For years, breast cancer patients, survivors, and their families have wondered if decades of walks, ribbons, fundraising, awareness, and dedicated activism were making a difference.

On Tuesday, a new batch of results came in.

A statistical analysis published by the American Cancer Society found that mortality rates from breast cancer fell 39% between 1989 and 2015.

The decrease amounts to 322,600 saved lives in 26 years, according to the paper's authors. Researchers attribute the drop to increased early detection and more effective treatment options.

The percentage of women over 40 who have had a mammogram in the prior two years grew from 29% in 1987 to 64% in 2015. Meanwhile, options for combatting the disease have increased, thanks to the advent of new drugs and therapies.

Hundreds of thousands of fewer people dying is good news.

The bad news is that black women continue to die from the disease at higher rates than any other demographic.

While a lower percentage of black women are dying from the disease overall, their fatality rates are still nearly 40% higher than those of white women, a rate that has remained maddeningly persistent for decades.

"The reason for the black and white difference is primarily related to economic status and lack of insurance on part of black women," Harold Freeman, former director of the American Cancer Society, told NPR in a 2014 interview. "But also, we have a health care system that doesn't treat everyone equally." He cites a lack of ability to pay for preventive care and subconscious assumptions that lead some medical professionals to ignore black women's concerns as contributing factors.

The study also found that the racial mortality gap varied heavily by region. Disparities were worst in eight mostly southern states: Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, North Carolina, Virginia, Indiana, and Michigan.

Eliminating the racial disparity when it comes to breast cancer diagnoses will require more than ribbons and walks to solve — and organizations are already rising to the challenge.

Groups like Breast Cancer Action have made racial justice a core plank, citing the need to address the disparities in education, housing, and economic power that exacerbate the mortality gap at its root.

As a stopgap, programs like the CDC's National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program help provide early detection screenings to low-income and uninsured people.

While some states indeed showed large, persistent racial disparities in mortality rates, according to the study, the gap was nearly nonexistent in several others. Three states — California, Massachusetts, and Delaware — made significant, verifiable progress in making outcomes more equal over the 26-year span.

"This means that there is light at the end of the tunnel," Carol DeSantis, lead author of the study, told The Washington Post. "Some states are showing that they can close the gap."

For the 252,710 people expected to be diagnosed with breast cancer this year — and hundreds of thousands more in the years to come — the progress in treating the disease is a welcome sign.

The work to make sure they all have an equal shot at a full recovery remains.

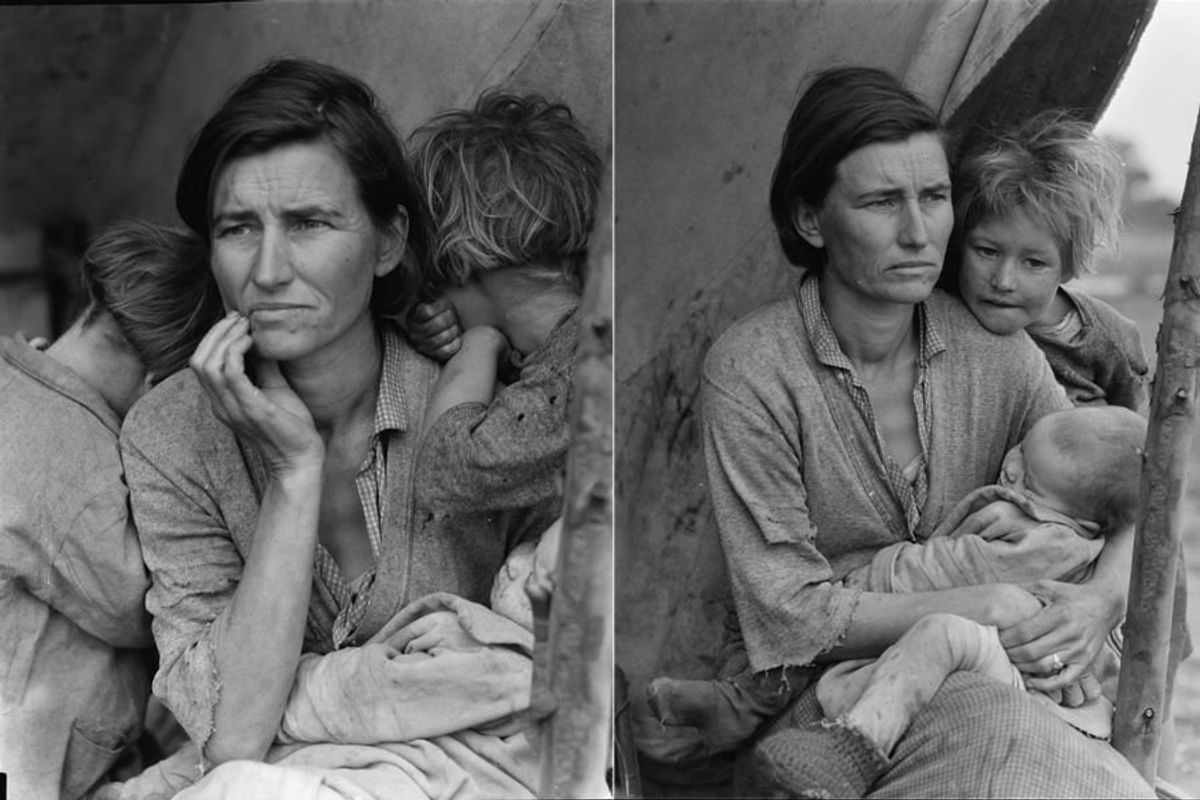

Worried mother and children during the Great Depression era. Photo by Dorthea Lange via Library of Congress

Worried mother and children during the Great Depression era. Photo by Dorthea Lange via Library of Congress  A mother reflects with her children during the Great Depression. Photo by Dorthea Lange via Library of Congress

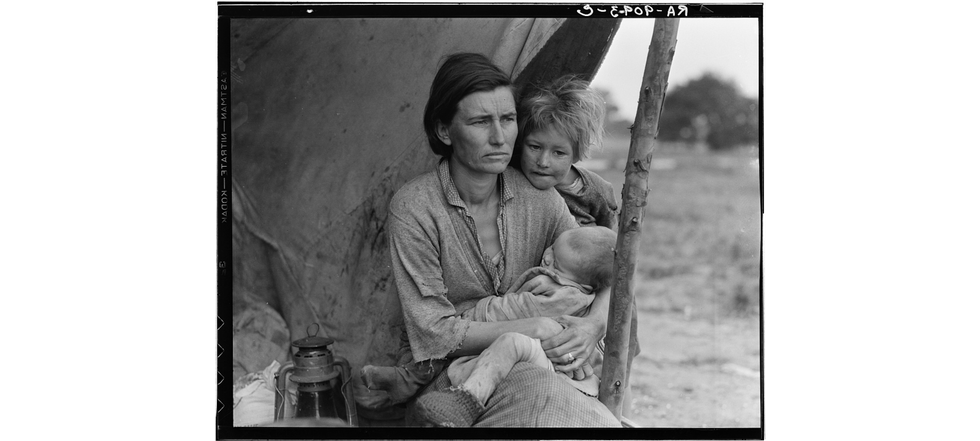

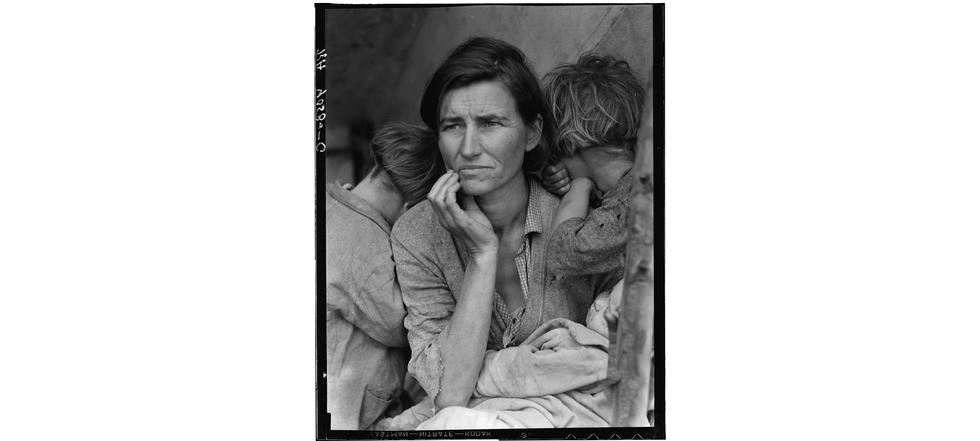

A mother reflects with her children during the Great Depression. Photo by Dorthea Lange via Library of Congress  Families on the move suffered enormous hardships during The Great Depression.Photo by Dorthea Lange via Library of Congress

Families on the move suffered enormous hardships during The Great Depression.Photo by Dorthea Lange via Library of Congress

Millennial mom struggles to organize her son's room.Image via Canva/fotostorm

Millennial mom struggles to organize her son's room.Image via Canva/fotostorm Boomer grandparents have a video call with grandkids.Image via Canva/Tima Miroshnichenko

Boomer grandparents have a video call with grandkids.Image via Canva/Tima Miroshnichenko

kenan and kel nicksplat GIF

kenan and kel nicksplat GIF  season 6 GIF

season 6 GIF

Vintage portraits of a woman and two children, showcasing elegant attire of their era.

Vintage portraits of a woman and two children, showcasing elegant attire of their era. Three friends enjoy a lively music session indoors.

Three friends enjoy a lively music session indoors.