When Shila Burney's 17-year-old son Michael leaves the house, she insists that his phone's GPS is turned on.

Burney trusts her son and his friends, but she doesn't make this request lightly.

The Burneys are black. As a mother of a black son, Shila worries about the strangers and situations Michael may run into that he can't control. If something goes wrong, she says, "How quickly can I get there — to him?"

When the Atlanta-area mom of four speaks about motherhood, there's a passion and protective fierceness in her voice.

"Everyone thinks just because we're strong, black women, we walk around emotionless," Burney says. "That is not the case. We care deeply about our kids. We'll do anything in the world for them, and we don't want anybody else hurting them."

The Burneys. Photo used with permission.

We often only hear from black moms after their children are lost to senseless acts of violence.

It's frequent and unsettlingly repetitive. A shooting. A grieving mother. Brief outrage. A call for peace. Another hashtag. A grim reminder of a family torn apart.

It's happened 95 times this year so far.95 black people have been killed by police in 2017.

We hear this pain too often: "Our family will never be the same; the kids will never be the same," said the mother of Jordan Edwards, a 15-year-old killed by a police officer outside Dallas this May. It happened again with the families of Quanice Hayes, Tony Robinson, and Laquan McDonald.

There was also Richard Collins III, a black college senior and would-be second lieutenant in the Army who was stabbed to death by a stranger just days before graduation. Even though she'd never met him, the news of Richard's murder shook Burney to her core, and not for the first time.

"All those emotions start coming again," she says.

With Collins' murder, many parents saw in him their own children of color — bright, driven, talented — and wonder how they can possibly protect them.

Police and the FBI are investigating the killing of Collins as a possible hate crime. The suspect, Sean Urbanski, was a member of a racist Facebook group. Photo by U.S. Army via Associated Press.

"I've never sat down with my kid and explained to them anything about the police, because to me, they weren't supposed to have any interactions with the police," Burney says. She tells her children to be good kids, to do what they're supposed to do. "You may get stopped for a ticket, but I had no rules for when you get stopped. 'Be respectful' — that's all I had."

When Burney heard of Sandra Bland's death, all that changed. She wept, imagining her own daughter alone, at the mercy of an aggressive police officer with no way to protect herself. Burney raised her kids with the guidance of "be respectful." Now, respect didn't seem to matter.

Photo by iStock.

There's a difficult push and pull that black moms live with: wanting their kids to be kids and, at the same time, protecting them from a society that doesn't always love them back.

Sheila Higginson is white. Her husband, Felipe, is black. She struggles with the same fears for their two teenaged boys in Brooklyn.

"I want to make sure they're aware of the hatred ... that there are people who truly don't want them to exist," says Higginson. She wants her sons to believe they're special, that they can be anything they want. But it's not that easy.

"There's a group of the world that sees them as young, teenage, black boys and sees: threat," she says. "That's a really sad thing to have to tell your kids."

Sheila Higginson's husband, Felipe (left), and sons Kai (center) and Jake at a Mets game. Photo via Sheila Higginson, used with permission.

Raising and parenting a child of color in America requires emotional intelligence, labor, and grit that's rarely acknowledged.

It's talking to children about why they can't go out with their hoodies up or du-rags on. Explaining why hair or dress codes at school may be written to disproportionately punish them. Practicing how to respond to police officers or authority figures when they're out with their friends. Discussing why some people may see them as a threat, even if they're only in middle school.

These are conversations most white families will never have. Each one is exhausting but necessary.

"You have to kind of shatter the snow globe," Higginson says. "As a mother, you have to support your kids through that moment of disillusionment with the world. But I really felt unprepared for this level of it."

The Higginsons at a party. Photo via Sheila Higginson, used with permission.

"Growing up in Brooklyn ... my kids were in a bubble," she says — disconnected from some of the worst kinds of racism in our country. But lately, that's changed.

After the election of President Donald Trump, things have gotten harder.

"It wasn't a daily thing. Right now, it is. It's so shocking that it's here. In Brooklyn. It's mind-boggling," she says. She's seen a rise in racist vitriol in her neighborhood, especially against Mexicans and recent Muslim immigrants.

Protesters near Trump Tower in Chicago. Photo by Scott Olson/Getty Images.

Both moms have hope that things can improve, but only if we start listening to one another.

When white families get media coverage day after day when something happens to their children, Burney feels frustrated. Black parents hurt too, but their stories are often under-covered and under-considered.

"We have stories; our stories need to be told. Don't forget us," she says, the protective passion of a fierce and loving mom, in a world hostile to her children, stirring in her voice again.

People join mothers from around the country who lost their children to police violence to protest in front of the Justice Department at the Million Mom March in 2015. Photo by Gabriella Demczuk/Getty Images.

Right now, children of color — particularly black children — are under attack from all sides. If one child hurts, we should all feel it.

"Every single mother shares this feeling of wanting their kids to feel safe and protected and able to just be kids," Higginson says. "How can you be a mother and not understand that? How can you be a mother and not understand we're saying our kids areunsafe, not just feel unsafe. Are unsafe."

A candlelight vigil for Jamyla Bolden in Ferguson, Missouri, in 2015. Bolden, 9, was killed by a stray bullet from a drive-by shooting while doing her homework in her home. Photo by Michael B. Thomas/ Getty Images.

A father does his daughter's hair

A father does his daughter's hair A father plays chess with his daughter

A father plays chess with his daughter A dad hula hoops with his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad hula hoops with his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. A dad talks to his daughter while working at his deskAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad talks to his daughter while working at his deskAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. A dad performs a puppet show for his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad performs a puppet show for his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. A dad walks with his daughter on his backAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad walks with his daughter on his backAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. a dad carries a suitcase that his daughter holds onto

a dad carries a suitcase that his daughter holds onto A dad holds his sleeping daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad holds his sleeping daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. A superhero dad looks over his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A superhero dad looks over his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. A dad takes the small corner of the bed with his dauthterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad takes the small corner of the bed with his dauthterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. Season 8 Nbc GIF by The Office

Season 8 Nbc GIF by The Office Figuring out our finances may be getting easier.

Photo by

Figuring out our finances may be getting easier.

Photo by  Plumbing Plumber GIF by Family Guy

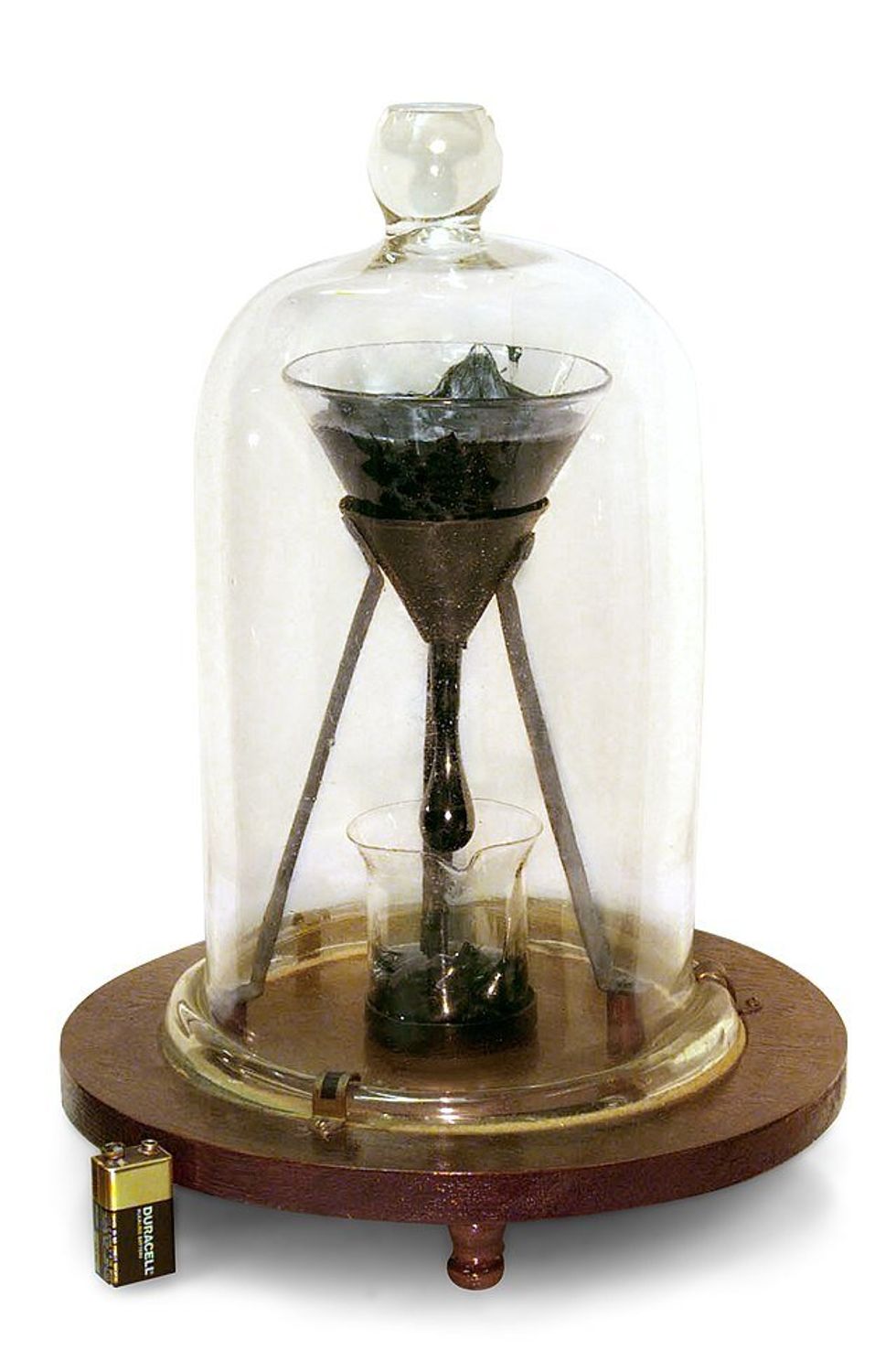

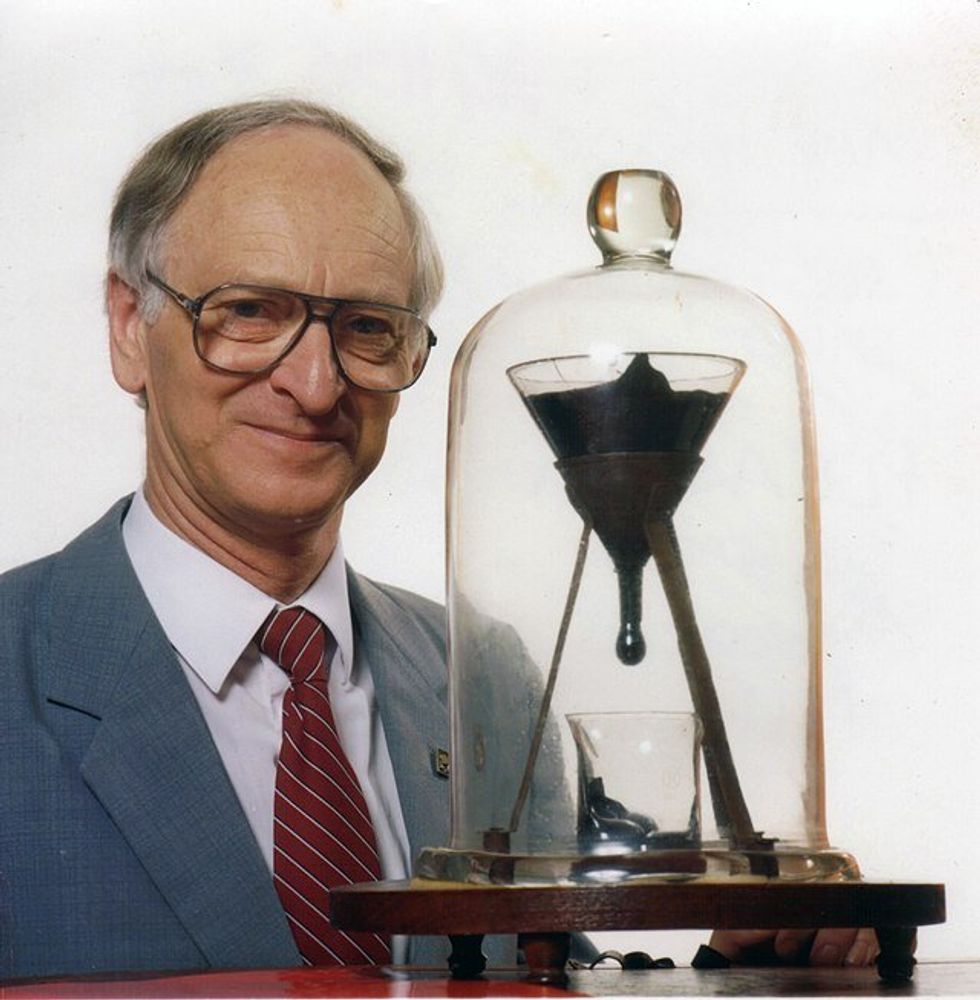

Plumbing Plumber GIF by Family Guy Pitch moves so slowly it can't be seen to be moving with the naked eye until it prepares to drop. Battery for size reference.

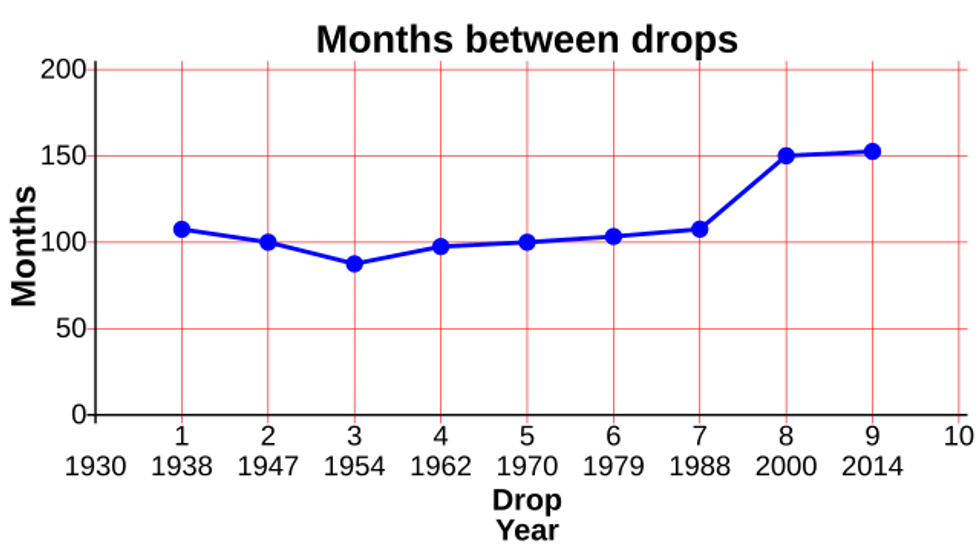

Pitch moves so slowly it can't be seen to be moving with the naked eye until it prepares to drop. Battery for size reference. The first seven drops fell around 8 years apart. Then the building got air conditioning and the intervals changed to around 13 years.

The first seven drops fell around 8 years apart. Then the building got air conditioning and the intervals changed to around 13 years. John Mainstone, the second custodian of the Pitch Drop Experiment, with the funnel in 1990.

John Mainstone, the second custodian of the Pitch Drop Experiment, with the funnel in 1990. The Alhambra sits atop a plateau overlooking Granada, Spain.

The Alhambra sits atop a plateau overlooking Granada, Spain. Fountain of the Lions at the Alhambra, Granada

Fountain of the Lions at the Alhambra, Granada Remains of baths inside the Alhambra Alcazaba

Remains of baths inside the Alhambra Alcazaba