A huge thanks to those who openly share their mental illnesses. You saved my daughter.

We didn't know that our teen daughter had an actual mental illness. We just knew that she felt extra nervous sometimes — and it was getting worse.

She didn't get excited nervous, like you'd feel before you go on a roller coaster, or uncertain nervous, like when you're facing a big decision. Hers was the debilitating kind of nervous, the kind that takes over your whole body and brain. The kind where instead of fight or flight, you freeze, and nothing anyone says seems to help.

It took us awhile to name it "anxiety" and even longer to discover that our bright, sweet girl was experiencing emetophobia, a specific anxiety disorder revolving around a fear of throwing up.

You may never have heard of emetophobia — I hadn't. It's a largely unknown but not uncommon anxiety disorder. And it is treatable, but it requires a specific kind of treatment.

The only reason we figured any of this out is because of people who were willing to openly share their stories about their own struggles. Hearing and reading about other people's experiences probably saved our daughter's life.

Getting a correct diagnosis was key — and if it weren't for other people being open about their mental health issues, I don't know that we would have gotten one.

The first two therapists we took our daughter to treated her for generalized anxiety. I don't know if they didn't ask the right questions or if they weren't familiar enough to spot the signs of emetophobia or if our daughter just wasn't forthcoming about her true fears. All I know is that the treatment methods they used barely made a dent in her anxiety.

It wasn't until I started noticing a pattern to our daughter's nervous behaviors that I realized we'd missed something crucial.

What if we talked about physical health the absurd way we talk about mental health?

Posted by ATTN: on Friday, May 26, 2017

She wouldn't say the word "vomit" and couldn't handle hearing stories about people puking. If she heard that someone we knew had been sick, the first words out of her mouth were a panicked "What kind of sick?" She constantly checked expiration dates on packages and asked us if food was OK to eat. She became obsessive about handwashing.

Then it got worse. Over a matter of months, we watched our travel-loving 16-year-old become nervous about being far from home, the radius inside which she felt safe growing smaller and smaller. Eventually, going to the next town over — 20 minutes away — became an enormous hurdle. She was taking community college classes, and getting to school became a daily battle with her frequently feeling dizzy or nauseous as soon as we got there. Sometimes it would take her 10 minutes to make herself get out of the car. Sometimes she simply couldn't, and we'd have to turn around and go home. No amount of logic or reason could talk her down from her mental ledge.

Finally, one day I asked her, "Do all of your anxieties have to do with not wanting to throw up?" She thought for about 10 seconds and said, "Yes."

I googled "fear of throwing up" and found the term "emetophobia." And from there, I discovered a whole world of people just like my daughter.

I'd never recommend diagnosing with Dr. Google. But reading people's stories helped us pinpoint our daughter's disorder and made a huge difference in her recovery.

The internet gets demonized for good reason sometimes, but it really is an incredible tool when used well.

I first read an article about an emetophobic teen whose symptoms and behaviors matched our daughter's precisely. Then I found websites dedicated to people with the condition with detailed descriptions of symptoms and behaviors and more people's stories.

Everything I read made me 100% sure this was what we were dealing with.

I learned that emetophobia is frequently misdiagnosed as generalized anxiety, an eating disorder, or agoraphobia because emetophobes don't like to talk about feeling sick. Unless a therapist knows what to ask or what to look for, it's easy to miss. And many therapists aren't familiar enough with emetophobia to diagnose and treat it properly anyway. It took us a while to find a therapist who had even heard of it.

For some people, the fear spirals out of control. They can't brush off the facts that any food at any time could be contaminated with food-borne illness and that any person at any time could be walking around with a contagious stomach virus. Every stomach sensation — hunger, digestion, gas, nervousness — starts being interpreted as nausea, so they worry all the time that they're on the verge of getting sick.

At its most extreme, emetophobia causes its sufferers to feel constant anxiety about the most normal, common things in life — people and food — and to live in constant fear that their body is about to betray them. There's no getting away from it, and the more aware they become, the more they feel the need to hide away from the world.

That's what we saw happening to our child.

I only learned all of this, though, because of people who were willing to openly share their struggles. Reading emetophobia stories brought our daughter's issues to light, helped us know we weren't alone, and let us know we might have to persevere for a while before we found real help.

I can't tell you the relief in my heart when, after calling half a dozen therapists, an angel named Jeannie finally said, "Oh yes, I've treated several people with that condition. I can totally help your daughter."

There is no more terrifying feeling than watching your child suffer and being at a loss about how to help them. And there is no greater joy than watching your child get better — which our daughter has. After just a few months of therapy with Jeannie, she was markedly better. Now, almost a year later, she is living a normal life again.

Thanks to people sharing their struggles, my daughter has learned at a relatively young age how to reject the stigma that so often accompanies mental health issues.

I asked my daughter if she would be OK with me writing about her emetophobia journey, and she said yes. Having seen how much people's stories helped her, she wants to help others who might feel like they're the only ones suffering.

She has been impressively open about her disorder. Our daughter has always been an excellent student, but during the worst of her symptoms, she'd miss classes or be late on assignments because the anxiety overtook everything. When she wrote to her teachers about making up the work, she told them why — not as an excuse but as the true explanation for why she was slipping.

And you know what? The vast majority of her instructors were completely understanding. Several told her they also struggled with some form of mental illness, and others said they had loved ones who did. There was no judgment. One teacher was unwavering on due dates (that's life), but I was blown away by how supportive most were.

So thank you to the brave souls who have blazed the trail for my daughter, who openly and willingly share their mental health struggles, and who help the world understand that mental illness is nothing to be ashamed of or embarrassed about. You helped my daughter reclaim her life, and I am immensely proud that she can now count herself among you.

My daughter and I on a cross-country flight that would have been unthinkable to her six months before it. Thank God for good therapy. Photo by Annie Reneau.

If any of this sounds familiar and you think you or a loved one might be struggling with emetophobia, we found www.emetophobiahelp.org and www.emetophobiaresource.org to be immensely helpful.

For information about getting help with other mental health issues, check out the National Alliance on Mental Health's resource page.

Rihanna Nails GIF

Rihanna Nails GIF A photo of Helen and Bill in their uniformsImages provided by Drew Coyle

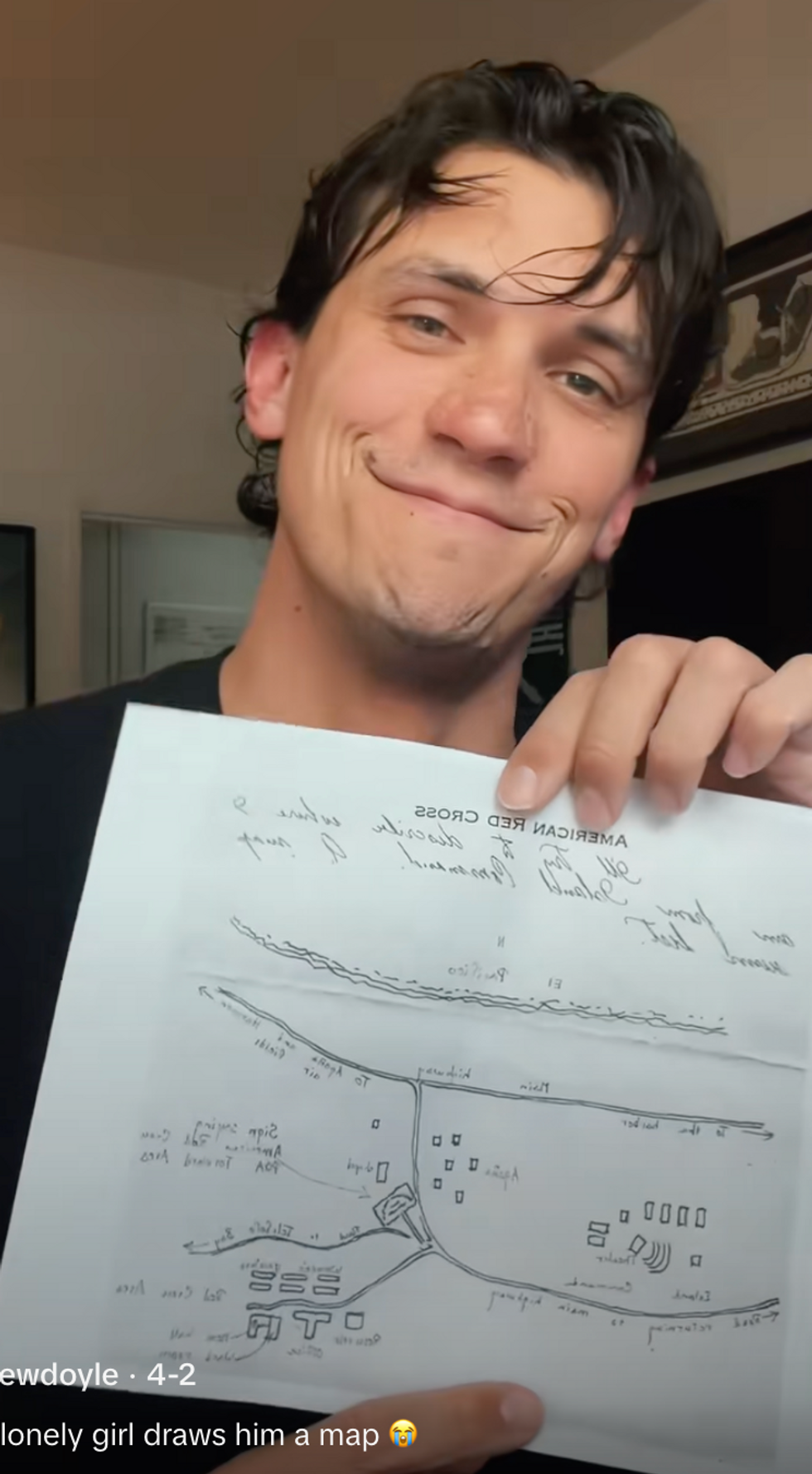

A photo of Helen and Bill in their uniformsImages provided by Drew Coyle The map provided by Helen to Bill@crewdoyle/

The map provided by Helen to Bill@crewdoyle/ Helen and Bill, happy and and content, and oh so in love. Image from Drew Coyle

Helen and Bill, happy and and content, and oh so in love. Image from Drew Coyle Good luck trying to catch a gazelle.

Good luck trying to catch a gazelle. Chickens will eat just about anything.

Chickens will eat just about anything. There's actually a big difference between horses and zebras besides just the stripes.

There's actually a big difference between horses and zebras besides just the stripes. A photo of a portable carbon monoxide detector from Amazon

A photo of a portable carbon monoxide detector from Amazon