This year's election and its aftermath made one thing clear: There are multiple Americas and we're not listening to each other.

It's not necessarily our fault either. Search engines and social media platforms like Google and Facebook have been accused of creating "filter bubbles" for users, using algorithms to determine what we see based on what they think we want to see, often excluding information that might challenge our pre-existing beliefs or make us feel uncomfortable.

Since the presidential campaign kicked off last year, the filter bubble has been the subject of fierce discussion, credited with (or blamed for) everything from the surprise of Donald Trump's victory to the proliferation of fake news to the eroding of democracy.

Here at Upworthy, the "filter bubble" has long been kind of a big deal. Our co-founder and CEO Eli Pariser coined the term in his book "The Filter Bubble" way back in 2011, before anyone could imagine the events of 2016.

Photo by Jess Blank/Upworthy.

I sat down with Pariser (full disclosure: my boss' boss) to ask him how our online filters shape our lives and ideas — and how we as individuals can break through and reach out to the other side.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Q: What is the filter bubble?

Pariser: The filter bubble is the personalized universe of information that we increasingly live in online. Websites know who we are, and they tailor their content to what they think we want to see. And when you add all of that up, you get your own personal filter bubble.

We don’t always know or see that this filtering is being done for us, and we don’t see what’s being filtered out. And so, without knowing it, we can see a view of the world that we think is representative, but is actually just showing us what these websites think we want to see.

How do sites like Facebook and Google build these bubbles?

By algorithms that are collecting personal data about you, making some guesses about what you might be interested in, and showing you some stories and not others. And in some cases, sharing that information with other websites across the web.

"It’s always tempting to just write off people who disagree with you. I think it’s really important to at least understand how they could come to believe what they believe." — Eli Pariser

Some of it's very crude: I’m a man, not a woman. I’m white, I’m not Latino or black. So some of it is very basic demographic level. Some of it is much more sophisticated. It’s looking at the whole history of what I’ve clicked on over the course of my time online and trying to make some assumptions about what it means I will click on going forward.

Give me an example of how this works.

One of the craziest filter bubble experiences I’ve ever had was on a radio show, where the host was asking people to google "Barack Obama" and call in and tell him what they saw. And the first three people who called in all saw the exact same thing, which was the Wikipedia entry on Barack Obama and the White House. And I was thinking, "This is the worst radio interview ever because everyone’s seeing the same thing."

And then a guy called in and said, "My first result is about how Obama’s birth certificate is fake." And that’s the kind of thing that’s really unnerving because he didn’t know that his results were different from everyone else’s until he heard what their results were, and in fact, for some reason, Google thought he would be interested in this totally untrue story about Obama.

But why should I want to be bombarded with viewpoints I disagree with in my social media feed? I'd rather not deal with those people, to be honest.

It’s always tempting to just write off people who disagree with you. I think it’s really important to at least understand how they could come to believe what they believe. Because even if you don’t agree, understanding the framework in which they’re operating opens up the door to persuasion and to an actual conversation.

What can I do if I want to get outside my filter bubble?

I’d say there’s a few things you can do. The first is to seek out what Ethan Zuckerman calls “bridge figures,” people who kind of have a foot in several different communities. And they can act as a kind of interpreter and help people. It’s hard to plunge right into a group of people who you deeply disagree with, so finding the bridge people who can interpret and explain how that group of people is seeing the world is often really important.

The second piece is just seeking out more diverse sources of information, and actually, if it’s on Twitter or on Facebook, finding some people who you really disagree with to add to your feed and follow and engage with is a great way to get outside of your bubble.

"You can stay inside your bubble but that's your choice. But the thing is, just because you choose to believe certain things are true doesn’t mean that’s actually what’s true." — Eli Pariser

And then I think the third piece is to really understand which mediums are good for which things because Facebook is going to organize information in one way, and Twitter is going to organize information in another way, and we shouldn’t assume that all of them are great for the same kind of purposes. Twitter, generally, makes it easier to view content from people you might deeply disagree with than Facebook does. You can decide to spend more of your time on a platform like that.

We just had a really tense, brutal election. It seems like a lot of people are finding it hard to talk to the other side right now. What advice do you have for them?

The thing that Clinton and Trump supporters can do that’s actually important is engage in places where there are other identities that are the most important. So, sports, for example, is a place where people are willing to put aside their partisan identities because we’re all fans of this one team. And actually, what researchers have said is that those sports forums are some of the places where the best cross-partisan dialogue is actually happening because it’s all cool. Because we all love the Patriots best, and so we can argue about race, and we can argue about these other things, and it’s OK. And I think finding those spaces where there’s an identity that supersedes our partisan identity is one of the best ways to engage with people very unlike us.

What advice do you have for people who would just rather stay inside their comfort zone than deal with all that?

You can stay inside your bubble, but that's your choice. But the thing is, just because you choose to believe certain things are true doesn’t mean that’s actually what’s true. And we can lose sight of the real problems and the real challenges in the world, but they don’t lose sight of us. I think, at some point, reality comes to bare, and that’s what we are seeing in this election.

There are things that are real in the world that no amount of telling yourself they’re not true helps solve. You have to grapple with those actual issues.

How do you approach those difficult disagreements, either in real life or on social media?

I would say, have conversations in which you affirm the other person. Because research shows that when you can remind people what’s good about themselves, they’re much more open and they’re much more open to consider other ideas.

Courtesy of Kerry Hyde

Courtesy of Kerry Hyde Courtesy of Kerry Hyde

Courtesy of Kerry Hyde Courtesy of Kerry Hyde

Courtesy of Kerry Hyde Courtesy of Kerry Hyde

Courtesy of Kerry Hyde Mama Said Love GIF by Originals

Mama Said Love GIF by Originals hallmark hall of fame mother daughter GIF by Hallmark Channel

hallmark hall of fame mother daughter GIF by Hallmark Channel you're safe here season 4 GIF by Portlandia

you're safe here season 4 GIF by Portlandia Busy Philipps Tonight GIF by E!

Busy Philipps Tonight GIF by E! GIF by Better Things

GIF by Better Things A newborn baby with her Teddy bear. (Representative image)via

A newborn baby with her Teddy bear. (Representative image)via  Disney made magic happen in the 90s.

Disney made magic happen in the 90s.  Turns out, the film was in shambles.

Turns out, the film was in shambles. It wasn't really a pitch, like the movie ended up being, it was funny.

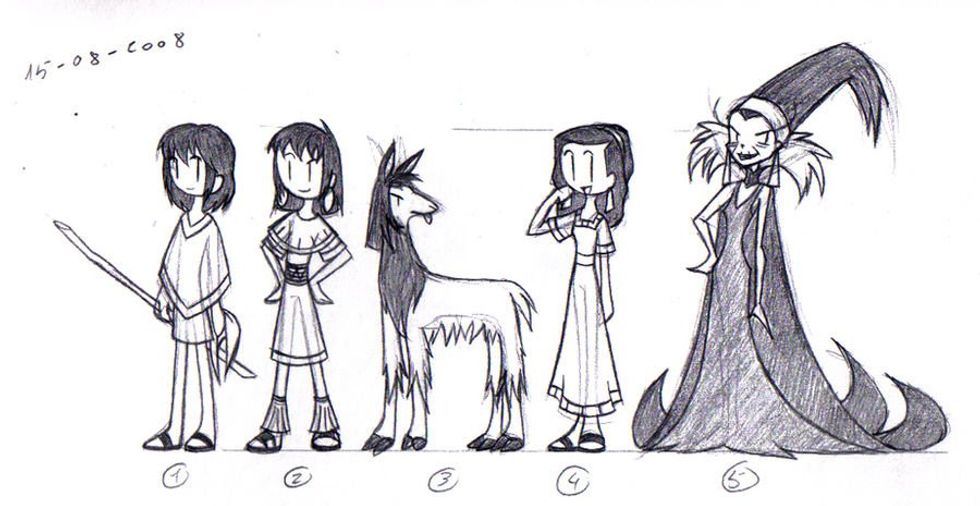

It wasn't really a pitch, like the movie ended up being, it was funny. Sketches from Kingdom of the Sun

Sketches from Kingdom of the Sun

Season 10 Episode 3 GIF by Friends

Season 10 Episode 3 GIF by Friends

Some people would prefer to just not be tan than not fully clean themselves.

Some people would prefer to just not be tan than not fully clean themselves.