Why would someone cross the border illegally? Hear one man's harrowing story.

When your first day in America means hiding from Border Patrol.

José Miguel Cáceres is a 20-year-old who left Guatemala earlier this year to seek asylum in the U.S.

Here's the story of his first 24 hours at the border, in his own words.

First we arrived there, Camargo. That's the Mexican border with the United States. We were there in a house for four days.

It was a normal house. There were children and their mom and her husband there. Like a normal family. There were six of us, only men. Three of us who were there were from Guatemala, one Nicaraguan and two Salvadorans. I'm 20 years old. The others were 20, 22, 25, all the way up to 40.

We were eating well and able to wash ourselves and everything during those four days. We had everything we needed. On the fourth day, they decided to get us to cross the river.

We left the house in Camargo at five in the afternoon. They picked us up in a white truck and it was only a five-minute ride to the river. We sat in the back and we were covered. We had to be covered because if the army had seen us, they might have killed us or handed us over to immigration.

Once we got to the riverbank, we got out and started to walk. That's when the famous immigration helicopter showed up, the one from the United States.

The helicopter went around in a circle and then lowered a little when it saw us. From there, we dove down on the ground where there were some hills, and we stayed down there a little while. There were lots of plants and thorns.

Illustrations by Kitty Curran/Upworthy

The people from immigration weren't able to see us. The helicopter rose back up, and then from there, it did another circle. That was when we got up and started to run. We ran toward the riverbank so that they wouldn't see where we were. I imagine that maybe they let us go because it's Mexican territory and they weren't able to come down and arrest us. And it was just six people.

When we were watching the helicopter, we were all nervous, all tense. A few of the guys I was with had already been in the U.S. They knew what would happen, how we would suffer if we were caught before we crossed. It's better that they catch you here in the United States than catch you in Mexico. Because throughout Mexico there's a lot of corruption and the police work together with the drug traffickers.

I was coming to the United States because the gangs were extorting me in my neighborhood in Guatemala.

A group of people wanted me to give them money. I was working at McDonald's and they would show up there and ask for money. They would also call my cell phone and home. There were times when they actually came to my neighborhood.

I paid them 3,000 quetzales once, which is about $400. I was a target because I was working and because my family lived in the United States. When they asked me to pay again, I refused. Then they threatened me. They told me they wanted money and if I didn't give it, they were going to kill me. So I spoke with my parents and they immediately sent to bring me here. This was the best option.

I was thinking a lot about my family, my friends, and my girlfriend and her family in Guatemala during the trip. I knew that wherever I was, they were always there with me and supporting me.

So we started running again after the helicopter left. We ran and then we found ourselves another little piece of a hill. Then from there, our guide explained what we were going to do. And he told us that we were going to walk for 15 minutes, to the right.

“OK, 15 minutes," we told ourselves. But 15 minutes became an hour and a half. We walked a good bit, maybe five miles along the river.

We had two guides. They were Mexican, normal people, young, just like us. There was one who had gotten caught maybe a month before. He had a visa or residency here in the United States. But when they caught him bringing people over, they took it away.

When we reached the point where we would cross the river to the United States, we started to inflate the raft.

We were going to inflate it with a pump they brought, but they lost a piece and they had to go back to look for it. We tried to blow it up ourselves, but it was too big. So better to go back and look for the missing piece.

We stayed there, hidden in the brush until one of them came back with the piece and they started to inflate it. "It's good," they told us.

There was just one raft for everyone, for eight people. We needed a raft because the river is very deep and the current is very strong. And the river has whirlpools inside it. That's why many people aren't able to cross. Because they try to swim, but it's too strong.

At that moment, what we were most afraid of was that someone might fall off the raft and into the river. I can't swim, but they gave us life vests.

On one hand, I felt calm because I was using a raft. But on the other hand, I was nervous because an immigration boat could come at any time. And they could arrest us or something.

The raft seemed safe, but it's not.

If the raft hits a wire or maybe a pointy tree branch, even just once, then it can break. Yes, it can break. Then it would send everyone down into the river. We would sink.

We climbed into the raft. There was a person who was rowing and he started to row. It took maybe five minutes to cross and we arrived on the other side. When we finished crossing, it was already dark.

On the other side of the river, the American side, there were woods.

There were plants, trees, and roots all over. We started to climb up a little hill and then they told us to wait a moment.

We waited for five minutes or so and then they gave us instructions for what to do. They told us, "Look, we're going to walk for 15 minutes, that's it. And then someone will show up who will get us in a pickup. The pickup will be there already, waiting. Just a little further."

The walk wasn't hard because there was a dirt road. I think it was for agricultural workers. There are a lot of agricultural companies there, all sorts of companies. Pickup trucks go by there.

When we started to walk, it was around 9 p.m., so there wasn't any light. The sun was down.

Everyone was silent. The one person who said anything was the guide.

He told us what we had to do. He told us first that he wanted us to stay quiet, that we should walk in a line, and that the last one in the back was going to look to make sure no one was coming from behind. If the last person sees someone coming, then warn him.

He said that if we got in a row and went quickly that everything was going to be OK. And that we were going to be with our families soon. They were almost like professionals. I think they cross two groups each day, one in the morning and the other one in the afternoon. They weren't with us for the whole trip. They just cross people over, that's it.

We walked the 15 minutes. Then a guide told us there was a light, and we threw ourselves down in the woods out of fear.

We were worried that someone would be able to see us and was going to arrest us or something like that. There were more thorns on the ground, but when you're in this situation, you don't remember that there are thorns on the ground. We just threw ourselves down.

But then the light passed and they told us, "No, no. It's gone." We continued walking and we arrived at the place where the pickup was supposed to be. But the pickup still hadn't arrived and the guides were worried. They were afraid, too, because if immigration came, the agents would go for them, too.

After all we had gone through, there was a moment of tension because the pickup wasn't where it should have been. So the guides started to call and call and call. We thought about going back.

We were there for 10 minutes, not a long time. But in 10 minutes, you can think about a lot of things. Then suddenly the pickup arrived. "You need to go to the pickup," he said, "but you should go running." The truck was a red GMC and it already had the doors open for us.

We went running to the pickup and since it was night, no one saw us.

We all got in. From there, the driver turned around and we went to a city called Rio Grande.

The last time I had eaten was in the afternoon, but I wasn't hungry. When this is happening, you don't remember if you're hungry or thirsty. All you want is to get out of the situation.

Luckily, we weren't wet. We only got our feet wet, since when we put the raft in the water, we had to climb up. And it was March, so the weather was good. It was a nice day, not too cold, not too hot. I remember the day, it was March 9.

I wore a black sweatshirt, with jeans, a T-shirt, and sneakers. That's it, they wouldn't let you carry more clothes. I wore them for the whole trip, 10 days.

When we arrived in Rio Grande, we were in a house for about 15 minutes.

It was a nice house and there was a family there. They were good people and they asked us if we wanted something to drink, a soda or a beer. They gave us crackers, something small. They asked if we wanted water, purified water.

The house was pretty big. It had more than one level and maybe five or six rooms, with three trucks parked outside. There was a man, his wife, and a little girl. The man was very nice. They spoke English and they barely spoke Spanish. But two of the guys I was with spoke a little English.

And from there, another young man arrived in a truck and told us, "OK, we're going to McAllen." And then he got us from the house and we got in the truck, a Honda CRV.

We traveled to McAllen and he told us that no matter what — even if the police stop us — we should say we don't know him, that we were just hitchhiking.

There were a lot of police on the highway. We passed 10 patrol cars at one point. We thought they were going to stop us, but they had stopped another person. They had just found a shipment of marijuana and we saw the packages. That's probably what made it so easy for us to pass by at that moment.

The driver was relaxed, though. He was from the United States, but he spoke Spanish. He was 29 or 30 and was wearing boots and a big hat.

It was about 20 minutes from where we were to McAllen. He was playing music and everything. He played Spanish rock music. Maná.

From there, they took us to an auto mechanic shop, where there they told us that two of us would go to an apartment with one guy and the other four would go with another guy. So this is where the group separated.

I went with my friend, the other Guatemalan. They were worried that immigration might check on one of the apartments. This way, if they found one group, they wouldn't get all six of us.

They took us to the apartment, my friend and me.

The apartment wasn't so big. It just had two rooms. One was where the person who was coordinating everything lived. The boss of the operation. In the other room, that was for three of us: me, the other Guatemalan, and a Honduran.

When we arrived at the apartment, it was like 11 p.m. The the Honduran gave us clothes to change into because we were dirty. He told us that the next day we could go to the laundromat.

The room had a television with cable, but no decorations. Just a mattress for him, a mattress for us, a television, and nothing else. That was the room. Oh, and a microwave.

He asked if we were hungry. "Yes, of course," we told him. Then he went to get us food from a restaurant.

We had tacos with beans, a different type than in Mexico. But at that point, anything would have been good. We were really hungry. We stuffed ourselves.

He came and he pulled out a mattress that he had there. He pulled it out and said, "You can sleep here." Then he gave us two sheets. We ate and talked awhile about the experience we had just had. We spoke about the helicopter and all that, about the walking, because we walked a lot. And we thanked God for getting us across uneventfully.

The Honduran guy had already been here six months. He had been living in the apartment, waiting for the right moment to try to pass through the Border Patrol checkpoint on the way to Houston. They were waiting for a rainy day because immigration doesn't go out much when it rains.

After an hour, at maybe 12 a.m., we said, “OK, we're going to sleep because it's time to rest. We've had a rough day."

The Honduran had his own bed and we had a mattress for the two of us. I laid down on the mattress and gave thanks to God for getting us across safely.

I was thankful because there are many people who don't cross the river.

Many people get left behind in the desert. And there are many people who are caught crossing the river. We were lucky to have gotten this far. And we had already gotten through the hardest part.

And from there, we went to sleep. We slept until 9 a.m. the next day and then had breakfast. After a little while, he told us, "Let's go to the shop." The mechanic's shop was only a few blocks away. They didn't want us to stay there alone in the room with nothing to do.

So we walked to the shop to get a change of scenery.

In the shop, we found ways to pass the time. We got to check on some cars and take a few things apart. I don't normally work on cars, but I was watching. There were three mechanics, so we could go with any of those three. If we had any questions about cars, we could ask them. It helped us pass the time more quickly.

A selfie José Miguel took of himself during his time in McAllen. Photo by José Miguel Cáceres, used with permission.

The boss of the operation — who was supposed to help get us to Houston — he was the head of the shop. He had other people who were going to take us to Houston. The shop was big, but he didn't have his own house, just the apartment. He was American, but his mother and father were Honduran and he was born here.

We stayed there until 4 p.m., more or less. When we walked home, the neighborhood was calm. There wasn't traffic and there weren't any people walking around. The street was nice and quiet and there weren't any problems.

Editor's note

I spoke with José Miguel in July at his family's apartment in Arlington, Virginia, where he told me about his first day in the U.S., as well as what came afterward.

He spent five days at the safe house in McAllen while smugglers waited for the right moment to circumvent a Border Patrol checkpoint on the road to Houston. The attempt failed, however, and he was apprehended with 10 other migrants.

He was detained by federal immigration authorities for nearly four months, with most of the time spent at a detention center in Louisiana, far from his family. He was released on bond in mid-July and currently hopes to receive asylum in the U.S.

This is just one story. According to U.S. Customs and Border Protection, from Oct. 1, 2014, to July 31, 2015, Border Patrol agents made 270,818 apprehensions on the Southwest border — numbers that are lower than last year, but still significant. Many of these people were fleeing violence, poverty, and persecution. Others hoped to reunite with relatives on the other side.

Share this story and help more people understand the reality at the border.

*This text has been edited for narrative flow, grammar, and clarity.

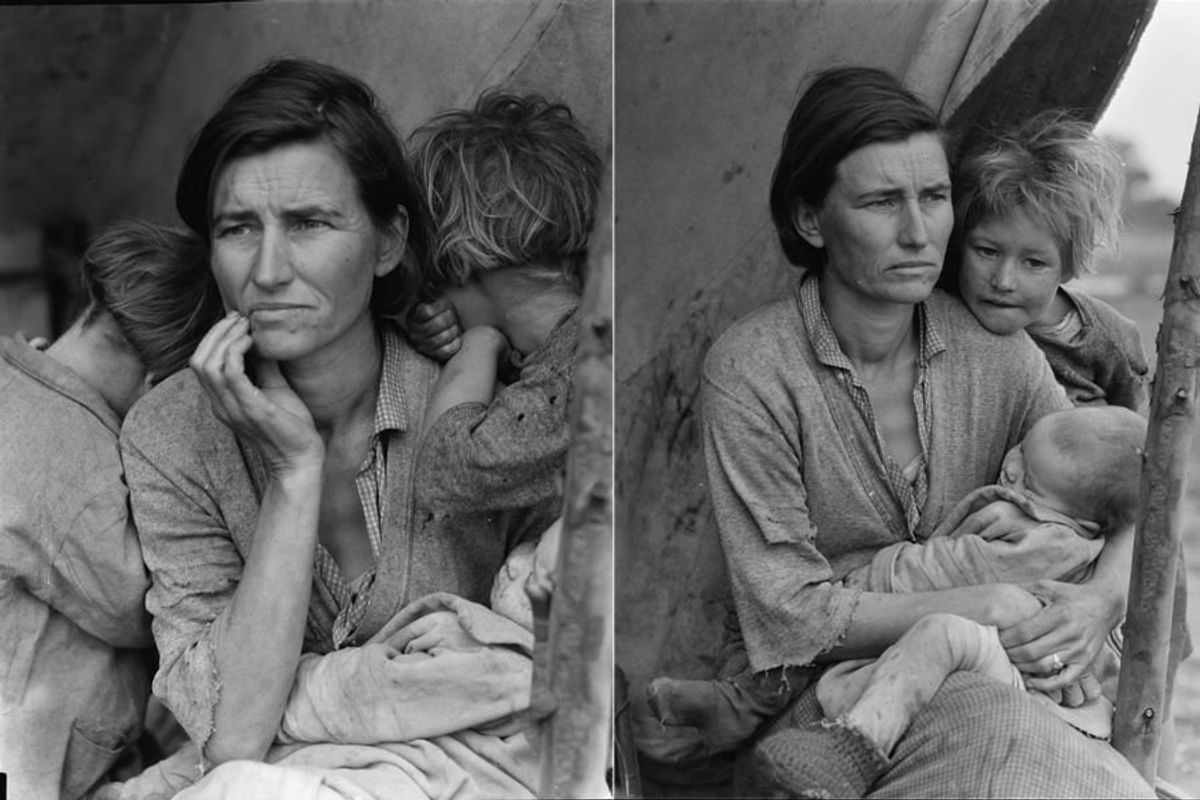

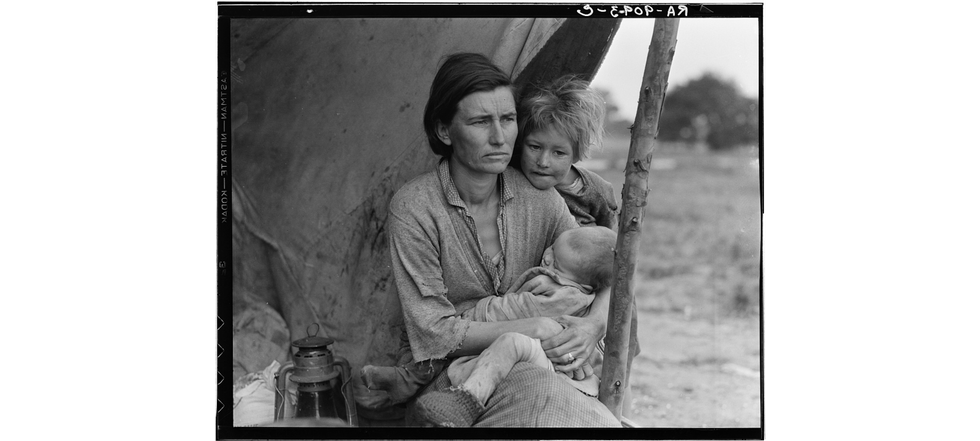

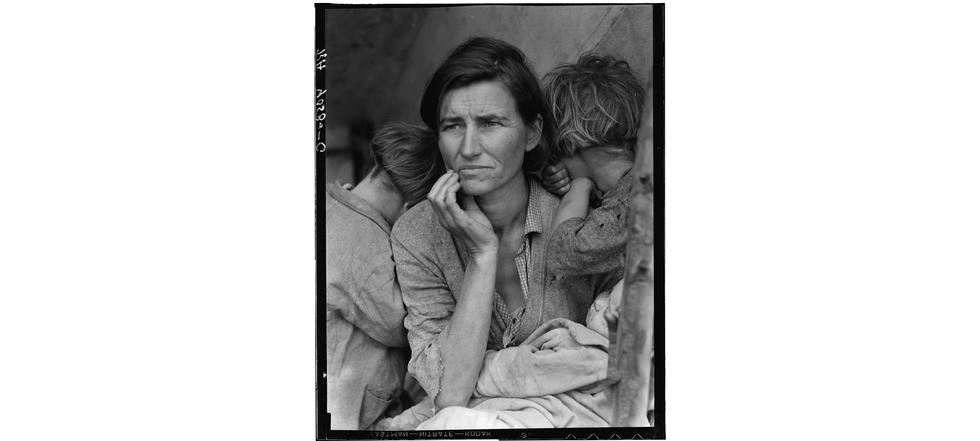

Worried mother and children during the Great Depression era. Photo by Dorthea Lange via Library of Congress

Worried mother and children during the Great Depression era. Photo by Dorthea Lange via Library of Congress  A mother reflects with her children during the Great Depression. Photo by Dorthea Lange via Library of Congress

A mother reflects with her children during the Great Depression. Photo by Dorthea Lange via Library of Congress  Families on the move suffered enormous hardships during The Great Depression.Photo by Dorthea Lange via Library of Congress

Families on the move suffered enormous hardships during The Great Depression.Photo by Dorthea Lange via Library of Congress

Millennial mom struggles to organize her son's room.Image via Canva/fotostorm

Millennial mom struggles to organize her son's room.Image via Canva/fotostorm Boomer grandparents have a video call with grandkids.Image via Canva/Tima Miroshnichenko

Boomer grandparents have a video call with grandkids.Image via Canva/Tima Miroshnichenko

kenan and kel nicksplat GIF

kenan and kel nicksplat GIF  season 6 GIF

season 6 GIF

Vintage portraits of a woman and two children, showcasing elegant attire of their era.

Vintage portraits of a woman and two children, showcasing elegant attire of their era. Three friends enjoy a lively music session indoors.

Three friends enjoy a lively music session indoors.