See incredible photos of a jail where inmates and abandoned animals find a second chance.

Mike Smith was out of jail for 10 days when he blacked out while drinking and was arrested alongside a busy street in Key West.

When he sobered up, he was back in jail. By his own admission, he was not surprised to be there. The blacking out had happened before.

"I’m done," Smith told himself. "If I don’t stop, I’m gonna spend the rest of my life in prison."

He has no recollection of being arrested, half a block off Duval Street.

This time, Smith knew he would have to do a small stint before he could get a spot in a substance abuse program.

In the interim, he signed up to be a trustee at the jail, working on a farm that for the last two decades has become a corner of Monroe County where abandoned, abused, confiscated, and donated animals from around the country have found refuge behind razor wire.

It's a place where a miniature horse named Bam Bam grazes his days away on a pasture as men in orange jumpsuits muck stalls and make sure water dishes are brimming.

Snowflake the alpaca is shown here as inmate Michael Smith visits with Arabella at the Monroe County Sheriff’s Office Animal Farm. All photos by Kim Raff, used with permission.

Inmate Orlando Gonzalez shows Boots the alligator to visitors during an open house day.

Curator Jeanne Selander holds Mo the sloth, the most well known animal at the farm.

Smith was amazed on his first day at the farm at the Monroe County Sheriff’s Office Stock Island Detention Center.

"I figured it’d be just a couple of pigs, maybe," he said. "I didn’t know there was gonna be snakes and lizards and alligators and everything else."

21 years ago, out on the busy road that runs alongside the jail, a flock of ducks was losing its battle with traffic. In response to their dwindling numbers, a fence was erected, a pond put in, and a few picnic tables where the guards took breaks. But the sanctuary didn’t stay small for long. And as word spread through the "coconut telegraph" — the unofficial gossip tree that spans the Florida Keys — the jail’s animal population began to increase and diversify. There was a lot of need, and it turned out the jail was beginning to look like the place to fill it.

Attention-hound Misty, a Moluccan cockatoo, repeatedly says “I love you” to visitors.

Gonzalez crouches down with Fat Albert, who escaped from his owner's home and was found roaming a hotel parking lot before being brought to the farm.

Gonzalez and Smith clean out animal pens.

Curator Jeanne Selander — or Farmer Jeanne as she’s known — runs the farm with the trustees.

For the inmates, it’s a way to make daily escapes from the jail in order to feed and clean the animals and build their trust. Selander came to the farm almost 10 years ago with a background in marine biology. She was working for the Key West Aquarium with veterinarian Dr. Doug Mader when the job opened up, and he encouraged her to apply. She had a love for animals, but she’d never stepped foot in a jail and was apprehensive about working alongside inmates.

Selander and Mo visit with a crowd during an open house at the farm.

After landing the job, Selander, still unsure, visited the site with Mader as he did his rounds. "I thought, 'What a neat little place' and how much more could be done with it. After I saw how the [previous] farmer interacted with the inmates and that it was a safe environment, I thought, 'Yeah, I could do this.'"

On Selander’s first day, 25 animals were roaming around. Most of them were farm animals, and most were of the petting-zoo variety.

Gonzalez shows Boots to visitors during an open house.

Bam Bam grazes in an enclosure. He is blind in one eye and was abandoned on the side of a canal with five other horses in Homestead, Florida.

Smith cradles Thumper, a flemish giant rabbit, as Fat Albert waddles over, looking for attention.

Today, Stock Island Detention Center is home to 150 animals, including Maggie, one of three sloths, and an alpaca named Snowflake.

Then there’s Peanut, a miniature horse found wandering in the Everglades after being abandoned by her owner.

The animals arrive at the farm through a network Selander builds with animal rescues throughout the country. The network focuses on finding homes for animals like Sherman, an African spurred tortoise, acquired during a raid on a crack house in Denver, Colorado. Or Ghost, a blind and elderly horse believed to be in his late 20s who arrived at the farm in 2008 as no more than skin and bone after being abandoned in a remote county of the state and who passed away last October.

Smith had known Ghost well. The horse would be spooked and stubborn at times. Some of the other inmates had a healthy fear of Ghost, but Smith made a connection.

"I just felt comfortable around him," he said. "And seeing that everyone else was uncomfortable around him, I knew that I had to do what I had to do to make sure he was taken care of right and not neglected. Doing something good when I was in a pretty bad situation myself, it really gave me peace," he said.

Smith brushes Ghost, a blind horse that frightens easily which has taught people who handle him to be patient, gentle, and build trust.

Some of the inmates "try to be the big burly guys with the attitude," Selander said. "And that always used to move me whenever I’d see them talking to the blind horse because that’s a bond they’re forming with an animal that needs them."

Twice a month, the farm invites the public in to fawn over the animals. Selander’s outreach into the community and the reputation of the farm means it’s not unusual for bi-monthly Sunday open houses to draw in as many as 200 people. Many of them are greeted by Mo the sloth, who is regularly an ornament cradled in Selander’s arms as guests arrive.

"Everyone thinks he is hugging me, but really he just thinks I’m a tree," Selander said.

Signs directing visitors to the animal farm hang along the Monroe County Detention Center’s fence.

It’s the community support that allows for the farm to continue its work. The farm is completely funded by donations. No tax dollars go to fund the project.

"If I ever need anything, the community really steps up to help," said Selander.

Along with the inmates.

"A lot of the inmates maybe have never had anybody that cared about them," she said. "And to see that the animals need them ... it means something to them. And they really take good care of them and I have some of them say, 'You’re in jail just like me.'"

Gonzalez and Smith move animals from their pens to the courtyard to graze.

Today, Smith is finishing up treatment and has found work.

He is sober. But he fondly remembers his time on the farm with Misty the Moluccan cockatoo that he snuck orange slices to. The one that followed him around the farm cooing, "I love you."

"It kept me focused," Smith said. "Spiritually, it helped me a lot. I definitely won’t forget it; that’s for sure."

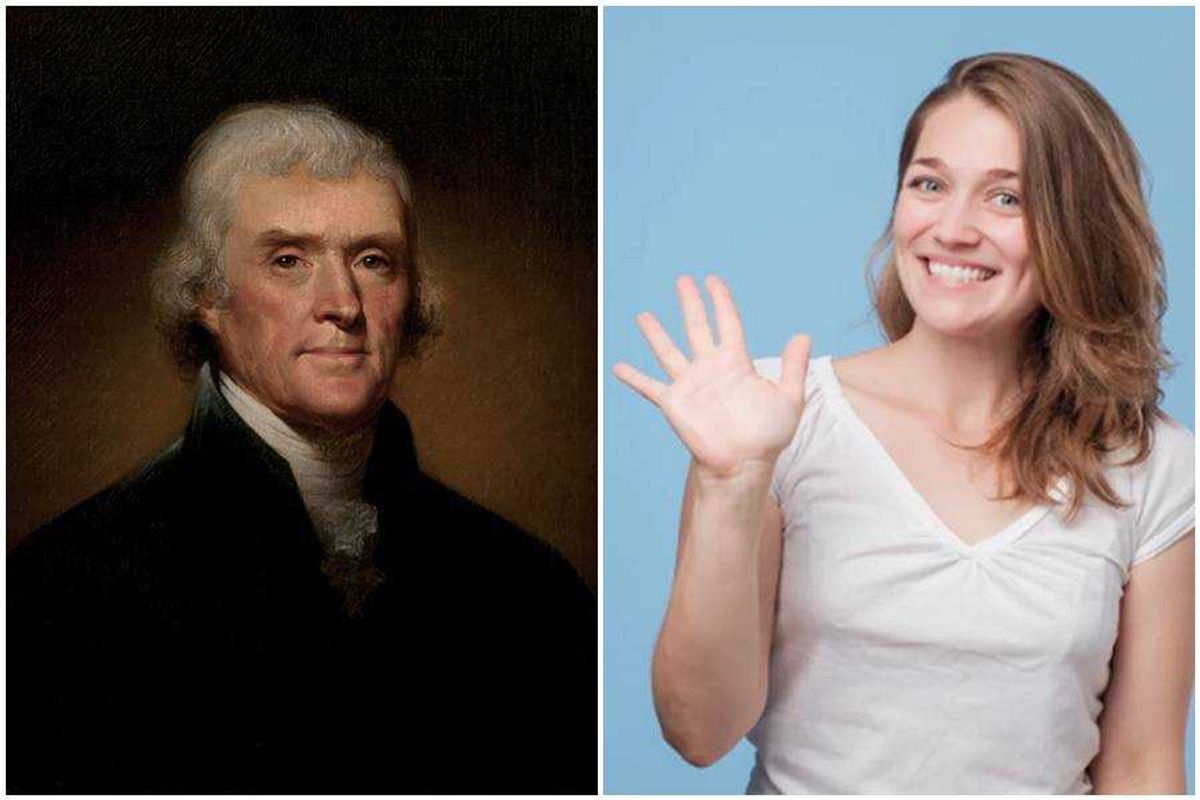

Thomas Jefferson's Monticello.via

Thomas Jefferson's Monticello.via  The Jefferson Memorial in Washington, D.C.via Joe Ravi/Wikimedia Commons

The Jefferson Memorial in Washington, D.C.via Joe Ravi/Wikimedia Commons

Indoor cats can enjoy the outdoors safely with a harness and leash.

Indoor cats can enjoy the outdoors safely with a harness and leash.

Do any of us still make sourdough?

Do any of us still make sourdough?  A fused glass bowl.

A fused glass bowl.  An example of aquascaping.

An example of aquascaping.  Whittled Halloween figures.

Whittled Halloween figures.  A water color painted bookmark.

A water color painted bookmark.  A cross-stitched pattern of a goddess-like woman.

A cross-stitched pattern of a goddess-like woman.  Latte art.

Latte art. A handmade wood cabinet.

A handmade wood cabinet. A watercolor butterfly.

A watercolor butterfly. An oil portrait of a baby.

An oil portrait of a baby.  Pressed four leaf clovers.

Pressed four leaf clovers.  A clay pumpkin.

A clay pumpkin.

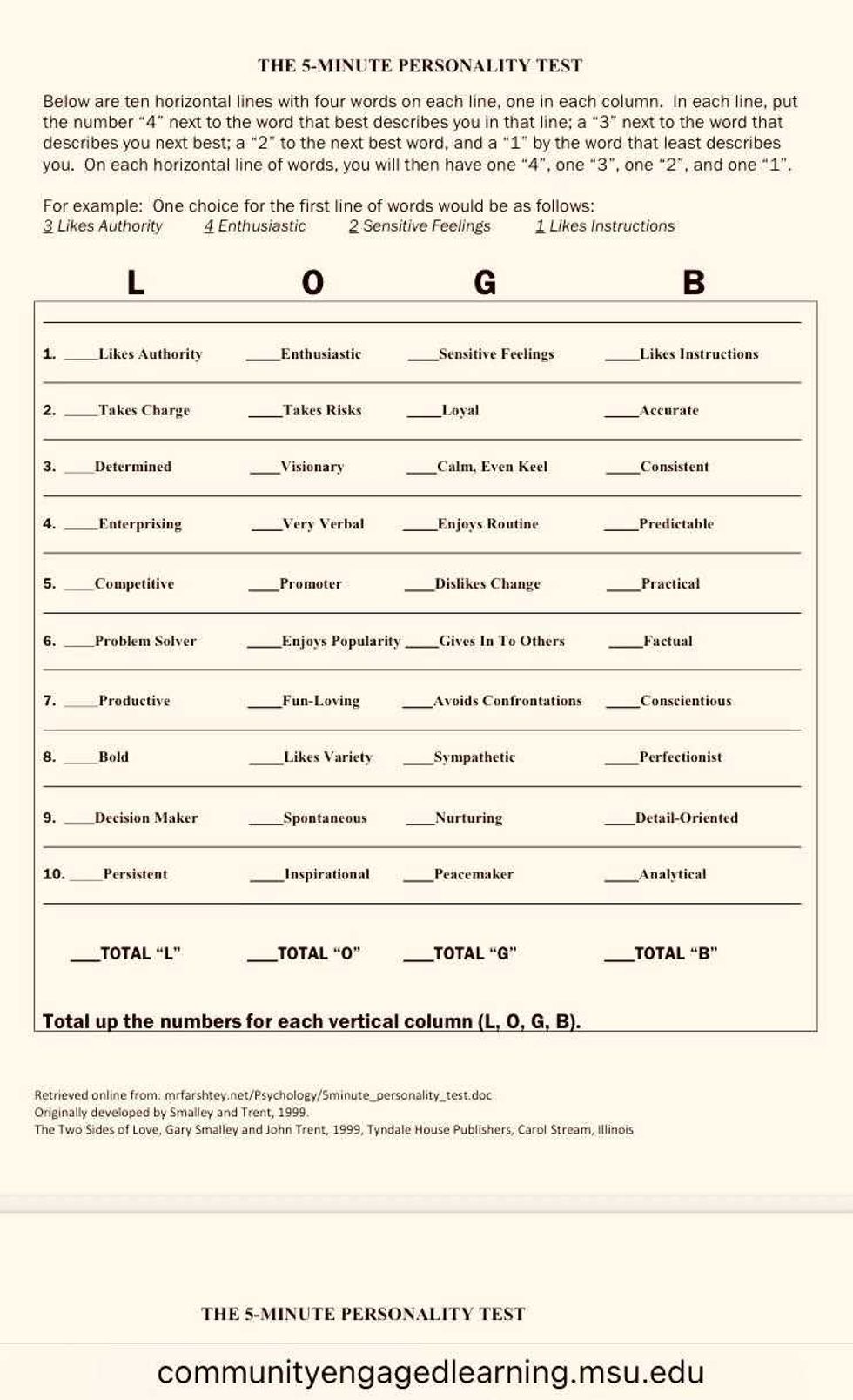

Gary Smalley and John Trent's personality test

Gary Smalley and John Trent's personality test A lion roams.

A lion roams.  An otter is surprised.

An otter is surprised.  Beaver enjoying a snack.

Beaver enjoying a snack.  Golden Retriever adorably looks up.

Golden Retriever adorably looks up.