The 9 teachers who just received awards from the White House were all in the U.S. illegally.

A work permit can change your life.

Jaime Ballesteros first realized just how much his immigration status mattered when he started looking at colleges.

He didn't have a Social Security number — and without that, he wouldn't be able to apply for schools alongside his peers, who were considering colleges like Harvard and Yale.

He knew what was wrong. Born in the Philippines, Jaime came to the U.S. with his parents and older brother when he was 11 years old. His father had a temporary work visa tied to his job as an accountant, which allowed him to bring his wife and children with him.

Jaime at roughly age 6 in Bacolod City, where his family lived in the Philippines. Photo courtesy of Jaime Ballesteros.

Then the recession hit. Jaime's father lost his job in 2007, which meant their visas would expire.

His family went from living the American Dream to immigration fugitives in the course of a year.

The timing couldn't have been worse, either. Jaime was looking at colleges and didn't know how to handle questions about citizenship and legal residency. He turned to one of the few people he thought he could trust, Ms. Solberg, his English teacher.

“She was the first person I came out to as an undocumented person," he told Upworthy. “I was very afraid of putting my family in harm's way."

During his time at Drew University, in December 2011. Photo courtesy of Jaime Ballesteros.

She helped him apply to college, a decision that set him on the path for success. The biggest impediment was money — as an undocumented immigrant, he wasn't eligible for federal financial aid and loans. But after struggling through several applications, he connected with an admissions counselor at Drew University, a liberal arts college in New Jersey. The school was able to offer enough in scholarships to cover his tuition.

He also got a boost from a new immigration policy rolled out in 2012, during his junior year at Drew. The Obama administration announced a program that would allow young undocumented immigrants like him to live and work in the U.S. legally. He applied and was approved.

But he never forgot the support he received from Ms. Solberg.

When Jaime graduated college, he joined Teach for America. Now he's a high school chemistry teacher in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles.

At the Ánimo College Preparatory Academy, where he teaches chemistry. Photo courtesy of Jaime Ballesteros.

On the first day of class, he told his students — many of them immigrants, as well — that he was undocumented. “I want them to be comfortable approaching me," he said.

Stories like Jaime's are becoming more and more common.

The program that gave Jaime a pathway to become a teacher — Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) — has allowed more than 664,000 people to work legally in the U.S.

Teachers make up a portion of those newly employed young people, a fact recognized by the White House last week when it handed out Champions of Change awards to nine young teachers, all of whom have work authorization through DACA.

The nine teachers awarded Champions of Change awards by the White House. Photo courtesy of The White House.

The awards typically go to innovative American workers across the spectrum. This time around, all of the recipients were people who either overstayed a visa or entered the country illegally.

Now they're able to live in the U.S. without fear of imminent deportation.

Congrats to Jaime and the eight other educators honored by the White House this week:

1. Kasfia Islam, who moved from Bangladesh to a small town in Texas with her parents at age 6.

Photo courtesy of Kasfia Islam.

As a pre-kindergarten teacher, she said she's careful to watch for students who are learning English and might not understand.

“[The students] want to communicate so badly with you, but they don't have the means to do it, so it can be frustrating for them," she said.

2. Marissa Molina, who came to the U.S. from the Mexican state of Chihuahua when she was 9 years old.

Photo courtesy of Marissa Molina.

After years of hiding her immigration status, Molina feels validated to be able to accept an award from the White House and speak publicly about her situation — for herself and others like her.

“I feel really overwhelmed with emotion," she said about the award. "For many years, I was made to believe that people like me didn't belong in these spaces."

3. Luis Juarez Trevino, whose family brought him to Texas as a child, seeking a better life.

Photo courtesy of Luis Juarez Trevino.

As an immigrant student without much money, Trevino saw college and a professional career as a long shot. “The odds were against me," he said in an email.

“Teachers truly took the time to motivate me, care for my wellbeing, and push me outside of my comfort zone."

4. David Liendo Uriona, who came to the U.S. from Bolivia for a karate tournament and never returned.

Photo courtesy of David Liendo Uriona.

Uriona didn't think college would be an option for him, since he had been living in the U.S. without legal status since he was 14.

“When I was in high school, I felt dejected as result of my lack of documentation," he said. “I know from firsthand experience that there are many students that felt like me in high school, and teaching them that their dreams can come true is one of my biggest motivations."

5. Maria Dominguez, who came to the U.S. when she was 9, after her father — who was living in Texas as a legal resident — passed away in a car accident.

Photo courtesy of Maria Dominguez.

Dominguez said her mother didn't intend to keep the family in Texas after her father's death, but that Austin soon became their home and they joined the estimated 1.5 million undocumented immigrants in the state.

“The Champions of Change Award is allowing me to represent my community, a community that has a voice and a face but that chooses to live in the shadows because they are afraid to share their stories," she told Upworthy.

6. Yara Hidalgo, whose family brought her to California as a 1-year-old from Nayarit, a state in Western Mexico.

Photo courtesy of Yara Hidalgo.

Hidalgo knew from a young age that she wanted to be a teacher, but her experience as an undocumented high schooler — fearing deportation and unsure of her future — steeled her resolve.

"I believe that through education we can promote and be catalysts of progressive change," she said. "Some of our systems are broken and we need to fix them."

7. Rosario Quiroz Villarreal, whose mother brought her from the border state of Coahuila, Mexico, to Oakland, California, at age 7 so they could reunite with her father.

Photo courtesy of Rosario Quiroz Villarreal.

Throughout her life, educators supported her following her professional dreams. She wants to pay that back by guiding others in the same way.

“Growing up undocumented was challenging, given the times I've been rejected because of the lack of a Social Security number," she said. “This validates years of efforts and tells me my work matters."

8. Dinorah Flores Perez, who was 5 years old when her parents brought her from Mexico to the U.S.

Photo courtesy of The White House.

Flores Perez said she "detested" school as a child and chose her profession to make things better for other students.

"I remember feeling invisible, afraid, and insecure in my academic abilities," she said. "I seek to be a different teacher and see my students' limitations as a catapult to change their realities."

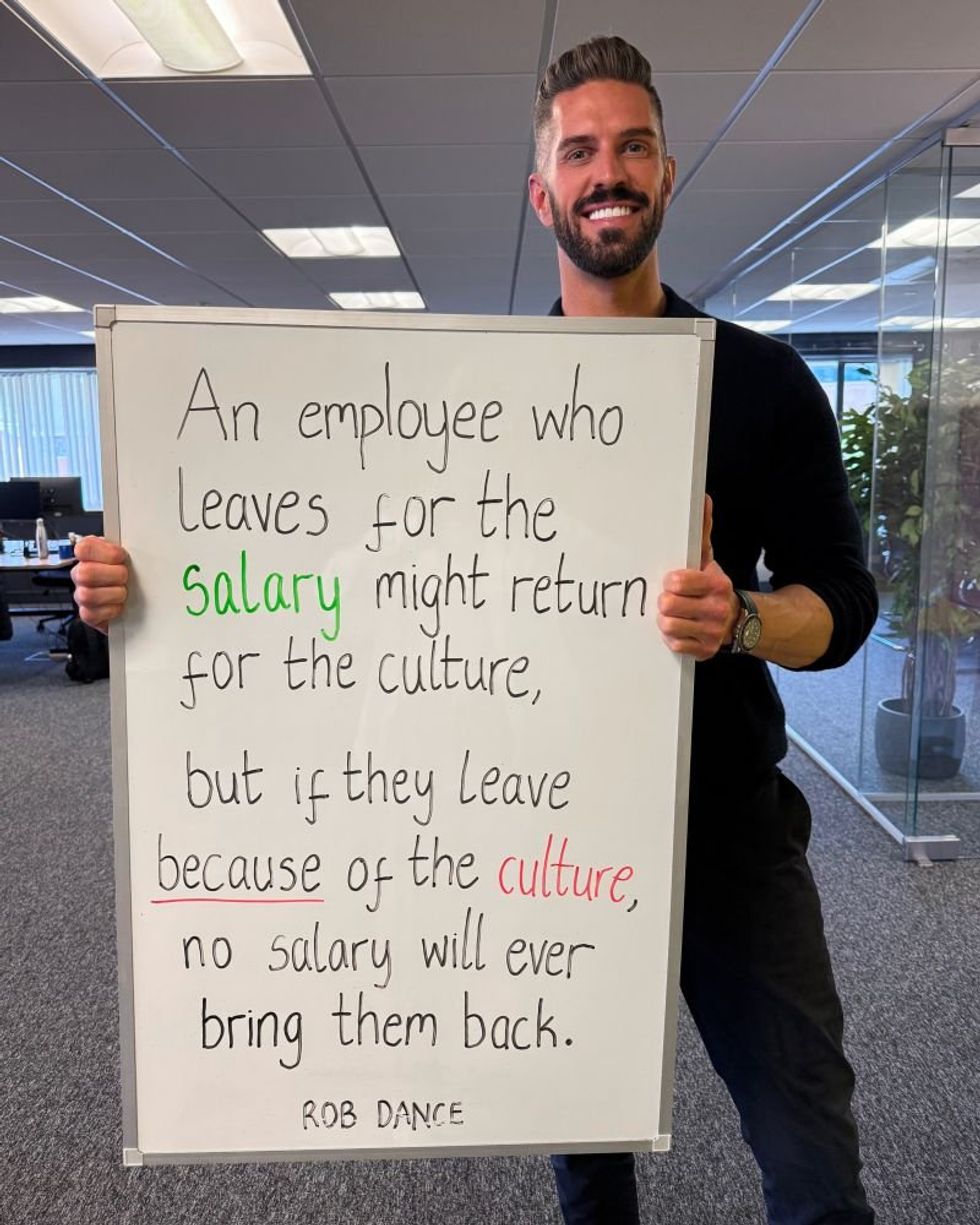

CEO Rob Dance holds up a whipe board with his culture philosophy.

CEO Rob Dance holds up a whipe board with his culture philosophy.  Courtesy of Kerry Hyde

Courtesy of Kerry Hyde Courtesy of Kerry Hyde

Courtesy of Kerry Hyde Courtesy of Kerry Hyde

Courtesy of Kerry Hyde Courtesy of Kerry Hyde

Courtesy of Kerry Hyde