we don't accommodate consumers."

RELATED: A dead whale just washed ashore with 88 pounds of plastic waste in its stomach. This needs to stop.

The problem is, she's right. And that, kids, is one reason why "free market environmentalism"—the idea that capitalism will eventually lead to environmental responsibility because consumers will demand it—simply doesn't work. The free market is great for a lot of things, but protecting the planet isn't one of them. Humans are creatures of habit. We like what we are familiar with and we tend to resist change, even when we know it's ideal or even necessary. If we're used to drinking soda from a lightweight, resealable plastic bottle, that's what we're going to want. Since companies are in the business of giving (or rather, selling) people what they want, the free market equation will never add up to truly sustainable change.

Companies like Coca-Cola find themselves in a position of having to appease the social movement toward sustainability while also appeasing customers who don't want to make the changes necessary to support that movement. Perez makes it sound like Coca-Cola is trying to gently nudge consumers in a more environmentally responsible direction. "As we change our bottling infrastructure, move into recycling and innovate, we also have to show the consumer what the opportunities are," she says. "They will change with us."

Is that enough, though? Not according to people on the front line of the plastic crisis. "Recent commitments by corporations like Coca-Cola, Nestlé, and PepsiCo to address the crisis unfortunately continue to rely on false solutions like replacing plastic with paper or bioplastics and relying more heavily on a broken global recycling system," Abigail Aguilar, Greenpeace Southeast Asia plastic campaign coordinator, said in a press release in October. "These strategies largely protect the outdated throwaway business model that caused the plastic pollution crisis, and will do nothing to prevent these brands from being named the top polluters again in the future."

RELATED: We haven't just paved paradise—we've plastered it in plastic

Of course, the question of what would replace plastic bottles and whether or not the alternatives are sustainable remains. Perez claims that switching to glass and aluminum may actually increase the company's carbon footprint—a related but separate issue from the plastic pollution problem.

But ultimately, the question we all need to ask ourselves is, "Whose problem is this and who needs to solve it?" Some people don't want the government to implement regulations forcing companies to adopt sustainable practices. Some put faith in individuals and industry to figure out how to get what we all want while not destroying the earth in the process. But we have plenty of evidence that consumerism (i.e., capitalism) is what got us here, and also evidence that laws and regulations can effect real change. Remember the ozone layer crisis? The Montreal Protocol of 1987, which required countries to phase out ozone-depleting substances like chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), proved successful at mitigating a clear environmental challenge. Would companies have voluntarily eliminated CFCs and found alternatives if they weren't obligated to by law? In the 1980s? When Aqua Net hair spray was at its prime? Not likely.

That being said, regulations are only effective if they are actually implemented, and the current method of making international agreements that aren't really binding can only go so far. As climate change activist Greta Thunberg keeps pointing out, the politics and processes needed to truly address our environmental crises do not currently exist. It's vital that we consult about how to actually solve problems like plastic pollution, but one thing is clear—relying on the free market isn't going to get us there.

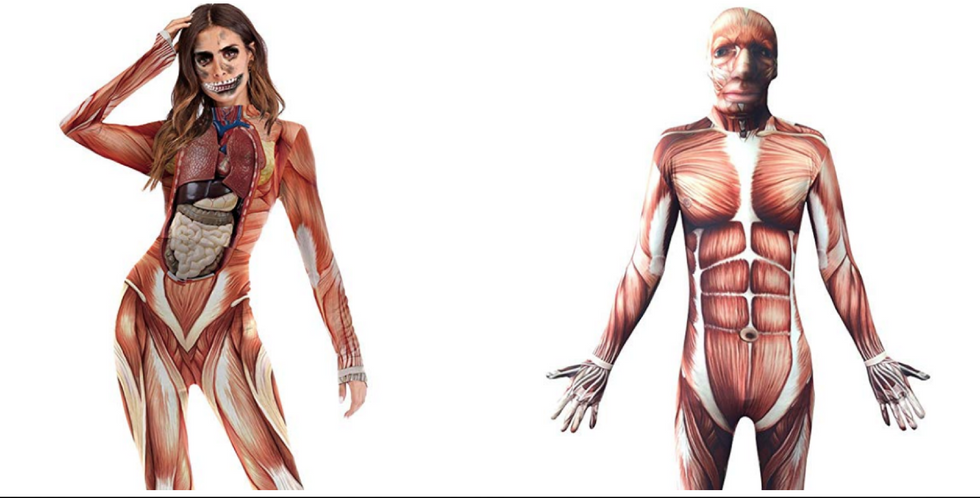

This is a teacher who cares.

This is a teacher who cares.  Halloween costume, check.

Halloween costume, check.  Patagona has always done a great job taking care of its employeesYukiko Matsuoka/Flickr

Patagona has always done a great job taking care of its employeesYukiko Matsuoka/Flickr While nursing my baby during a morning meeting the other day after a…

While nursing my baby during a morning meeting the other day after a… Not sure if Dwight Schrute would be as accomodating.

Not sure if Dwight Schrute would be as accomodating. "The conditions had turned WHAT?"

"The conditions had turned WHAT?" John Calhoun poses with his rodents inside the mouse utopia.Yoichi R Okamoto, Public Domain

John Calhoun poses with his rodents inside the mouse utopia.Yoichi R Okamoto, Public Domain Alpha male mice, anyone?

Photo by

Alpha male mice, anyone?

Photo by