At 4:30 a.m. on Sept. 12, 2017, Roy Guill woke up to a Facebook message from a man he'd never met.

The man, Eric Delman, explained that he'd been going through some stuff from 9/11 for the previous day's anniversary. He wanted to know if Guill was from Staten Island.

But it wasn't Delman's message that struck Guill. It was what Delman was wearing in his profile photo: a yellow, coal miner's helmet with a bracket on the front where the headlamp used to be and a dent in the brim.

“It was a picture of him at Ground Zero on the pile, and I looked at the picture for a second and I thought, 'Holy shit. Is that Papaw’s helmet?'"

Photo via Eric Delman.

In the wee hours of Sept. 11, 2001, Guill was passed out on his boss's couch in their midtown Manhattan office.

He was still asleep when his boss woke him with the news of the attacks a few dozen blocks away.

"The first thing I thought was, 'But it’s such a beautiful day,'" he recalls.

Like thousands of other New Yorkers living and working in the city that day, Guill's account is one of having "just missed" being swallowed up in the carnage. He had stayed the night at work after pulling a long overnight shift. Otherwise, he might have been stranded on the subway under the towers when the planes struck.

Instead, he and a colleague fled the city in a minivan they had rented the previous day.

Guill traveled nearly 200 miles that afternoon: north to Westchester County, south to Perth Amboy, New Jersey, north again to the Tappan Zee Bridge, east to Queens, and south to Brooklyn. When he finally rolled across the Verrazano, it was just after midnight on Sept. 12.

"By that point, the smell had hit us. We rolled down our window to talk to a cop, and you could smell the fire," he says.

The next morning, he and his wife Julia lined up near their Staten Island home to give blood. A nurse turned them away. "There was no one to give blood to," he recalled on Facebook.

Instead, they stocked up on soap, deodorant, and socks from a local dollar store — the only store within walking distance — and prepared to drop them at a collection point near the ferry terminal. On their way out of the house, they stopped at a coat rack by the door. The rack was covered in hats, scarves, jackets — and an an odd item that caught Guill's eye.

A yellow coal mining helmet.

He picked up a pen and a piece of paper.

When Eric Delman, an NYPD officer, arrived downtown Manhattan the afternoon of the attacks, the area was already a ruin.

"It was horrible. That stench of a lot of smoke, and that very bad — the smoke and the smell and the death," he recalls.

The following day — or maybe the day after — Delman reported to a supply tent. It was full of respirators, work clothing, boots, and helmets. He picked out one that he liked, an "old-style" yellow miner's cap.

Delman worked on a bucket brigade. He cleared stones. Rebar. Eventually, body parts. He would come home with his clothes covered in a thick gray dust. His wife washed them every day. He seemed haunted.

The yellow miner's helmet stayed with him the whole time. As he dug through "the pile," the mass of rubble left behind when the towers crumbled, the helmet was there. As the news of dead friends trickled in like bilge water, the helmet was there. After Delman's tour at Ground Zero ended, the helmet made its way to a shelf in his garage. Sometimes, he would take it down to look at it. One day, as he was turning it over in his hands, he gasped.

"There's a note!"

Photo by Eric Delman.

A small, creased tab of white paper was stuck to the inside. He had never noticed it before.

"To whoever wears this," it read. "This was my grandfather's helmet in the mines of Kentucky. I hope it protects you well. You are all heroes."

The note was signed, "Roy and Julia Guill."

Guill's papaw, Roy W. Guill, was born, grew up, raised seven children, worked, and died in Carrsville, Kentucky.

One of the few pictures of Papaw that remains was taken before his brief detour to the Pacific theater of World War II, where he served as a combat engineer. He never talked about it.

Roy W. Guill. Photo via Roy Guill.

Papaw wore bib overalls. Some nights, on his way home, he would save his granddaughter Angi a treat leftover from his lunchpail. When Guill told him he wanted to chew tobacco, Papaw tried to dissuade him by giving him a pinch of Prince Albert. He warned him not to swallow it — about three seconds too late.

When Papaw woke up at 5 a.m. to go to work, Guill would sit with him, nodding off between bites of pancake as his grandfather suited up in a side room near a potbellied stove. When he went off to the mine, the helmet went with him.

Papaw passed away at age 81, when Guill was 14. After the funeral, Guill's father gave his grief-stricken son the helmet.

It was the only physical reminder of his grandfather Guill possessed.

Or, it had been.

On Sept. 11, 2017, Guill took the day off from work — as he occasionally does on the anniversary of the attacks.

He rarely talks about what he saw that day 16 years earlier.

"It’s so hard, and emotionally it’s such a slog, but we were so lucky," he says.

The Facebook message from Delman was like a bolt out of the blue.

After Guill confirmed that, yes, he was from Staten Island, Delman sent a photo: the same photo Guill had seen in Delman's profile picture.

"Does this look familiar?" Delman wrote. "This is me at the time."

Photo via Eric Delman.

The photo of Delman wearing the helmet had been taken by a fellow officer shortly after the attacks. When that friend fell ill 10 years later, he found and sent the photo to Delman. This year, Delman made it his profile photo to commemorate the anniversary.

Guill had often wondered what happened to Papaw's hard hat from the mines. He worried it had been thrown out, that it hadn't been up to code, or had been overlooked in a vast sea of donated tools and gear. Here, finally, was proof: Not only had someone — Delman — used it, it had meant enough to him that he kept it.

"Honestly, I sat here in my dining room and bawled my eyes out," Guill says.

Delman is now a lieutenant who oversees the 88th Precinct's Special Operations Unit. His time at Ground Zero left him with nodules in his lungs. He gets them checked every year. So far, so good.

He told Guill to expect the helmet on his doorstep soon.

"There’s a box on my kitchen table for me to send it back," he says. Before he does, he wants to add a few touches. A T-shirt, perhaps, with some patches. Some coins. Maybe both.

It may take a while to reach its destination. Guill left New York 13 years ago. He lives in Las Vegas now. He imagines it will show up in about a week.

Guill doesn't know if he's prepared. But his papaw's helmet is coming home.

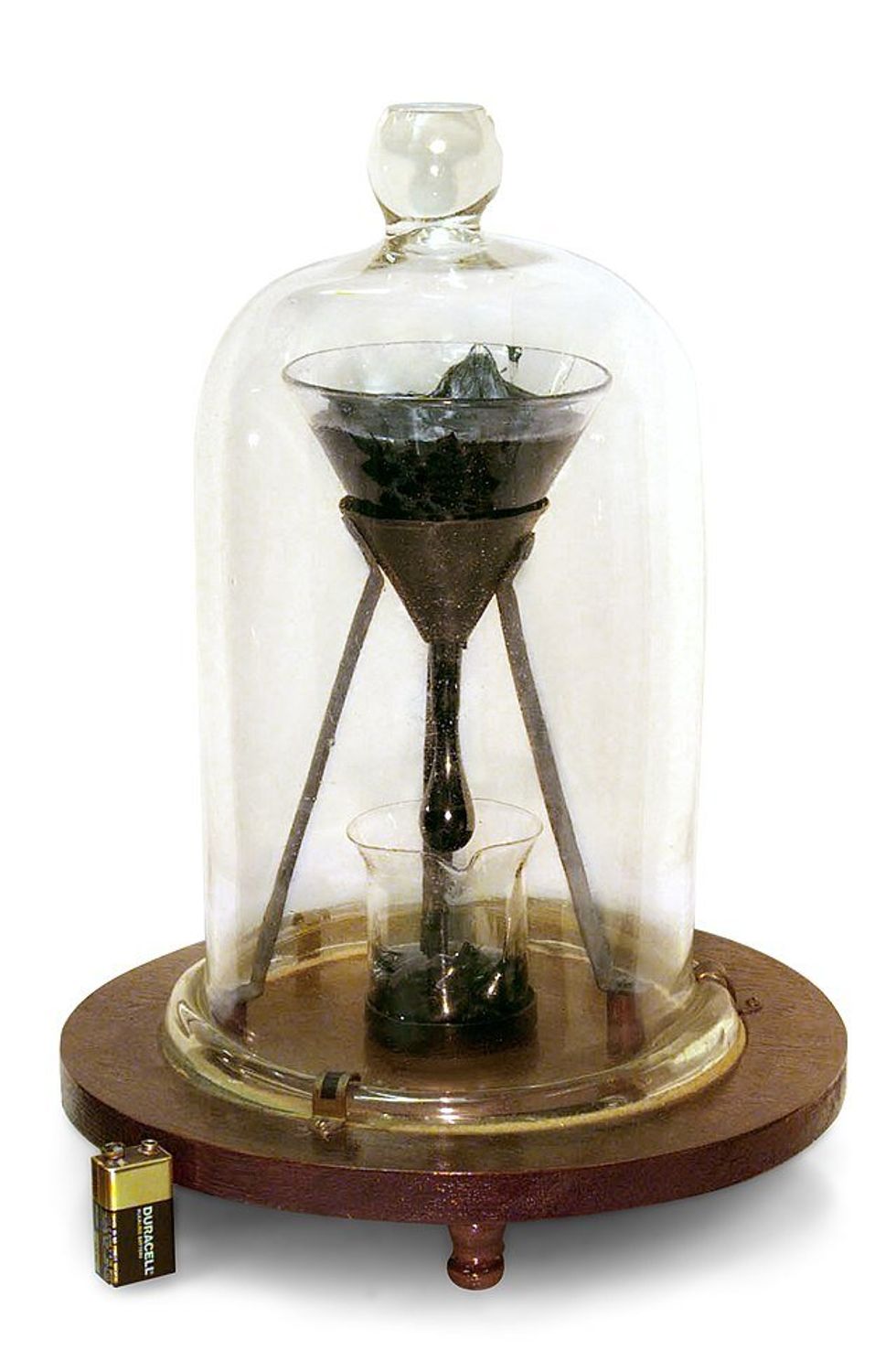

Pitch moves so slowly it can't be seen to be moving with the naked eye until it prepares to drop. Battery for size reference.

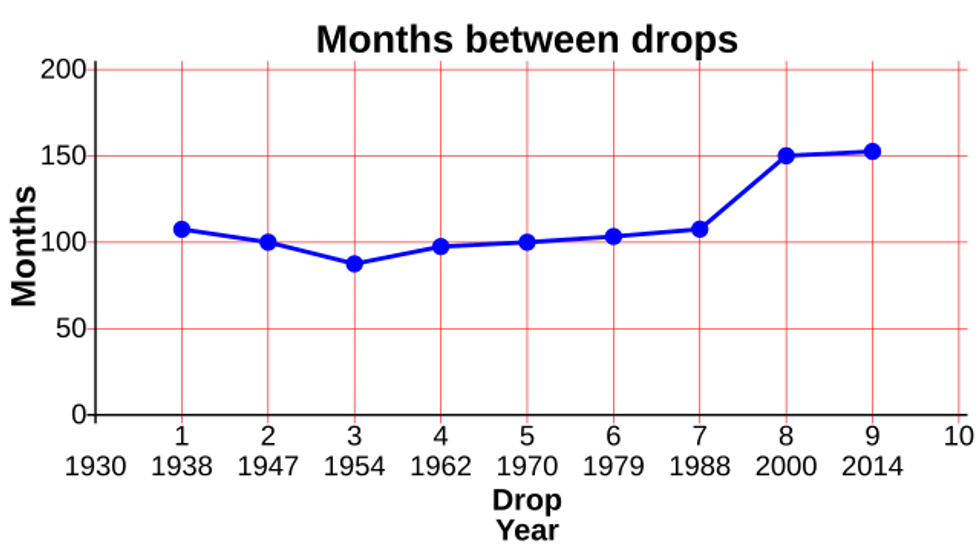

Pitch moves so slowly it can't be seen to be moving with the naked eye until it prepares to drop. Battery for size reference. The first seven drops fell around 8 years apart. Then the building got air conditioning and the intervals changed to around 13 years.

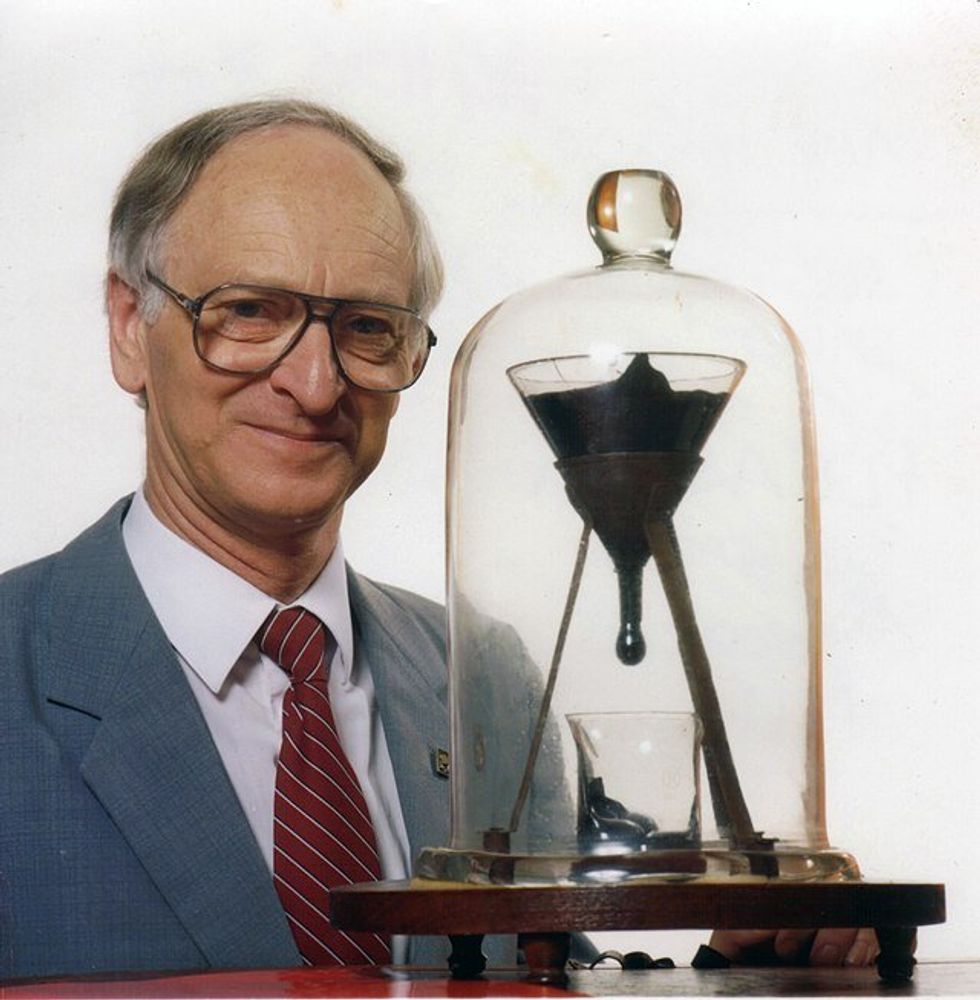

The first seven drops fell around 8 years apart. Then the building got air conditioning and the intervals changed to around 13 years. John Mainstone, the second custodian of the Pitch Drop Experiment, with the funnel in 1990.

John Mainstone, the second custodian of the Pitch Drop Experiment, with the funnel in 1990. Who wouldn't want to recreate this?

Who wouldn't want to recreate this? A father does his daughter's hair

A father does his daughter's hair A father plays chess with his daughter

A father plays chess with his daughter A dad hula hoops with his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad hula hoops with his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. A dad talks to his daughter while working at his deskAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad talks to his daughter while working at his deskAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. A dad performs a puppet show for his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad performs a puppet show for his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. A dad walks with his daughter on his backAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad walks with his daughter on his backAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. a dad carries a suitcase that his daughter holds onto

a dad carries a suitcase that his daughter holds onto A dad holds his sleeping daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad holds his sleeping daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. A superhero dad looks over his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A superhero dad looks over his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. A dad takes the small corner of the bed with his dauthterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad takes the small corner of the bed with his dauthterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. Being regular guests haas helped make us good Airbnb hosts.

Being regular guests haas helped make us good Airbnb hosts. Chasing Tom And Jerry GIF by Max

Chasing Tom And Jerry GIF by Max Asking guests to stip the sheets saves almost no time and costs a lot in goodwill.

Asking guests to stip the sheets saves almost no time and costs a lot in goodwill. Most guests are try to leave the place as they found it, standard cleaning routine aside.

Most guests are try to leave the place as they found it, standard cleaning routine aside.  A happily married couple.via

A happily married couple.via  A couple getting married.via

A couple getting married.via  Kingboiza asks men about marriage.

Kingboiza asks men about marriage.