The epic true tale of the vigilante librarian who saved thousands of books from jihadists.

Under the dark cover of night, a team of clandestine agents smuggled contraband on mule carts past the heavily armed militants who policed the ancient streets of Timbuktu...

But this undertaking was a little less "Ocean's Eleven," a little more "Indiana Jones" with an Islamic bent — because the traffickers were librarians, and their black market swag was a vast collection of hundreds of thousands of historical manuscripts dating as far back as the 11th century.

Photo by Francois Xavier Marit/AFP/Getty Images.

The mastermind behind this grand scheme? A middle-aged book collector named Abdel Kader Haidara.

Haidara spent most of his life searching his native Mali and other parts of Western Africa for lost relics from the region's rich history. Over the years, he had amassed thousands of rare and valuable manuscripts, which he preserved, restored, and digitized for future generations.

Haidara's collection included historical chronicles of the rise and fall of Saharan and Sudanese monarchs; ethical quandaries by Islamic philosophers debating everything from polygamy to smoking tobacco; medical volumes full of treatments derived from birds, lizards, or plants; codices hand-bound in lavish materials such as goatskin or fish scale and adorned with glittering gold calligraphy; rare illustrated copies of the Quran itself; and ancient secular writings on astronomy, poetry, and math.

"A lot of people were surprised because they had been told — even at school — that there were no written African historical records," Haidara said in 2014. "But we have hundreds of thousands of these documents in Arabic and in African languages."

Photo by Fred DuFour/AFP/Getty Images.

When the Mali crisis began in May 2012, Haidara quickly realized that Timbuktu's incredible archives were in danger.

An alliance of militant Tuareg rebels and al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQMI) seized a number of northern Malian territories, including Timbuktu. They overthrew the country's president, Amadou Toumani Touré, and imposed Sharia in the now-independent territory of Azawad, banishing anything that fell outside their narrow interpretation of the Quran.

Soon they were demolishing Sufi mausoleums and other Islamic traditions that opposed their own zealotry. Haidara knew it was only a matter of time before they came for the book collections, too.

"The manuscripts show that Islam is a religion of tolerance," he told National Geographic. Haidara believed that the archives could not only change Western perceptions of Islam, but could also refute jihadist dogma — something which the extremists would never allow.

Photo by Fred DuFour/AFP/Getty Images.

Days after the invasion, Haidara called together his colleagues from the Timbuktu library association, who represented 45 different Malian libraries and about 400,000 rare volumes.

As he recalled in the Wall Street Journal, he told the assembled group: “I think we need to take out the manuscripts from the big buildings and disperse them around the city to family houses. We don’t want them finding the collections of manuscripts and stealing them or destroying them.”

With help from family, tour guides, and other archivists, Haidara and his team began buying all of the metal and wooden trunks they could find without arising suspicion. Once they'd bought up all the stock in Timbuktu, they sent their buyers to other markets south of the city, or purchased unused oil drums and barrels to convert for their purposes.

Photo by Eric Feferberg/AFP/Getty Images.

They stored the crates at Mamma Haidara and other libraries throughout the city, where small groups of volunteers would gather at night to carefully pack the delicate manuscripts inside. They worked entirely by flashlight, since the jihadists had cut their access to electricity.

Once the books were packed, they were smuggled by mule carts at night to hiding places under the homes of volunteers across the city.

Photo by Pascal Guyot/AFP/Getty Images.

Within a few months, there were nearly 2,500 footlockers full of manuscripts hidden throughout the city. But moving them out of al-Qaeda territory wouldn't be easy.

Donations began to pour in from Indiegogo and private foundations to help fund strategic smuggling trips by river and by road, moving manuscripts incrementally in order to cut down on potential losses.

But they still had to contend with both extremist border patrols and the Malian army, which was on the lookout for smuggled weapons en route to or from al-Qaeda. Even the French military, which had arrived to help liberate Timbuktu, formed another inadvertent obstacle when it almost fired on a boat full of books, acting under the assumption that they were trafficking firearms.

Photo by Kenzo Tribouillard/AFp/Getty Images.

The operation lasted for nine harrowing months, during which the radicals managed to destroy only 4,000 manuscripts.

Of course, there were plenty of close calls along the way.

Early in the campaign, militant leaders stopped Haidara's nephew, Mohammed Touré, as he was leaving the library late one night with a trunkful of manuscripts. They arrested him for stealing and threatened to cut off his hands. But Haidara swung into action and told the Islamist police that Touré was a legal employee of the museum who was doing his job by taking the books to be repaired.

On another occasion, a fleet of boats carrying 300 footlockers full of books was held hostage by opportunistic hijackers until Haidara could pay the ransom they demanded.

“If we hadn’t acted, I’m almost 100% certain that many, many others would have been burned," Haidara told the Wall Street Journal.

Photo by Evan Schneider/Stringer/Getty Images.

The remaining manuscripts are now safe in climate-controlled storage in Bamako. But they can't stay there forever.

Between the humidity in the Malian capital and the creaking weight of tall stacks of boxes upon boxes threatening to crush the books beneath them, it's only a temporary haven. The Malian government has estimated that it would cost nearly $11 million to build new archives in the capital to properly preserve and restore the codices.

As for Haidara, he received the 2014 Africa Prize from Germany and is the subject of a new book called (appropriately) "The Bad-Ass Librarians of Timbuktu." But he's still more concerned about the collection.

"I'm all the time surrounded by worry, by responsibility, sometimes I even forget my family," he told National Geographic."My only ambition is to rehabilitate all these libraries in Timbuktu, so that I can bring all the manuscripts back to each family that entrusted them to me. That will give me a little bit of peace."

Patagona has always done a great job taking care of its employeesYukiko Matsuoka/Flickr

Patagona has always done a great job taking care of its employeesYukiko Matsuoka/Flickr While nursing my baby during a morning meeting the other day after a…

While nursing my baby during a morning meeting the other day after a… Not sure if Dwight Schrute would be as accomodating.

Not sure if Dwight Schrute would be as accomodating. "Washington Crossing the Delaware" by George Caleb BinghamPublic domain

"Washington Crossing the Delaware" by George Caleb BinghamPublic domain Kenan Thompson Snl GIF by Saturday Night Live

Kenan Thompson Snl GIF by Saturday Night Live Jake Johnson Fox GIF by New Girl

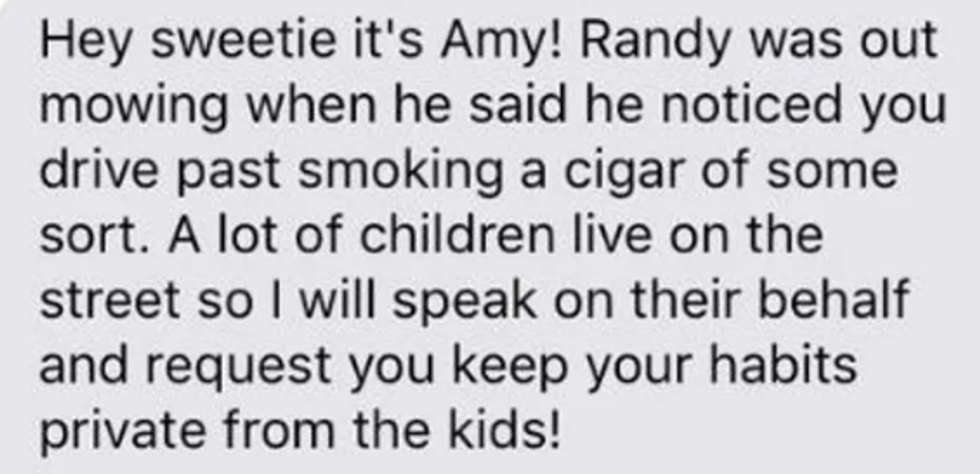

Jake Johnson Fox GIF by New Girl A text sent to Sarah Holder.via

A text sent to Sarah Holder.via  Sarah Holder showing a half-eaten taquito.via

Sarah Holder showing a half-eaten taquito.via  This really shouldn't make us uncomfortable, no matter how much skin is showing.

Photo by

This really shouldn't make us uncomfortable, no matter how much skin is showing.

Photo by  via bfmamatalk / Facebook

via bfmamatalk / Facebook

It's completely backwards that male nipple is acceptable in public, but not a breastfeeding mother's

It's completely backwards that male nipple is acceptable in public, but not a breastfeeding mother's