Former FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover once said the most threatening thing about the Black Panthers was their free breakfast program for kids. Seriously.

That didn’t stop the FBI from keeping close tabs on people like Rodney Barnette, a founding member of the Compton chapter. A Vietnam veteran, he became disillusioned by the racism he experienced after returning home from the war. During his time organizing through the Panthers, he helped push the group's "radical" agenda that involved feeding hungry kids, protecting elderly in their neighborhoods, and providing black people easier access to health care and hospitals.

Eight different FBI agents followed Barnette for several years. They traded information with one another as they intimidated and gaslighted him, even going so far as to get him fired from his job at the post office. It was all in an attempt to demoralize and crush a movement they couldn’t control.

Rodney Barnette, circa 1968. All images by Sadie Barnette, used with permission.

The FBI had more than 500 pages of records on Barnette. Now, nearly five decades later, he and his family got to see those pages.

“We filed a request through the Freedom of Information Act, but it took about four years of back and forth writing letters before we actually got the file,” explains Sadie Barnette, Rodney’s daughter.

The loving father she’d known was a lifelong labor organizer with a passion for grassroots community building, a kindhearted man who built the first black-owned gay bar in San Francisco. She’d heard stories growing up about his involvement with the Black Panthers, but even he still had questions about that period of his own life — until the day that massive PDF document finally arrived.

“We were really just blown away by how much attention they paid,” Sadie explains. “They interviewed all of my dad’s employers. They interviewed his high school teachers and even the little old lady next door to where he grew up ... just so many resources they put into not just my dad, but anyone who was organizing with the Black Panthers and other groups at the time.”

Rodney’s name was included on the FBI's Administrative Index, or ADEX, which was essentially a terrorist watchlist at the time — a fact that Sadie calls sobering and terrifying. The agency even kept a detailed tree of his extended family, all of whom had been interrogated too.

Sadie as a baby, with her dad.

Then Sadie took those pages of her father’s life and turned them into art.

Sadie is an acclaimed visual artist whose work has been seen across the world. While the FBI files were obviously an important artifact for their family, she also knew they would make great fodder for a new project.

With her father’s blessing, Sadie combed through the files to find the most striking pages, and she found different ways to repurpose them — and the discordant story they told. She tagged some pages with pink and black spray paint like graffiti, while others were combined with her original artwork.

“There’s also these rhinestones that adorn some of the pages," she explains. “That was an act of love and an act of trying to to heal this really intense and violent surveillance that people were going through and also to memorialize some of the people who lost their lives during that time.”

Sadie didn’t just assert her family’s ownership and recontextualize the FBI records. She also juxtaposed them with her father’s own photographs of himself and of her as a child. “It’s really a chance to reclaim the narrative and paint a more real picture of my father,” she says.

The artwork become a physical exhibition called “Do Not Destroy” that was displayed at galleries in Oakland and New York, with another exhibit scheduled at University of California, Davis.

According to Sadie, nearly 400 people turned out at the opening in Oakland, which was part of a larger celebration of the 50th anniversary of the Black Panthers.

“It was a really intergenerational crowd,” she says. “People were there with their families, really reading through all the pages and investigating everything. I think because the Panthers were founded in Oakland, it’s a really personal history to so many people there. The courthouse where many Panthers had their trials was just two blocks from the museum, so it really felt like what our town is about.”

Some visitors even confessed to her in private about their own families' secret or shunned connections to the area’s history of black liberation and social progress. They said the artwork was inspiring them to find out if there were records on their parents too.

Sadie, at the exhibition's opening.

Sadie's artwork has also helped people realize this 50-year-old history is still frighteningly relevant.

“If you read the Ten-Point Program of the Black Panthers, it could’ve been written today. Nothing else is checked off the list, so to speak,” she says. “They were talking about systemic change."

The fact that the group is still remembered more as armed extremists than as community activists shows just how successful the FBI was in their campaign against people like Rodney.

Sadie also explains how the law used to fire her father from the post office — President Truman’s Executive Order 10450 — was originally put in place to keep LGBTQ people out of government work, not against black civil rights activists. “We have laws now, and people say, ‘Oh, that doesn’t affect me.’ But the same law can be used against you whenever the government decides that you’re the enemy.”

“With Donald Trump coming into office, a lot of people who may not have thought about it in this way before are realizing — hey, the government might not always be trying to protect the interests of the majority of the people,” she adds.

Rodney was in attendance at the opening of his daughter’s exhibition in Oakland.

He mingled with the other guests there, and stood and watched as they absorbed two contradicting accounts of his life from 50 years ago — and of course, admired his daughter’s beautiful handiwork. “It gave me a sense of freedom,” he said that night.

“I felt like, ‘Wow, I’m free now.’”

"Living a peaceful life, ironically, is really hard."

"Living a peaceful life, ironically, is really hard." A man in his 20s upset.via

A man in his 20s upset.via A couple saving money.via

A couple saving money.via A man and a woman have a fight.via

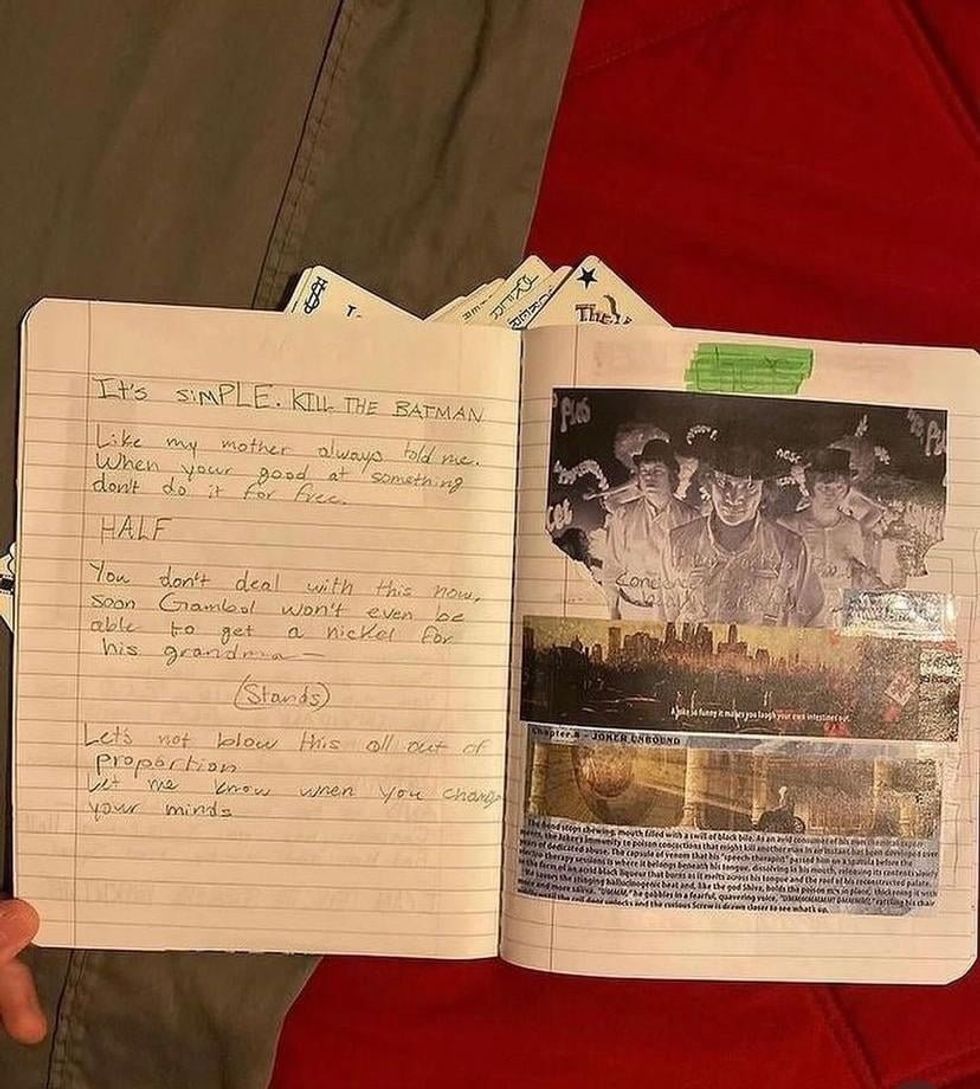

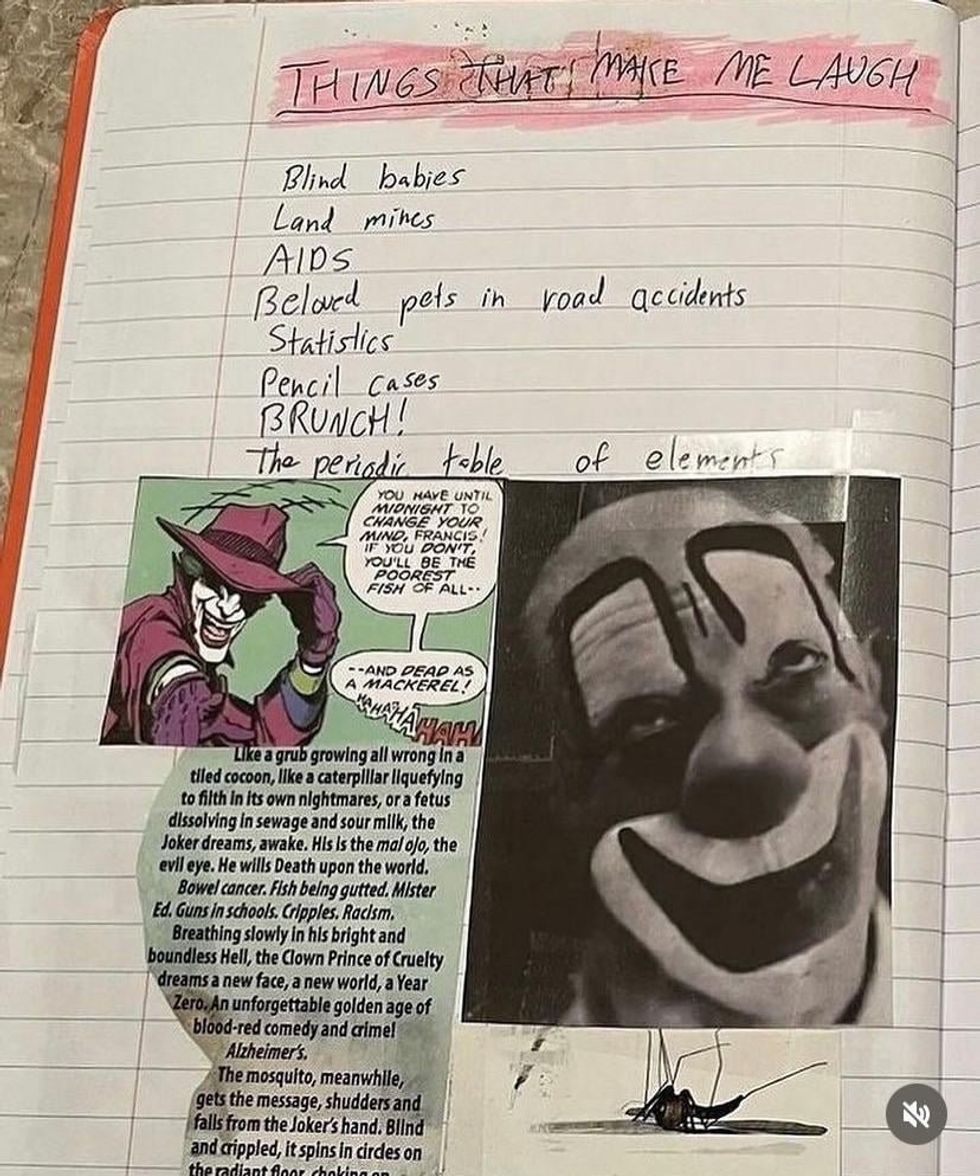

A man and a woman have a fight.via A page that beings with "It's simple. Kill the Batman."

A page that beings with "It's simple. Kill the Batman."  A page from Heath Ledger's diary while in prep for The Dark Knight

A page from Heath Ledger's diary while in prep for The Dark Knight