The black soldiers who biked 2,000 miles over the mountains and out of American history.

If you don't know, now you know.

As the sun set on their first day, the men of the 25th Infantry Bicycle Corps were cold, tired, and soaking wet. And they still had nearly 1,900 miles to go.

It was summer 1896. The 20 members of the 25th Infantry, an all-black company out of Fort Missoula, Montana, had been volunteered by their white commanding officer, 2nd Lt. James Moss, to study the feasibility of using bicycles in the military, which, unlike horses, required no food, water, or rest.

Moss was allowed to lead his men on a near-2,000-mile journey from Missoula to St. Louis, Missouri. The weather was punishing, the ride grueling, and the water poisonous. The men of the 25th were selected for the experiment, frankly, because as soldiers, they were worth little to the U.S. military.

Image via The Montana Experience: Stories from Big Sky Country/YouTube.

But odds are you haven't heard of the 25th Infantry Bicycle Corps. Their story was quickly forgotten, barely earning a mention in the pages of history books.

But in reality, these men were unsung heroes. Don't believe me? Here are nine reasons why.

1. Before the journey, many of the men didn't even know how to ride a bike.

Only five of the 20 soldiers were experienced bicycle riders ahead of the cross-country trek. One learned how to ride just a week prior. At the time, safety bicycles (the new model with two wheels of the same size as opposed to the large wheel on the front) were relatively new and exciting.

Photo of Pvt. John Findley, one of the few men in the company with any cycling experience. Image via The Montana Experience: Stories from Big Sky Country/YouTube.

2. The bicycles selected for the journey were on loan and extremely clunky.

The Spalding company donated bicycles for the experiment. The bikes had steel rims and no gears (those hadn't been invented yet). Each bicycle weighed in at 59 pounds, without gear. A heavy one-speed bike is just fine on a breezy ride through the country. But these men were traveling over mountains.

Are your legs tired yet?

Image via The Montana Experience: Stories from Big Sky Country/YouTube.

3. You know when your grandparents say they had to walk uphill both ways? This was the journey for the 25th. Only true.

The route to St. Louis was selected because the men would encounter diverse terrain — perfect for a test of military feasibility. The company traveled from the steep slopes of Montana through the dry, sandy roads of Nebraska. They encountered snow, rocks, mud, and punishing winds. They even crossed the rivers on foot, multiple times, holding their bikes over their heads.

"We were wet, cold and hungry, and a more jaded set of men never existed," wrote Edward Boos, a correspondent for the Daily Missoulian and an avid bicyclist who traveled with the 25th to report on their experiences.

Why didn't they just ride on the road? Good question.

The 25th riding past Old Faithful at Yellowstone. Image via The Montana Experience: Stories from Big Sky Country/YouTube.

4. The roads were so bad, the men often resorted to riding on train tracks.

The roads that existed at the time were worn down from wagon wheels creating deep rutted paths. And when it rained, they were washed away, replaced with thick mud. Instead, at times the men rode their bikes on the train tracks, which weren't much better considering there was nothing between the railroad ties but deep holes. The men held tight to their handlebars to keep from flipping over, resulting in hand numbness and intense shoulder pain for miles.

And you thought you were sore after a 50-minute spin class.

Image via The Montana Experience: Stories from Big Sky Country/YouTube.

5. Each soldier carried 55 pounds of gear on his bike.

Their supplies included half a tent, a bedroll, a pair of underwear, an undershirt, socks a toothbrush, two days worth of food (burnt bread, beans, bacon or canned beef, and coffee), various tools, and a rifle. Every 100 miles or so, the men would stop at posts to refill their supplies.

The supplies were kept in white rolls on the handlebars and in small custom leather or metal pouches attached to the bicycle frame. U.S. National Archives and Records Administration/Wikimedia Commons.

6. They barely got any rest, and at times when they did, it was amid cacti.

The men rode 35 full days of the 41-day journey. Considering the terrain, there weren't many good places to stop and rest. They often made camp in fields of prickly pear cactus, though few men reported being poked.

Image via The Montana Experience: Stories from Big Sky Country/YouTube.

7. And, oh yeah, the water was poisonous.

Because a 2,000-mile journey on a one-speed bike isn't tricky enough, once the soldiers got to Nebraska, they were drinking from water that had dangerously high levels of alkali and even cholera.

Vapors from the dusty terrain made the men sick, too. 2nd Lt. Moss even began to hallucinate.

Image via The Montana Experience: Stories from Big Sky Country/YouTube.

8. Because they were black, the 25th were often considered second-rate soldiers, but they were anything but.

The 25th Infantry were one of four all-black infantry regiments created by Congress after the Civil War. The army moved the unit out west to help tame the wild frontier, where they picked up the name "Buffalo Soldiers" from the Cheyenne.

The men were given slow horses, rotten food, and shoddy gear for the task. Despite the miserable treatment and conditions, though, black companies had some of the lowest desertion rates of regiments out west. And between 1870 and 1898, 23 black soldiers were awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor.

Image via The Montana Experience: Stories from Big Sky Country/YouTube.

9. But when they reached St. Louis, the men received a warm welcome from the city's people.

2nd Lt. Moss and the 25th were escorted to a hotel just outside of town by a local bicycle club. Later, they performed maneuvers in a St. Louis parade, where 10,000 people came to cheer for them. Sadly, not a single military officer was there to greet them.

Image via The Montana Experience: Stories from Big Sky Country/YouTube.

The men had done it — traveling 1,900 miles in 41 days across some of the country's most punishing terrain. Moss wanted to continue the trip and travel to St. Paul, Minnesota. But he was told to return the bikes and send his men back to Montana on the train.

Despite a successful journey, the experiment was over.

The story of the 25th Infantry Bicycle Corps is one of those unique, surprising moments in U.S. history.

After the journey Boos wrote, "This hard work was too much. It could not prove anything about a bicycle and was merely a test of physical endurance of which we had quite sufficient."

120 years later, this story is about so much more than a bicycle. It's about adventure, guts, and mental and physical fortitude. Other than the all-black cast, it has all the makings of a big-budget Hollywood movie. (I kid, I kid.)

Image via The Montana Experience: Stories from Big Sky Country/YouTube.

Christopher Plummer and Julie Andrews on location in Salzburg, 1964

Christopher Plummer and Julie Andrews on location in Salzburg, 1964 Car Drifting GIF

Car Drifting GIF Bed Bugs Belarus GIF

Bed Bugs Belarus GIF Bed bugs are about the size of an apple seed.

Bed bugs are about the size of an apple seed. bug GIF

bug GIF Checking mattresses for signs of bed bugs at a hotel can help you avoid bringing them home.

Checking mattresses for signs of bed bugs at a hotel can help you avoid bringing them home.

A person holds a plate with bulletsImages via Canva

A person holds a plate with bulletsImages via Canva A horse making a funny faceImage via Canva

A horse making a funny faceImage via Canva A baby with glasses sleeping on a moon pillowImage via Canva

A baby with glasses sleeping on a moon pillowImage via Canva Ocean Seafood GIF by Lorraine Nam

Ocean Seafood GIF by Lorraine Nam Giga Pudding Snack GIF

Giga Pudding Snack GIF

A young boy blows a whistle Image via Canva

A young boy blows a whistle Image via Canva Two women laugh looking at a laptop screenImage via Canva

Two women laugh looking at a laptop screenImage via Canva

Two women at a gym push an oversized envelopeImages via Canva

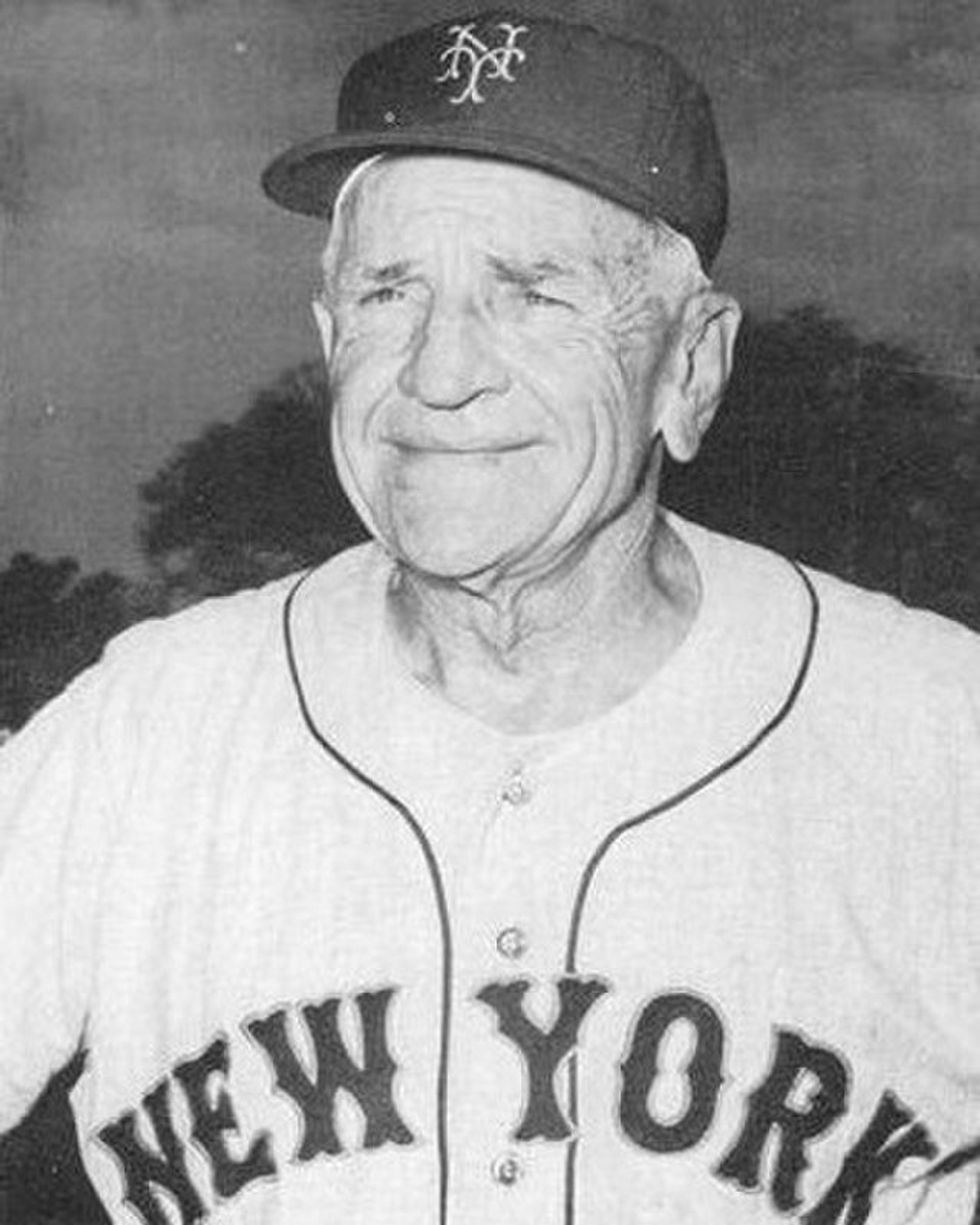

Two women at a gym push an oversized envelopeImages via Canva Casey Stengel served as inspiration for the Miracle Max character in "The Princess Bride."Public Domain

Casey Stengel served as inspiration for the Miracle Max character in "The Princess Bride."Public Domain