Giving a patient bad news can be uncomfortable, but med student Katie Goldrath had no choice.

Nobody likes to deliver bad news, but this was important. The patient, a young woman named Robin, had come in because she kept getting nosebleeds — and Goldrath had just learned the reason behind it was leukemia.

Goldrath knew Robin needed to get into treatment as soon as possible. She also knew if their conversation went poorly, Robin might get angry or even storm out, delaying her treatment ... and possibly endangering her life.

Luckily, if things spiraled out of control, Goldrath could always hit the redo button. That's because Robin wasn't a real person. Robin was part of a computer program called MPathic-VR, designed to help young doctors learn to communicate with their patients.

Robin. Image courtesy of Dr. Fred Kron/Medical Cyberworlds, Inc.

Goldrath's experience talking to Robin was part of a study to test out the program's potential.

A doctor’s words can change a person's life, but knowing what to say, and how to say it, isn't easy. It's a serious skill that has to be learned and mastered. Better communication can make patients feel better, both emotionally and physically. Poor communication, on the other hand, can lead to malpractice suits, patients not listening to their doctors, and sicker people.

Medical students like Goldrath usually go through special training to learn these skills. Common methods include multimedia trainings or holding mock conversations with students or actors standing in for the patient. But these can have downsides. The mock conversations can be expensive and hit or miss depending on how good the "patient’s" acting skills are. The "patient" might also not be able to give very detailed feedback.

A program like Robin's simulation might solve some of these common communication problems.

Motion capture was used to help produce Robin's range of facial expressions. Image courtesy of Dr. Fred Kron/Medical Cyberworlds, Inc.

Though talking to a computer might seem weird at first, Robin is designed to react as much like a real human as possible. She has her own expressions, mannerisms, and emotions. The software can also recognize what the student is saying and use a camera to track the student's body language. Even small eye movements don't go unnoticed.

"It was actually pretty incredible to see what it could pick up on," Goldrath said of her conversations with Robin. Did Goldrath lean in and look Robin in the eye, a welcoming, compassionate gesture, or did she act aloof and look away? The computer could record her body language and posture and provide feedback for the next time around.

The program also comes with two other scenarios for doctors to practice with: one that focuses on navigating family drama and another that involves talking one-on-one with a nurse who’s upset she’s been left out of previous conversations.

Doctors care about their patients. This tool can help them ensure their patients know that.

In the end, the study found that, compared to standard multimedia training, MPathic-VR students improved more and felt more positive about the experience. Their results were released in the April issue of Patient Education and Counseling.

While MPathic-VR isn't in any schools yet, Dr. Fred Kron, founder of the company who made the program, says they're starting to look at rolling out the software and want to continue Robin's story.

Everyone wants to be able to express empathy, but it can be hard, especially when delivering upsetting information in a high-stress and fast-paced environment. There's no perfect recipe for how to give bad news, but these kinds of tools might help people who find themselves doing so frequently to find their footing or even just hone that skill with compassion.

A father does his daughter's hair

A father does his daughter's hair A father plays chess with his daughter

A father plays chess with his daughter A dad hula hoops with his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad hula hoops with his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. A dad talks to his daughter while working at his deskAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad talks to his daughter while working at his deskAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. A dad performs a puppet show for his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad performs a puppet show for his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. A dad walks with his daughter on his backAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad walks with his daughter on his backAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. a dad carries a suitcase that his daughter holds onto

a dad carries a suitcase that his daughter holds onto A dad holds his sleeping daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad holds his sleeping daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. A superhero dad looks over his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A superhero dad looks over his daughterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. A dad takes the small corner of the bed with his dauthterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission.

A dad takes the small corner of the bed with his dauthterAll illustrations are provided by Soosh and used with permission. Season 8 Nbc GIF by The Office

Season 8 Nbc GIF by The Office Figuring out our finances may be getting easier.

Photo by

Figuring out our finances may be getting easier.

Photo by  Plumbing Plumber GIF by Family Guy

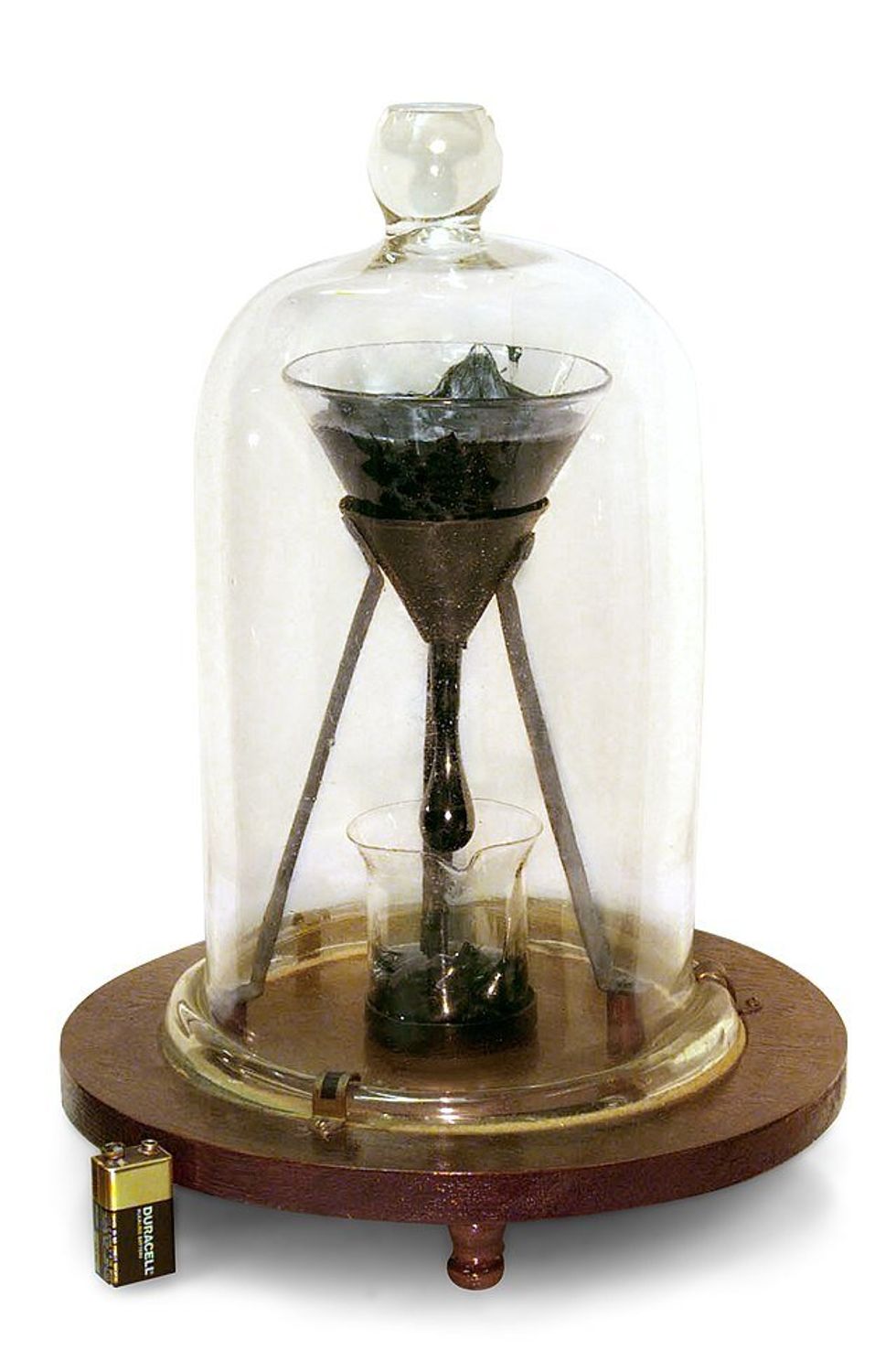

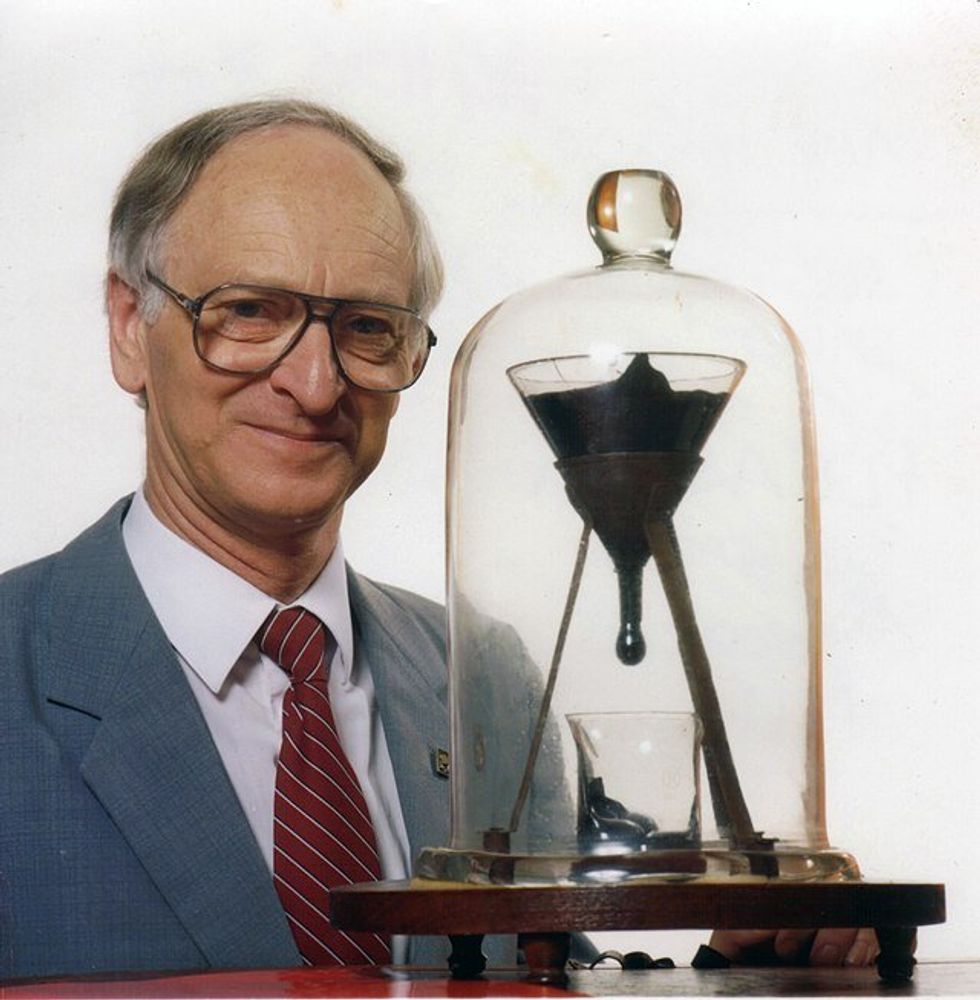

Plumbing Plumber GIF by Family Guy Pitch moves so slowly it can't be seen to be moving with the naked eye until it prepares to drop. Battery for size reference.

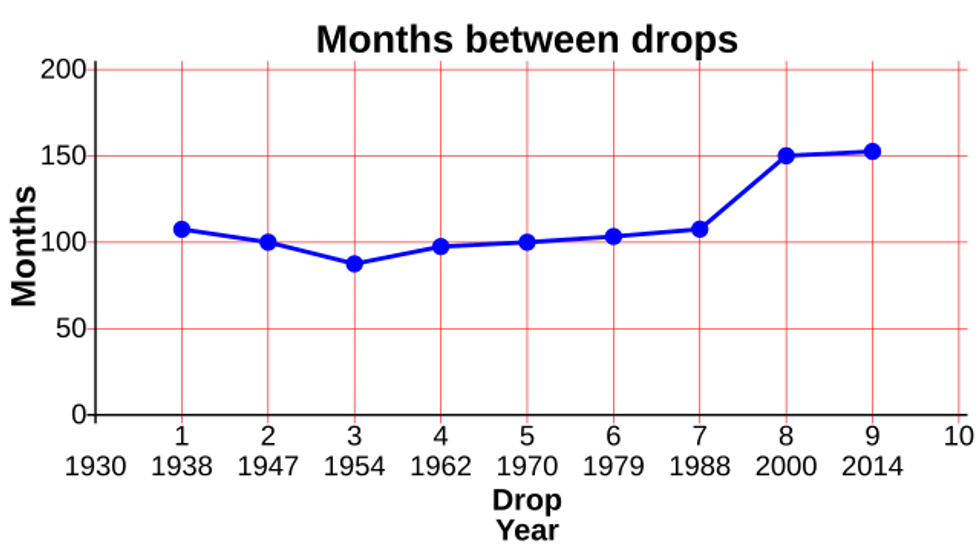

Pitch moves so slowly it can't be seen to be moving with the naked eye until it prepares to drop. Battery for size reference. The first seven drops fell around 8 years apart. Then the building got air conditioning and the intervals changed to around 13 years.

The first seven drops fell around 8 years apart. Then the building got air conditioning and the intervals changed to around 13 years. John Mainstone, the second custodian of the Pitch Drop Experiment, with the funnel in 1990.

John Mainstone, the second custodian of the Pitch Drop Experiment, with the funnel in 1990. The Alhambra sits atop a plateau overlooking Granada, Spain.

The Alhambra sits atop a plateau overlooking Granada, Spain. Fountain of the Lions at the Alhambra, Granada

Fountain of the Lions at the Alhambra, Granada Remains of baths inside the Alhambra Alcazaba

Remains of baths inside the Alhambra Alcazaba